Childhood trauma is common1 and can have profound consequences throughout a person’s life (Box 1).2–4 Although the total prevalence of childhood mistreatment is difficult to measure, it may be as high as 28%.5 Trauma is more common in women2 and in population groups that have a higher incidence of cumulative or intergenerational trauma, such as refugees or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.6,7 The impact of childhood abuse is significant, comprising approximately 2% of the total disease burden.2 Cumulative trauma, where there are multiple adverse childhood experiences, leads to poorer health outcomes.8

| Box 1. What is childhood trauma, and how common is it? |

|

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) is the term used to describe all types of abuse, neglect, and other potentially traumatic experiences that occur to people under the age of 18 years.

ACEs have been linked to risky health behaviours, chronic health conditions, low life potential and early death.

As the number of ACEs increases, so does the risk for these outcomes. The presence of ACEs does not mean that a child will experience poor outcomes.

The definition of child abuse and neglect can be found on the Centers for Disease Control website (www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/CM_Surveillance-a.pdf).

The definition of and diagnostic requirements for complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can be found on the International Classification of Diseases website (https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/585833559).

Note that complex PTSD is a new diagnosis in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision, and was endorsed by the member nations of the World Health Organization in May 2019, due to come into effect from 1 January 2022.

Prevalence of childhood trauma

A systematic review of Australian research estimates prevalence rates of childhood sexual abuse are approximately 8.6%, physical abuse 8.9%, emotional abuse 8.7% and childhood neglect 2.4%.2

Multiple forms of trauma can occur, and cumulative trauma is more damaging than single-episode trauma.3 Trauma may or may not be deliberate: a young child with leukaemia may experience hospitalisations as deeply traumatic despite no intent to harm on the part of the caregivers. Not all trauma is mistreatment.

|

General practice management of adult survivors of childhood trauma

Adult survivors of childhood abuse pose a number of challenges for general practitioners (GPs): the diagnosis of their medical and psychiatric illnesses is complex;9 the therapeutic relationship can be both delicate and critical to recovery;10 and the treatments available are varied, often expensive and frequently inaccessible.11,12 Medicare Benefits Schedule rebates favour short consultations, and this makes mental healthcare in general practice financially difficult.13 Given the prevalence of childhood trauma, many GPs will have their own trauma histories, which complicates the therapeutic relationship.14 Vicarious trauma is common,9 and GPs frequently feel unsupported and uncertain about how best to manage the distress that can be associated with trauma.15 Many GPs may still be developing their capacity to ‘sit with uncertainty’ and to support a patient in distress without attempting to ‘fix the problem’.16 The combination of these factors means that it may be difficult to manage such a sensitive and traumatic issue appropriately.

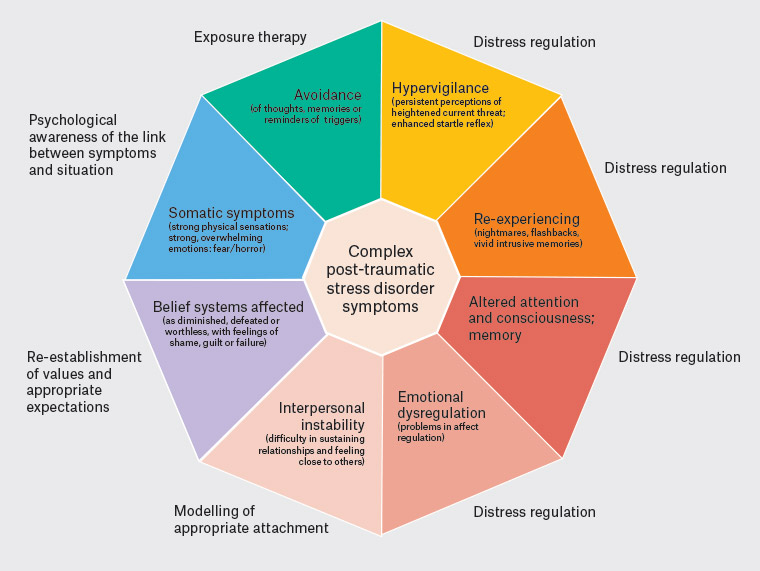

It can be challenging for survivors of childhood trauma to directly disclose; it may take up to decades for some to do so, if they do so at all.17 Instead, patients may present with conscious or subconscious manifestations of distress: somatic, psychiatric, psychological or social. These consultations require listening to both the overt distress and the ‘underneath story’ of trauma and recovery. The following are typical symptoms for adult survivors of childhood trauma (Table 1). Figure 1 summarises the features of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), one diagnostic formulation for the consequences of childhood abuse.18,19

| Table 1. Common symptomatology seen in survivors of childhood trauma linked to intervention |

| Symptom type |

Common symptomatology seen in survivors of childhood trauma |

Targeted intervention |

| Somatic symptoms |

Medically unexplained symptoms

Syndromes such as irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia

Chronic pain

Consequences of maladaptive coping (eg substance abuse, eating disorders)

May be associated with strong emotional states |

Validation of the patient’s physical distress and appropriate investigation

Psychoeducation regarding the psychological awareness of the link between symptoms and situation |

| Emotional dysregulation |

Irritability and chronic hyperarousal

Recurrent or chronic suicidal ideation

Self-harm

Maladaptive coping strategies (eg addictions, eating disorders) |

Distress regulation*

Psychoeducation regarding the psychological awareness of the link between distress and situation |

| Interpersonal instability |

Re-enacting unhelpful relationships from the past (eg becoming abusive themselves, or partnering with an abusive partner)

Poor parenting skills |

Modelling of appropriate attachment

Offering a stable and supportive therapeutic relationship |

| Avoidance |

Gaps in the history-taking or the story

Diversion or distraction associated with a specific theme

Behaviours associated with avoidance. These may include substance use, eating disorders or disruptive behaviours. Avoidant behaviours may also be traditionally considered as ‘positive’ behaviours until they become maladaptive. An example could include distraction into work rather than addressing the issues most triggering the emotional distress. |

Validation and acknowledgement of the patient’s distress and what they have been able to achieve

Supportive therapy to build on other resiliences

Exposure therapy, once the patient is ready

Note: If a person is using avoidance as a coping mechanism, they may be feeling too overwhelmed at this point of time. Go slow. Engaging the patient may require identification of what they are avoiding; drawing links between the distress and current management style (avoidance); and exploration of alternatives. This should be patient centred, or otherwise risks alienating the patient. |

| Re-experiencing and dissociation |

Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, including nightmares, flashbacks and re-experiencing

Flashbacks may be predominantly emotional (ie feeling acutely distressed, anxious or fearful for no apparent reason and with no obvious narrative)

Dissociation, where survivors lose track of time and place, or have an intense experience of depersonalisation or derealisation |

Distress regulation

Exposure therapy |

| Disorders of memory |

Fragmented memories from childhood |

Psychoeducation

Distress regulation |

| Shame |

Poor sense of self, including beliefs that they are fundamentally defective, toxic or worthless |

Establishment of values and appropriate

goal setting† |

*Further ways to manage distress regulation are considered in Box 2. Asking difficult questions – Identifying a person’s strengths and supports.

†Achieving a sense of purpose or meaning is an important aspect of self-actualisation. This concept is known by various names in different forms of psychotherapy. For example, in cognitive behavioural therapy, it can be called ‘schema therapy’. In acceptance and commitment therapy, it can be the ‘values’ and ‘goal setting’ arms of therapy. The goal of psychodynamic therapy is for the patient come to an understanding of their sense of purpose or meaning through exploration of their self-belief within a consistent, respectful and empathic therapeutic relationship. Self-actualisation and changing belief settings may only be possible once other needs, such as safety and security, are met. |

Figure 1. A model of complex post-traumatic stress disorder with potential general practice interventions18,19 Click here to enlarge

Adapted from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies guidelines and the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision

Somatic symptoms

There is increasing understanding of the neurobiological changes apparent in survivors of childhood abuse,20–22 and there is also increasing understanding of the somatic consequences of chronic stress.23 For these reasons, it is important to explore trauma histories in patients with complex and chronic illness, particularly when illnesses are ill-defined or contain mixed emotional and physical symptoms.21,24,25 Presentations of somatic symptoms are outlined in Table 1.

Emotional dysregulation

Survivors may find it more difficult to regulate their emotions when they are under stress26 or re-experiencing a sense of powerlessness. Because of the intensity of their emotional experience, and the poor sense of self that often follows childhood trauma, these patients may have recurrent or chronic suicidal ideation and self-harm.7,21 Children who grow up in abusive families often have little opportunity to learn healthy emotional coping skills and may learn to manage strong emotions in unhelpful ways (Box 2).

| Box 2. Asking difficult questions |

As a result of the disordered memory associated with childhood trauma, it can be challenging to ask appropriate questions. Many adults who have experienced severe trauma will not remember or recognise their childhood as abusive.

Asking difficult questions about adverse childhood experiences

Useful questions include:

‘Was your home a safe and secure place?’

‘What were you like as a young child?’ (Children who have been abused often have a highly negative self-image of themselves, such as ‘My mother said I was born angry’ or ‘I was ugly and everyone said I was stupid’.)

‘Were you asked to keep any secrets as a child?’

‘What happened when you were punished as a child?’

‘Did anything happen to you in childhood that hurt you?’

‘Did anything happen around you that made you feel unsafe?’

‘Was there someone you could turn to when life was difficult?’

Identifying a person’s strengths and supports

What coping strategies have they found helpful in the past?

If the coping strategies are maladaptive (eg substance abuse, food restriction/purging, self-harm or other risky behaviour), then explore further until a coping strategy that is less maladaptive has been identified.

Potential coping strategies include lifestyle factors (sleep, exercise, diet), distraction, connection with others, pursuing meaning and purpose in life (eg meaningful work, volunteering, advocacy, caring for others), creative pursuits and various forms of therapy.

Whom have they found helpful in the past?

Troubleshooting involves the following types of questions:

At times when support can be variable, what factors have made the support more helpful?

At times when there are limited personal supports, what professional supports have been helpful in the past?

If the patient does not think the supports (personal and/or professional) have been helpful in the past, what type of support do they need now? The aim is to help them construct a list that is specific and achievable. This may take some time; trust will develop slowly.

Identifying a person’s strengths and supports can assist the person with emotional dysregulation to identify coping strategies that are more helpful. |

Interpersonal instability

Interpersonal difficulties can arise as a result of disordered attachment and modelling of relationships.7,27 Symptoms may be more predominant at important life events such as marriage, pregnancy and childbirth. When abuse occurs within the family, or in another trusted group of adults (eg school, religious institution, sporting club), the trauma is compounded by betrayal of trust.28,29 In betrayal trauma, symptoms are more likely to be severe, and survivors often lose their capacity to detect unsafe behaviours into adulthood.30 For this reason, they are more likely to stay in unsafe relationships.

Disorders of memory

There is evidence that children who experience trauma have fragmentation of their memories of childhood.31 Disorders of memory can make understanding and validating trauma extremely difficult. When taking a history, it is important to respect this fragmentation. The goal is not to reconstruct the facts but to understand and manage the consequences. Most survivors will be able to articulate that childhood was distressing, even if they cannot give a clear narrative of their childhood experience. This is most common in patients who experienced trauma at a very young age (ie younger than five years of age).32 It is more likely that patients will be unable to articulate their distress the younger they were when exposed, and the more prolonged and persistent their experience, particularly if their experience occurred in the absence of other positive childhood experiences and attachment figures. Dissociation can still occur even if the event occurs after adolescence, especially the more significant the intrusiveness of the event, and if there is a pronounced experience of helplessness.

Re-experiencing and dissociation

PTSD is common in patients with a history of childhood trauma. However, when trauma occurs in childhood, the flashbacks may well be experienced as a flood of emotion, disconnected from the narrative in which the trauma originally arose.27 This is partly due to fragmentation of memory.31,33 As a result, survivors may struggle to identify triggers, and so may misinterpret re-experiencing as panic attacks or hallucinations. Re-experiencing (Table 1) may be predominantly emotional (feeling acutely distressed, anxious or fearful for no apparent reason and with no obvious narrative) or somatic (medically unexplained symptoms; syndromes such as irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia; chronic pain; consequences of maladaptive coping such as substance abuse, eating disorders). Avoidance of the feelings or sensations may create a sense of being disembodied or distant from the experience (dissociation). Many people will find this experience difficult to talk about or describe, so it will require careful supportive questioning (Box 2) to elicit these experiences if this information is crucial to recovery.

Avoidance

Adults may also carry coping strategies that were helpful in childhood into adulthood, including avoidance or the tendency to dissociate during stress.26,34 Intense somatic and emotional symptoms and a sense of loss of control over these sensations are understandably feelings that the person often seeks to avoid. This can become even more confusing when there is cognitive impairment or triggers are perceived to be unpredictable. At an unconscious level, the person may not be able to identify the emotional distress occuring and may report dissociative symptoms. There is high comorbidity with complex PTSD and substance use, and there is evidence for managing the complex PTSD and substance use concurrently.35

The person may seek to avoid the unpleasant experiences by rerouting their sense of chaos to something they feel they can control; this can give rise to unhelpful behaviours such as comorbid eating disorders.36 Alternatively, they may redirect to productive actions and be extremely successful in other aspects of life. Avoidance may be the only defence the person has developed to cope with the unpleasant experiences they have had. Box 2 explores how to ask about this and build on alternative ways of coping.

Shame

One of the most painful symptoms of early childhood trauma is a pervasive sense of shame.27 A healthy sense of self is established early in childhood and developed through constant reinforcement by significant attachment figures in a child’s life. If a child is abused at a young age, they tend to believe they deserve it. This may be reinforced if the abuser implies the trauma is the child’s fault or if the child is not believed by other family members. This pervasive sense of shame can be difficult to shift; it is not unusual for a survivor to be valued, successful and respected but still carry a deep burden of shame.

Diagnosis

Given the complexity of symptomatology experienced by survivors, many will have acquired a raft of diagnoses, including depression, anxiety, panic disorder, psychosis and borderline personality disorder. This is confusing for patients and their GPs. However, symptoms can be clustered together to form a unifying diagnosis of complex PTSD, now listed in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11).19 This type of PTSD is ‘complex’ because of the developmental consequences of early trauma; a child is developing their core sense of self, learned behaviour, expectations of relationships and neurological system, and all this is disrupted by trauma.

It is important to note the crossover of borderline personality disorder and complex PTSD. Many patients with complex PTSD will have previously been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and experienced the stigma associated.37 There is increasing awareness of the role of trauma underlying the pathophysiology of symptoms for those people, and thus the change to the diagnosis of complex PTSD. There have also been marked changes in the classification of personality disorder in ICD-11, but not yet in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, from categorical to dimensional descriptors. ICD-11 now focuses on the severity of personality disorder rather than on the type of personality dysfunction.38 This can then be further classified by traits. Consequently, a person with complex PTSD may have severe personality disorder or no personality disorder, where they have persistent feelings of shame or poor self-worth that do not affect functioning.

Managing complex PTSD: The story underneath

Disclosure of the trauma story underneath is more likely if the consultation is undertaken in an empathic, non-judgemental style.39 However, trauma can also affect consultation dynamics. There may be normalisation in groups where complex PTSD is prevalent, and other organisational barriers such as language and access to services. In people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander background, previous stigmatisation and trauma by people in authority may negatively affect trust within the clinician relationship. This becomes more significant when issues of child safety and potential removal are raised.40 Many of these patients struggle with emotional dysregulation and poor interpersonal skills, so they can be defensive, angry and even abusive themselves. This can trigger a strong emotional reaction in their clinicians.41 For self-care, and for the benefit of the therapeutic relationship, it is important that health practitioners are mindful of and carefully manage their own emotional responses.

Recovery requires rehabilitation of the sense of self. This involves not only sharing an understanding of how trauma affects the mind and body, but also the experience of empathy, respect, validation and compassion: what Rogers called ‘unconditional positive regard’.42 GPs are uniquely placed to provide this reparative relationship, demonstrating to patients that they are worthy of time, respect and empathy.

Time is a significant barrier in general practice, and GPs may consciously or unconsciously avoid starting the conversation for fear of the ‘Pandora’s box’:43,44 opening up trauma they feel unable to manage. Clinicians may also carry assumptions about their patients, particularly if the patient seems to be high functioning. Patients can have significant psychological disability and still appear quite high functioning: some patients manage their trauma by overachieving in the workplace.

When to intervene

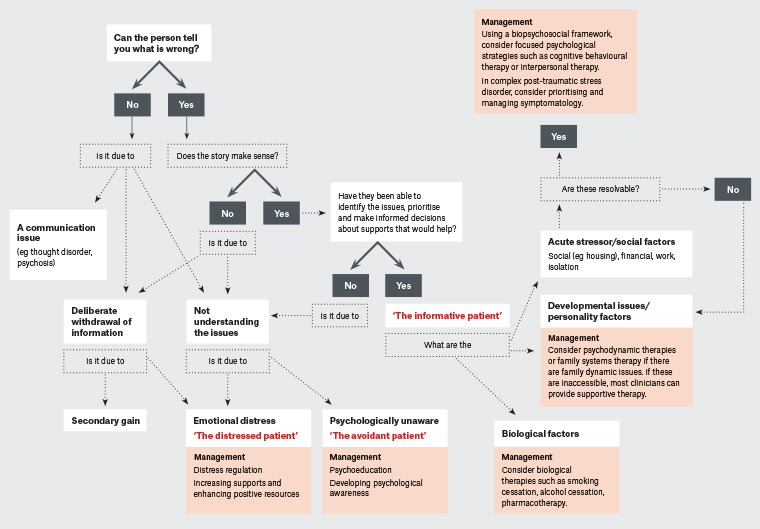

Intervention is helpful if there is functional impairment or significant distress and the patient is ready to address this. Common presentations that may guide intervention styles are summarised in Box 3.

| Box 3. Common presentations of complex post-traumatic stress disorder that inform intervention style |

The informative patient

- The informative patient may be more psychologically aware of the link between their symptomatology and complex post-traumatic stress disorder. They may be ‘matter of fact’ and report in explicit detail.

- There is a risk of ‘emotional backlash’, where the retelling of the story may

be re-traumatising.

- The focus of intervention is prioritisation of issues to allow this to guide timeframes for each intervention.

The distressed patient

- Maladaptive coping styles in response to the distress are predominant.

- The aim of treatment is for the patient to establish the link between their trauma and symptoms. It is critical that the health practitioner acknowledges the trauma and validates the patient’s experience.

- The focus of intervention is on emotional regulation and distress tolerance.

The avoidant patient

- The avoidant patient may present with unrelated matters, often frequently. Queries are often met with topic change. In this situation, it is important for the general practitioner to progress slowly.

- It is important for practitioners to identify that the patient is distressed by something and offer them support. Avoidant patients can be understood as ‘emotional pre-contemplators’: they may not be ready to address their trauma with a health practitioner, and need gentle, persistent support to feel safe to disclose.

- The focus of intervention is on psychological awareness and distress tolerance.

Figure 2 considers a stepwise approach that outlines how these presentations may inform management. |

Therapies used for complex PTSD

Psychotherapies for the management of complex PTSD that are supported by evidence include modified cognitive behavioural therapies such as dialectical behaviour therapy and some psychodynamic therapies (Figure 2).45 For many patients with complex PTSD, particularly in rural and remote contexts, the GP may provide the only supportive relationship they have.46 GPs can enhance positive supports and promote resilience47 while providing a long-term, empathic therapeutic relationship. Supportive therapies include art, yoga, exercise, community engagement, music and behavioural activation.

Figure 2. Roadmap to recovery: A flowchart for the management of adult survivors of childhood trauma. Click here to enlarge

Medications such as selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, antipsychotics and sedatives can target distress regulation. People experiencing significant psychological distress often request pharmacotherapy, but the greater the distress, the more likely there may be anxiety associated with the medication and its reported side effects. Therefore, patients may need considerable support when initiating or changing medication.

How to select the right therapy

It can seem overwhelming to manage patients with PTSD when multiple issues are present and when management options are uncertain. Focusing therapy on the predominant issues presenting at the time engages the person in their own care plan (Figure 1). Needs can constantly change. It is better to foster empowerment through small successes than overwhelm with failures. Comorbidity is common and should be considered in the therapy paradigm.

Therapy should be guided by the individual’s values, capacity and needs. When there are multiple issues occurring, a model such as Maslow’s hierarchy can help with prioritisation. Physiological needs are more critical than self-actualisation, so addressing core beliefs and values may need to be delayed until the patient has safe shelter and food security. Targeted management options are discussed in Figures 1 and 2.

Recovery includes addressing social and environmental circumstances, as well as fostering connectedness, self-compassion and a sense of purpose or meaning. A recovery journey may result in a greater number of adaptive strategies, but it may also include poor choices or unhealthy relationships. As part of risk management, it is appropriate to voice when unsafe behaviours occur. However, if the patient has capacity to choose, then decisions are ultimately their own. By being open and non-judgemental, GPs can encourage patients to be more open to reconsidering their choices in the future.

Implications for practice

There is increasing awareness of the role of GPs in the care of a person who has experienced childhood adversity. GPs can be effective and facilitate recovery-orientated, trauma-focused care, even when local services are limited.

Key principles include listening and engaging to understand why the person is presenting in this way and approaching care in a targeted and collaborative approach. This can alleviate emotional distress for the person, GP and care team.

To ensure long-standing continuity of care and ongoing therapeutic alliance, the clinician must also ensure that their own care needs are met, even while caring for others. While it can be rewarding working with survivors of trauma towards recovery, it can also be complex and challenging, especially in a practice with limited other supports and services. Much of this article has discussed factors within the GP–patient interaction that can enhance the recovery journey and therapeutic relationship. The organisational team that surrounds the care team, including the interactions and support of the non-clinical team, will also have an impact on the recovery journey. The non-clinical (and clinical) support team may benefit from additional guidance relating to the principles discussed in this article. Scheduling more frequent regular appointments of appropriate duration, particularly during crisis periods, may allow the patient to hold their emotional distress until the next scheduled appointment, reducing the frequency of ‘unanticipated crisis’. There will be times when personal resources will be stretched. At this time, support is available through doctors’ health and advisory services, which are available in each Australian state and territory and outlined in the Resources section of this article. As part of ongoing personal care, it is important that GPs have the space and time for activities that foster wellbeing, including personal reflection. This can include mentor or peer support groups, formal or informal. This may need to be deliberately scheduled or structured, especially as resources become stretched and there are greater competing demands. Balint groups are peer support groups that focus on the clinical relationship.48 They can be run locally or by teleconference.

GPs can make a difference in the recovery journeys of patients with complex PTSD. Improved understanding and facilitation of the recovery journey can decrease the emotional distress of all involved in that recovery journey, including the patient and healthcare provider.

Resources

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Abuse and violence: Working with our patients in general practice. 4th edn. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2014. Available at www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/white-book

- Marel C, Mills KL, Kingston R, et al. Guidelines on the management of co-occurring alcohol and other drug and mental health conditions in alcohol and other drug treatment settings. 2nd edn. Sydney: Centre of Research Excellence in Mental Health and Substance Use, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales, 2016. Available at https://extranet.who.int/ncdccs/Data/AUS_B9_Comorbidity-Guidelines-2016.pdf

- Blue Knot Foundation: National Centre for Complex Trauma. Available at www.blueknot.org.au

- Project Air: A Personality Disorders Strategy. Strategy for personality disorders. Wollongong, NSW: University of Wollongong, 2019. Available at www.projectairstrategy.org

- 1800RESPECT: National Sexual Assault, Domestic Family Violence Counselling Service. Greenway, ACT: DSS, 2016. Available at www.1800Respect.org.au

- Balint Society of Australia & New Zealand. Peer support groups can be run locally or by teleconference. Available at www.balintaustralianewzealand.org

- DRS4DRS. Doctors’ health and advisory services exist for doctors and medical students, available in each Australian state and territory. Barton, ACT: Doctors’ Health Services, 2019. Available at www.drs4drs.com.au/getting-help

- Australasian Doctors’ Health Network. St Leonards, NSW: Doctors Health Advisory Service, 2020. Available at www.adhn.org.au