An ageing population with a higher prevalence of multimorbid chronic conditions is placing pressure on general practice to provide optimal care to older Australians.1 Yet general practice registrars see fewer older patients with chronic disease than established general practitioners (GPs).2,3 Furthermore, registrars have fewer opportunities to be involved in the continuity of care needed for older patients with chronic disease.4

The Registrars’ Clinical Encounters in Training (ReCEnT) project5 demonstrated that general practice registrars have relatively limited exposure to older people, particularly older peple with chronic conditions.2 Moreover, continuity of care in Australian registrars’ training experience is modest,4 yet older patients are willing to see a general practice registrar,6 especially when given relevant information.7 The challenge is how to increase exposure to aged care and chronic conditions by general practice registrars and, at the same time, maintain continuity of care by the patient’s regular GP. Models for registrars’ management of complex problems are needed to address gaps in aged care management and teaching in general practice.8

The data in this article are drawn from a qualitative study that explored approaches to in-practice aged care teaching and exposure by registrars to older patients in general practice. This article presents findings from interviews and focus groups with supervisors and registrars regarding their experiences of registrars’ exposure to, engagement with, and continuity of care for older patients with chronic disease, with the goal of eliciting ideas for shared patient care models.

Methods

We used purposive sampling of general practice supervisors and registrars in Tasmania to explore supervisors’ and registrars’ views across the state and at regional levels. We chose an interpretivist perspective as an appropriate theoretical position to understand and explain these views.9 We chose interviews and focus groups as relevant methods. One-on-one interviews are appropriate for participants who may not be comfortable expressing their views in a group setting. Focus groups allow participants to generate and develop ideas that might not emerge from single viewpoints expressed in one-on-one interviews. Additionally, participants who are reluctant to be interviewed on their own or feel they do not have much to say can be more comfortable in a group setting.10

We did not set a particular age range but explained in the interviews/focus groups that we were interested in the ‘older patient with chronic disease(s)’. This was clarified in the focus groups as generally ≥75 years, although ≥65 years is considered ‘older’ when chronic conditions/multimorbidity is present.

Interview/focus group schedules were derived from the literature and from the experience of the research team. Box 1 details the interview schedule for supervisors. All interviews were conducted by the lead author (MB – an experienced health services researcher). Focus groups were facilitated by two authors (MB – a male researcher, and FS – a female registrar). All interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

| Box 1. Interview/focus group schedule for supervisors |

What is your practice’s approach to aged care in practice teaching?

How are registrars in your practice exposed to aged care patients and chronic disease management in older people?

- What does your practice understand are the roles/needs of the registrar?

- How do the reception staff and nursing staff understand their roles? In what ways do they explain to patients the role of a registrar?

- How do older patients respond to being seen by a registrar?

- What do you consider to be the barriers to engaging registrars in care of older patients?

Tell us about the amount of exposure that registrars you supervise have to older patients with chronic disease.

How do you think the amount of exposure to aged care patients compares with vocationally registered general practitioners (GPs)? Do you think the amount of exposure should be more or less or is about right?

If older people are seen by a registrar, how is the quality (and continuity) of care maintained? To what extent do registrars engage with management or defer decisions until the patient sees the supervisor/other senior GP?

In what ways have you been able to gauge the registrars’ actions in regard to their engagement with older patients? (Prompt: based on ReCEnT? Or from elsewhere, your assessment of what you read in the consultation notes, or what patients tell you?)

Discussion of the challenges, risks and benefits relating to aged care teaching and aged care exposure for GP registrars.

- How can we maintain relational and informational continuity with older patients’ ‘regular’ GPs and still ensure that registrars are adequately engaged in treating older patients?

|

Analysis

An interpretive thematic analysis of the interviews/focus groups was undertaken, focusing on the phenomenon of interest,10 which in this case was the experiences of supervisors and registrars of exposure to older patients with chronic disease. Transcripts were independently coded by two researchers (MB, and RK – a male GP and medical educator) who then met to discuss their analyses and interpretations. Negative cases were sought and examined particularly closely.11 The themes were refined by three researchers (MB, FS, and EH – a female health sociologist). The other researchers (RK, PM and AB – two experienced male GP academics) provided feedback on this analysis. The final set of themes was organised by group (supervisors/registrars) to allow the themes to be compared and contrasted.11 Researchers discussed the findings, considered alternative explanations, and used constant monitoring of analysis and interpretation to ensure rigour.

Research team and reflexivity

An interprofessional team with diverse professional backgrounds and experiences conducted the study. At all stages a process of reflexivity was followed to minimise potential bias in the conduct of the study.12 For example, a non-clinical researcher conducted the interviews, and worked with a medical educator, a registrar and health sociologist on the analysis, with two experienced GP academics providing external checking on the interpretations. In this way, the team were able to bracket any assumptions.10

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the Tasmania Social Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (reference: H0016418). Supervisors and registrars were reimbursed for their time.

Results

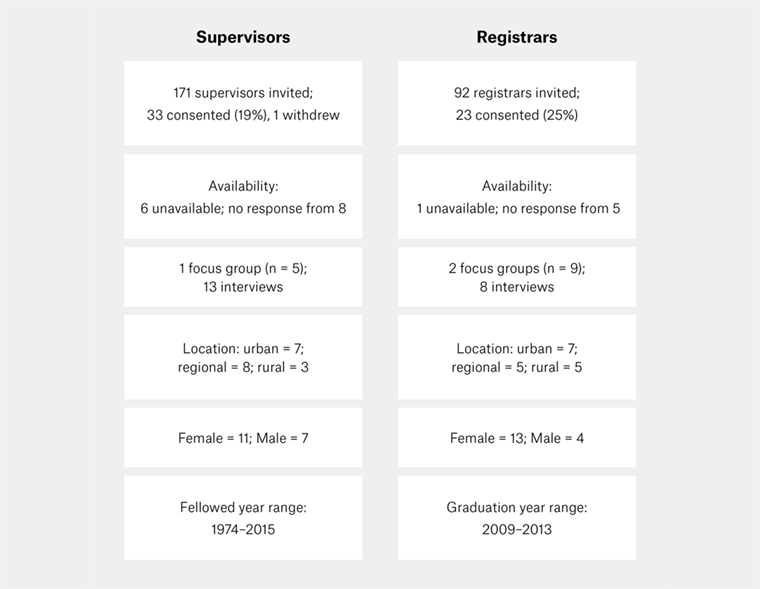

One hundred and seventy-one supervisors and 92 registrars were invited to participate in the study. From the 55 who consented to participate, three focus groups and 21 interviews were conducted, involving 18 supervisors and 17 registrars (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Recruitment, consent and participation of general practice supervisors and registrars

Figure 1. Recruitment, consent and participation of general practice supervisors and registrars

The main themes were grouped as: context influences exposure to older patients; opportunities for continuity of care need ongoing negotiation and communication; registrars are competent – trust and confidence follows.

Context influences exposure to older patients

Registrars entering general practice training have recent hospital experience and, while they are familiar with ward environments, they find older people with chronic conditions living in the community are different to patients in hospital.

You get an idea of who requires admission to a nursing home versus who is actually appropriate to be independently living. I don’t think that’s an easy thing to do coming from hospital where you see people in such awful states. (Registrar, female, region C focus group)

In the practice, particularly in their early placements, registrars often manage more acute ‘walk-ins’, mostly children and younger patients but also some older patients. When they do see older patients, it is often for pressing concerns rather than the patients’ ongoing conditions.

Older patients [are] more likely to have an established GP. Registrars … often get more acute presentations … and they often would be younger patients. (Registrar, male, region A interview)

Even if [older patients] see the registrar, they’ll usually see them about some acute problem … but not for the chronic ongoing management of that chronic problem. (Supervisor, female, region C focus group)

Most participants agreed that placement lengths can be too short for continuity of care.

Most people prefer to see their usual doctor. They have more confidence in someone who’s known and seen them over a period of time. The registrars, by definition, aren’t going to have as many, if any, chronic disease management patients, because they’re just there for six months and then gone. (Supervisor, male, region B interview)

Some smaller practices have a more explicit team approach to older patients.

Nearly all our doctors work part time, and so every now and then the continuity of care issue comes up, of course, and so we have to talk about how we work as a team. We’ve all got everyone’s notes, we speak to each other … we have a good messaging and follow-up with pathology system, and patients accept that’s just how it is. (Supervisor, female, region C focus group)

We’re a smaller practice … and I feel like it’s a very tight team … it’s like, I don’t have time to do it, so you can go ahead and do the review this time, and just tell me if you notice anything that I might have missed because I have been seeing this person for 20 years. (Registrar, male, region B focus group)

Practice nurses have a useful role in supporting registrars in chronic disease management.

[The registrar] does get support though through … a nurse practitioner [with] special interest in training in general practice and chronic disease management. (Supervisor, female, region C interview)

We have some [nurses] that are specifically advanced chronic disease management nurses ... so, the chronic disease nurses are very in tune with that area. (Registrar, female, region B focus group)

While this study focused on in-practice aged care, many participants commented on exposure to patients in residential aged care facilities (nursing homes). Participants reported positive and negative experiences of visiting residential aged care facilities.

Helping out with nursing homes cover is a way of getting more geriatric care. They mightn’t be doing plans as such, but they would be getting … a lot of exposure relatively quickly in a short period of time. (Supervisor, male, region B interview)

We were given nursing home patients in my General Practice Training 1 (GPT1) Term at the nearby nursing home with not a lot of guidance. I found that extremely stressful and have completely avoided aged care until now where there’s a completely different approach to how I get to interact with older patients. (Registrar, female, region C focus group)

However, not all practices visit residential aged care facilities.

The main idea was to be helpful and to have exposure to nursing homes, which is not that easily available to everybody, because not every GP does nursing home visits … a lot of practices are just not that interested in doing it. (Registrar, male, region B focus group)

Opportunities for continuity of care need ongoing negotiation and communication

Selecting older patients to follow during placement needs to be negotiated, and communication with older patients is important.

I have had a few patients where … perhaps they couldn’t get in to see me, they’ve gone over to see the registrar and we’ve had a chat, and they’ve said, maybe I’m happy to take them on if you want. In some cases, I’ve taken back a few patients, and in other cases I’ve just supported [the registrar] in continuing to see them. Because obviously there’s a lot to be gained in having the challenging patients. (Supervisor, female, region C interview)

I think it was a good idea for [my supervisor] to hand over some of his patients, explain to them that he was taking a step back, which he did with quite a few of them. And that gave us the opportunity to look after old patients that he’d had for a long time. (Registrar, female, region C interview)

When there is shared care, it tends to be ad hoc and informal.

There’s a bit of shared caring that seems to happen a little bit … hopefully that means that you can still be involved in the care of an older patient but there’s a long-term doctor to see them through that they can go back to who is also familiar with their care. (Registrar, female, region C focus group)

There may be advantages for older patients in being seen by registrars, who can bring a fresh perspective to seeing older patients.

There were [other patients] who were really excited to have a new set of eyes and someone more up to date. (Registrar, female, region C interview)

However, many supervisors felt that not all patients are deemed suitable for sharing with registrars.

We try and keep our elderly people with one doctor if possible, so the registrars probably don’t get as many as they might do, but I don’t think it’s fair on the patients to be expecting them to see a different doctor each time. (Supervisor, female, region C focus group)

Yet registrars often see older patients while the regular GP is away. Here, good-quality case notes on complex comorbidities help the supervisor and registrar.

I’m pretty fastidious about doing management plans and keeping track of what’s due with people … so I’ve had some pleasant surprises, really, when I’ve reviewed the notes and gone, well I’m glad that [the registrar] did that, they’ve picked up on that and they’ve changed that, and I haven’t had any problems with what any of them have done. (Supervisor, female, region C focus group)

Keeping past histories up to date would be really helpful and not with stuff that’s completely irrelevant in the active past history. (Registrar, female, region C focus group)

Notwithstanding the challenges of maintaining continuity of care for older patients, supervisors and registrars can still take the initiative in creating opportunities for aged care exposure.

Asking the supervisors to be on the lookout for specific aged care consults that they have and to either call a registrar in, or to discuss it during the lunch break on that day. (Registrar, male, region C interview)

It’s up to the registrar as well to be proactive; if you’re not seeing many older adult patients, it might be [that] the receptionists aren’t booking them in with you, and you can have a chat with them about that, you can have a chat with your supervisor about it. (Registrar, female, region B focus group)

Registrars are competent – trust and confidence follows

Supervisors acknowledged that registrars are seen to be generally competent but recognised that registrars need to develop confidence to take on care of older patients.

I think it’s a common situation where registrars are less confident with complex multimorbidity aged care patients. (Supervisor, female, region C interview)

We’ve usually found that their competence has exceeded their confidence. (Supervisor, female, region C focus group)

Confidence to take on care of older patients comes with time. Supervisors observed that registrars in later training terms are more confident, and these registrars agreed.

The majority seem to increase their confidence over time. It usually takes more than that first term … by about the second or third term, certainly I’d say my experience is their confidence is up. (Supervisor, female, region C interview)

In my experience, it’s something that you very much build up over time, so often in a month or two I find I see very few older patients, but then they might come and see you about a [urinary tract infection] or something, and then they’ll actually start coming back to see you about some of their other chronic conditions. (Registrar, female, region B focus group)

It was perceived that registrars are trusted by older patients when these patients understand the role of registrars.

I don’t think [our patients] have a problem with seeing the registrar … most of them don’t understand what [a registrar] is, but if they’re not happy with the care they’ve received they’ll express their concerns to the next doctor they see. (Supervisor, female, region C focus group)

… mostly what they say is, are you sure you’re old enough to be a doctor? And then you reassure them that you are and they move on and they’re quite happy, I find. (Registrar, female, region B focus group)

Discussion

This study accords with the findings from quantitative research on the limited exposure of general practice registrars to, and challenges for continuity of care for, older patients with chronic disease.2,3,4,6 Our qualitative study builds on those findings. We found in this group of supervisors and registrars that enabling continuity of care between registrars and older patients is highly context dependent, requires ongoing negotiation and matures with the length of the registrar placement. Still, the challenge remains as to how to increase exposure to older patients with chronic conditions by general practice registrars while maintaining continuity of care.13

A goal for a model of shared patient care in general practice would allow shared chronic disease management between supervisors and registrars while maintaining continuity of care.13 However, the findings from this study do not point to a model of shared patient care that suits all practices and supervisors. Shared care requires a high level of trust and respect between team members and is ‘highly dependent on how providers work out their shared arrangement’.14 The management of multimorbid conditions in general practice presents challenges in delivering patient-centred continuity of care.15 While ideas for shared patient care – such as maintaining good case notes, negotiating handover of patients, and registrars conducting management plans – are important, relational continuity between the GP and patient is significant to care of patients with multimorbidity.15 Many supervisors and registrars in this study agree that short (6–12 months) registrar terms limit aged care exposure and opportunities for continuity of care.

The involvement of patients in decisions about shared continuity of care is crucial.16,17 Trust between doctors, and in doctors by their patients, is central to general practice.18 Patients who have better self-rated health and trust the practice are more likely to feel comfortable with registrars’ care.19 Our participants perceived that registrars are trusted by older patients when these patients understand the role of registrars. Moreover, there is accord that registrars are generally seen to be competent but need confidence to take on care of older patients (some of which comes with time). While registrars can exercise initiative in increasing their exposure to older patients, it remains the responsibility of supervisors to determine the professional activities in aged care that can be entrusted to registrars.18 One way to increase exposure to older patient could be to discuss with registrars the importance of care of older patients with chronic disease in general practice,19 and to embed in-practice aged care activities (based on the registrar’s skills and experience) in individual learning plans at the outset of placements in general practice. Entrustable professional activities (EPA) are being used in general practice20,21 and offer ‘a means to translate competencies into clinical practice’.18 For example, care of an older patient with chronic disease is an EPA that requires knowledge, skills and attitudes.20 Developing tailored models of shared patient care that suit different general practices and supervisors will require ongoing negotiation and communication, particularly given the tension between providing experiential teaching and maintaining continuity of care.22 We recognise a need for further conversations between regional training organisations, supervisors and registrars about ways to formalise exposure by registrars to older patients with chronic conditions.

Study limitations

The strong response to study invitations allowed for purposive sampling, resulting in a maximum variation sample with participation by supervisors from urban and regional practices with a range of experience as GPs. Registrars were at all levels of general practice training and were also working in urban and rural practices. More female registrars than male registrars participated in the study. The perspectives of patients were not part of the study. However, our themes are accordant with findings from other Australian studies on older patients and registrars.16,19,23

The study is specific to the Tasmanian context. However, the findings accord with themes of trust and continuity of care from other Australian studies.2,4,19,24 Thus, the study offers insights into the challenges for a shared-care approach to aged care management in general practice.

Implications for general practice

This study highlights the need to create conversations about formalising exposure of general practice registrars to older patients with chronic conditions:

- Regional training organisations, registrars and supervisors should formally discuss aged care as an area of focus early in training.

- Conversations could include developing agreed strategies based on the competence of registrars and the trust in registrars by older patients and supervisors.

- These conversations can provide a basis for developing practice-based models to increase registrars’ exposure to, engagement with, and continuity of care for older patients with chronic disease.

- Models that are acceptable to registrars, supervisors, patients and practices will need to be tailored to account for the determinants of general practice and the context in which they operate.2