Feature

‘Renewal from the ashes’: Ten years on from Black Saturday

Survivors and healthcare professionals reflect on the impacts of the disaster, including the long and complicated recovery.

After the fires, the recovery remains ongoing. (Image: Joe Castro)

After the fires, the recovery remains ongoing. (Image: Joe Castro)

When the Black Saturday firestorm came to Marysville in Victoria’s Yarra Valley on 7 February 2009, GP Dr Lachlan Fraser tried to save his home and clinic – without success.

He saved his two dogs and fled to the nearby football oval, where he and around 30 others spent the night as fires raged on all sides.

‘Even with preparation, nobody is ready for a disaster. You operate on instinct and rational, drawing on personal reserves and resources around you,’ he wrote afterwards.

Nursing a burned cheek and cut tendons in his hand from trying to save his house, Dr Fraser and ambulance crews tended to the injured – men with bad burns, an unwell pregnant woman, and many with smoke-affected eyes. He treated a woman who had been injured when a large tree fell on her car.

He later wrote: ‘As the town’s doctor, I began to assess her injuries. She was concussed and kept asking, “Where are my cats? Where is my mother?”.’

When morning came, the survivors were evacuated as emergency services moved in. The town had lost 34 people. Almost every building was destroyed. Dr Fraser was taken to hospital, and later took shelter with his mother in Melbourne, 70 km away.

Six weeks later, Marysville locals were allowed back to see what was left of their town.

‘We got together, the survivors. As someone known in the community, I felt it was important to be present, and to talk to people,’ Dr Fraser told newsGP.

‘Everyone offered each other support. There was an incredible amount of hugs and tears.

‘The whole town was distressed. For people directly involved in the bushfire, it’ll probably be the biggest single event in their lives, as far as impact and memories of it go.’

After the fire came the slow, hard recovery from the trauma, with huge demand for mental health support. Dr Fraser counselled many of his patients.

‘There was plenty of anxiety and depression after the fires, some alcohol and drug abuse and some relationship problems,’ he said.

‘People had what we called “bushfire brain” in the early days of muddling through.’

Many threw themselves into the recovery effort as a way to deal with what had happened.

‘There was a real bonding together as a community. So many people put in the work to put back a complete town as you see it today,’ Dr Fraser said.

‘In terms of learning resilience and showing endurance, there was certainly positive growth.’

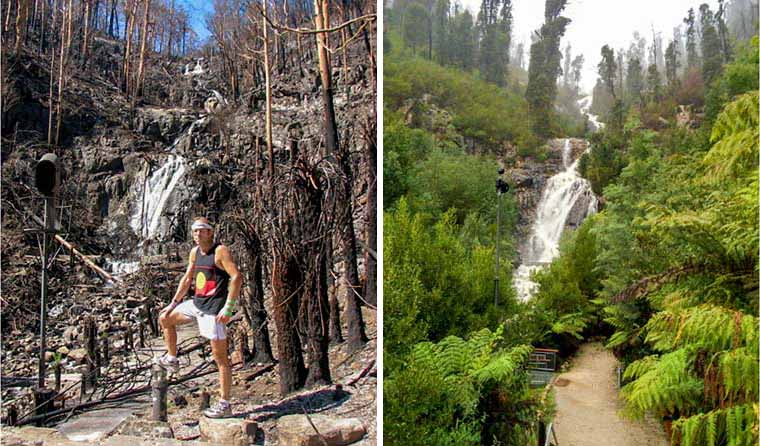

From left: Dr Lachlan Fraser at Steavenson Falls, 4 km from Marysville, in the aftermath of the Black Saturday fires; and the regrown area as it looks today.

Like others, Dr Fraser threw himself into community life, going to meetings, talking to people on the streets.

‘As GPs, we have a role in terms of people skills, so in such a disaster we can play a major role in recovery. You step up to the plate,’ he said. ‘I’m not sure if it’s obligation, but you feel that duty calls, I suppose.’

Before the fires, Dr Fraser had been living a quiet life on his own. But afterwards, the community’s need drove him into a frenzy of activity. It was an intensely busy time. Dr Fraser’s car engine blew up because he’d simply been too busy to put oil into it.

‘Everyone’s life got put on hold for a couple of years,’ he said.

Only when the pace slowed did he take stock of his own trauma.

‘You run on adrenaline, and then you can have a flat period. I missed some work,’ he said.

But Dr Fraser, a keen runner, kept forging on. He set about organising the first Marysville Marathon as a way to bring people to the area and allow them to show their support. He’d had the idea in the first week after the fire, tapping out his ideas with one hand in a cast. In November 2009, the first runners set off.

While organising the first marathon, Dr Fraser met Cassandra Church, a nurse from nearby Alexandra, and love unexpectedly bloomed. The married couple’s daughter is now seven years old.

‘I’m really blessed. It shows you what can happen around the corner,’ Dr Fraser told the Herald Sun in 2012.

‘[She’s] a reflection of the love between us. It’s the next generation coming along; it’s renewal from the ashes.’

‘As far as impact and memories go, the fire is bigger than births deaths and marriages – and in my catastrophe, I had more than one of those,’ Dr Fraser told newsGP.

Ten years later, many have rebuilt their lives.

‘We’ll never forget within ourselves. We’ve always got it in our psyche,’ Dr Fraser explained.

‘We get on edge with fires. But we have experience, so in one sense we are better prepared for when other fires threaten. We don’t want people to forget if there’s a situation in the future.’

Psychological first aid

On 7 February 2009, Michelle Roberts was working as a school psychologist in Kilmore, 60 km north of Melbourne. A power line fell in high winds and sparked one of the major fires only a kilometre away.

‘We had to go straight into a response strategy to ensure students were safe. It was an intense period, waiting to hear, and then supporting staff and students who had a horrific experience,’ she told newsGP.

Ms Roberts, who works with the Victorian Department of Education in disaster recovery, has worked in the aftermath of the 1983 Ash Wednesday fires, as well as after the 2002 Bali bombings, 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, and a number of other natural disasters.

In the immediate aftermath of Black Saturday, Ms Roberts and other psychologists administered psychological first aid, such as teaching young children how to regulate their stress responses.

‘When I’ve spoken to young children, their fear has been that their heart will literally break, because it’s beating so fast that it’s hurting very much,’ she said. ‘Arousal regulation is a red flag for risk, so we teach them to bring down that physiological response.’

Ms Roberts has worked extensively with affected children and young adults over the decade since Black Saturday.

‘In 1983 [following Ash Wednesday,] there was very little recognition of the ongoing effects of disasters for children and young adults. We’ve come ahead enormously since that time, but we still need evidence-based research,’ she said.

Psychologist Michelle Roberts has worked extensively with affected children and young adults over the decade since Black Saturday. ‘The effects are still most definitely being felt and some are only now emerging,’ she said.

Psychologist Michelle Roberts has worked extensively with affected children and young adults over the decade since Black Saturday. ‘The effects are still most definitely being felt and some are only now emerging,’ she said.

Ms Roberts co-authored recent research showing that the 2009 fires still affected young people’s academic grades years later, with expected gains in literacy and numeracy lower in schools with higher levels of bushfire impact.

‘The effects are still most definitely being felt and some are only now emerging,’ she said.

‘We know that children who weren’t even born have changed circumstances because of their family’s experiences. We know that some schools are only now having their first cohort of toilet-trained preps [after the fires].

‘So, for some children, that developmental trajectory changed significantly.’

For young adults, the effects can be seen in a loss of hope, or even a loss of ability to separate from their parents and move on to university.

‘Some are much more happy and content to be where their family is, which can impact on their ability to grow,’ Ms Roberts said.

Ms Roberts said other long-term impacts include the use of alcohol as a coping mechanism and an associated uptick in family violence.

But she said there has been major progress in disaster-prone areas, giving children the knowledge on how to survive and thrive.

‘We need to be giving young people the skills to protect themselves, and not just physical, but mental protection.’

Many parents also report struggling to look after their children after such a disaster.

‘Parents are dealing with their own trauma responses. Avoidance is characteristic, so it’s almost impossible to bear the reality that your child is suffering like you are,’ Ms Roberts said.

‘Even following through on tasks can be a real challenge when you’re in survival mode. Just making a sandwich is very difficult in the early stages.’

Ms Roberts said it is very common for parents to feel like putting boundaries in place is pointless.

‘Parents are busy rebuilding their physical location, their own sense of safety and wellbeing. They can lose the ability to put boundaries in place – “Why does it really matter if they stay up till 10.00 pm if we just nearly died?”’ she said.

‘Parents can also feel a sense of shame or loss of agency, shame that they chose to live in an area where they might be at risk. They might feel ashamed at their own panic or hysteria response.

‘There are some really good disaster parenting programs around, but it can be hard to know when to offer them, to know when people are ready to take them in.’

Ms Roberts said GPs are vital to ongoing community recovery efforts.

‘GPs interact one-on-one, so there’s an opportunity to engage with where people are at. It’s a distinct advantage compared to dealing with big communities at one go,’ she said.

‘I’m very mindful that lots of GPs were impacted themselves. Those of us, the helpers, were often impacted either directly or vicariously.

‘Early research found children and young people were most likely to turn to their GP or teacher when they were struggling emotionally after a disaster, so the more prepared a GP is, the better.

‘Collaboration between GPs and schools needs to be strengthened in these circumstances, as in all likelihood [doctors and teachers] will be working with the same children. Recovery needs to target mind, body and soul and work across all domains.’

After the fact

For GP and disaster medicine expert Dr Penny Burns, the anniversary of the fires is a reminder that a disaster has a very long tail.

‘For adults, we know that not only are there mental health effects playing out five to 10 years later, but physical effects as well,’ she told newsGP. ‘There are documented physiological changes to heart rate, blood pressure, deterioration of chronic conditions and higher risk of strokes and myocardial infarctions.’

‘Since the fires in 2009, we’ve learned a huge amount, especially around mental health. The majority recover well, but some don’t. We now have a much better system of early psychological support for people after events like this and a systematic method of delivery,’ she said.

‘A key group providing that are GPs. We now know from talking to GPs after the bushfires that patients turned up to trusted health professionals – and that’s their GP. In the waiting rooms, people gathered, expressed distress and sought support.’

Dr Burns said that GPs are ideally placed on the ground to deal with subsequent events.

‘After the bushfires, the swine flu pandemic came through two months later. People still have health stresses, financial stresses. The disaster doesn’t happen in isolation,’ she said.

‘Local GPs get a good sense of what’s happening in that community. They’re very aware of what people are going through, and can identify patients in more need of care.’

Black Saturday disaster primary care recovery

newsGP weekly poll

As a GP, do you use any resources or visit a healthcare professional to support your own mental health and wellbeing?