News

Air pollution may have increased COVID-19 deaths by 15%

Researchers have been able to estimate the proportion of deaths for the first time.

Study estimates show air pollution contributed to 3% of Australia’s COVID-19 deaths.

Study estimates show air pollution contributed to 3% of Australia’s COVID-19 deaths.

Previous studies have linked air pollution to COVID-19 mortality, but researchers have been able to estimate the proportion of deaths for the first time.

An international study estimates that about 15% of COVID-19 deaths worldwide could be attributed in part to long-term exposure to air pollution, specifically ambient fine particulate air pollution (PM2.5).

Regionally, the proportion is 27% in East Asia, 19% in Europe, 17% in North America, and 3% in Oceania.

When the percentage is broken down into actual deaths from comorbidities such as cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, co-author and atmospheric chemist Professor Jos Lelieveld says the numbers are staggering.

‘As an example, in the UK there have been over 44,000 coronavirus deaths and we estimate that the fraction attributable to air pollution is 14%, meaning that more than 6100 deaths could be attributed to air pollution,’ he said.

‘In the USA, more than 220,000 COVID deaths with a fraction of 18% yields about 40,000 deaths attributable to air pollution.’

Associate Professor Vicki Kotsirilos, a GP and member of the RACGP Specific Interests Climate and Environmental Medicine network, says the findings serve as a ‘significant wake-up call’.

‘I personally was excited to read this study because it is an improved higher quality study compared with initial observation studies in Europe [that] found that there was an association between air pollution, particularly the finer particulate matters 2.5 (PM2.5) and less, with increased risk of COVID deaths,’ she told newsGP.

‘The 15% finding of mortality is actually a really significant increased risk of death associated with COVID.

‘What it means is that we need to now see air pollution as a bigger health problem and particularly in the future should we have ongoing infections, because like we’re now having the COVID pandemic, there will be other pandemics.’

In Australia, study estimates show air pollution contributed to 3% of COVID-19 deaths and just 1% in New Zealand, compared to 27% in China, 26% in Germany, 18% in France, 16% in Sweden, 15% in Italy and 12% in Brazil.

The authors cite Australia as a positive example, claiming increased mortality linked to air pollution could have been avoided had countries adopted Australia’s air quality regulations of an annual PM2.5 limit of 8 mg/m3.

Associate Professor Kotsirilos believes Australia’s effective health response may have also played a role.

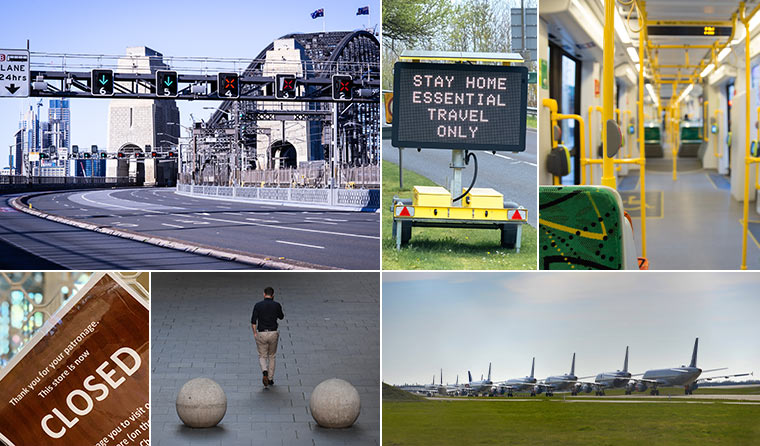

‘The health authorities were excellent in the way we addressed COVID fairly quickly and the lockdowns actually led to a reduction in air pollution, as there were a lot less vehicles on the road, and therefore the air was cleaner,’ she said.

‘That in itself may have helped as well to reduce morbidity and mortality – so that’s good news.’

Associate Professor Vicki Kotsirilos says the research is a ‘significant wake-up call’.

The new findings are based on epidemiological data from previous US and Chinese studies of air pollution and COVID-19 and the SARS outbreak in 2003, supported by additional data from Italy.

Researchers combined that with satellite data showing global exposure to PM2.5, information on atmospheric conditions and ground-based pollution-monitoring networks to create a model to calculate the fraction of coronavirus deaths that could be attributable to long-term exposure to PM2.5.

Given that data have been collected in middle- to high-income countries, the authors note that calculations carried out for low-income countries may be less robust.

According to co-author and vascular biologist Professor Thomas Münzel, when people inhale polluted air the PM2.5 migrate from the lungs to the blood and blood vessels causing inflammation and severe oxidative stress, resulting in an imbalance between free radicals and oxidants in the body that normally repair damage to cells.

‘This causes damage to the inner lining of arteries, the endothelium, and leads to the narrowing and stiffening of the arteries,’ he said.

‘The COVID-19 virus also enters the body via the lungs, causing similar damage to blood vessels, and it is now considered to be an endothelial disease.

‘If both long-term exposure to air pollution and infection with the COVID-19 virus come together then we have an additive adverse effect on health, particularly with respect to the heart and blood vessels, which leads to greater vulnerability and less resilience to COVID-19.

‘If you already have heart disease, then air pollution and coronavirus infection will cause trouble that can lead to heart attacks, heart failure and stroke.’

Globally, 50–60% of the attributable anthropogenic fraction was found to be related to fossil fuel use, and 70–80% in Europe, West Asia and North America, indicating the potential for substantial health benefits from reducing air pollution exposure.

Associate Professor Kotsirilos said the findings put air pollution up there with smoking as a risk factor for COVID.

‘It tells us that air pollution is a risk of morbidity and mortality like smoking and that we should be addressing air pollution, particularly in areas with a high pollutant levels such as within cities where there’s lots of people living, working, or even schools that are situated near freeways and heavy-traffic roads, as well as people living in regional areas near coal-fired power stations,’ she said.

‘Just as we have successfully addressed smoking and we’re seeing reduced numbers amongst our patients, we also need to address air pollution.’

Associate Professor Kotsirilos’ message is in line with that of the authors.

In light of the research, they conclude there is a need to accelerate efforts to reduce anthropogenic emissions that cause both air pollution and climate change.

‘Our results suggest the potential for substantial benefits from reducing air pollution exposure, even at relatively low PM2.5 levels,’ the authors wrote.

‘The pandemic ends with the vaccination of the population or with herd immunity through extensive infection of the population. However, there are no vaccines against poor air quality and climate change. The remedy is to mitigate emissions.

‘The transition to a green economy with clean, renewable energy sources will further both environmental and public health locally through improved air quality and globally by limiting climate change.’

Log in below to join the conversation.

air pollution COVID-19 mortality

newsGP weekly poll

Are you interested in prescribing ADHD medication?