News

Almost 30,000 cancers over-diagnosed a year: Research

But an expert says it is a ‘tricky balance’ between over-diagnosis and adequate detection of cancer.

The new The study shows that, compared to 30 years ago, Australians are now much more likely to experience a cancer diagnosis in their lifetime.

The new The study shows that, compared to 30 years ago, Australians are now much more likely to experience a cancer diagnosis in their lifetime.

Approximately 18,000 cancers in men (24%) and 11,000 cancers in women (18%) were over-diagnosed in Australia in 2012.

Such were the findings of new research published in the Medical Journal of Australia.

The study shows that, compared to 30 years ago, Australians are now much more likely to experience a cancer diagnosis in their lifetime.

Researchers defined over-diagnosis as the diagnosis of cancer in people who would never have experienced symptoms or harm had it remain undetected and untreated.

Using routinely collected Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) national data, researchers estimated recent (2012) and historical (1982) lifetime risks – adjusted for competing risk of death and changes in risk factors – of diagnoses for five cancers:

- Breast

- Prostate

- Renal

- Thyroid

- Melanoma

GP and lead researcher Professor Paul Glasziou told

newsGP the findings were in line with other research performed internationally. However, he said the overall number of people who had been over-diagnosed in Australia was ‘surprisingly high’.

He believes there are a number of reasons this is occurring. For instance, breast cancer over-diagnosis occurs largely due to the effect of routine screening practices.

Yet Professor Glasziou believes increased ordering of thyroid function tests (TFTs) and thyroid ultrasound contribute to the high diagnosis of such cancers, while over-ordering of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests plays a role in the over-diagnosis of prostate cancer.

‘There are GPs who I’ve heard of who, for example, order a PSA on somebody without even their consent,’ he said. ‘That’s inappropriate.’

Professor Glasziou is concerned about the effects of over-diagnosis.

‘The main potential harm for patients is that they get over-treated for something that never would have caused a problem in their lifetime,’ he said.

‘So 40% of men who are now being detected as having prostate cancer are men who never would have presented clinically in their lifetime.’

‘But what happens to them is that they then get told they have prostate cancer, they then get a prostatectomy, they may have radiotherapy or chemotherapy later on.

‘The prostatectomy, of course, the side effects are not just the direct risks of surgery, but the majority of men will end up impotent and have incontinence.

‘Some of it reverses over time, but some of it won’t.’

Similarly, Professor Glasziou said the risks of an unnecessary thyroidectomy, including lifelong thyroxine replacement and unnecessary surgery, are also significant.

‘It’s not just the economic cost; it’s about the harm to patients from this over-detection,’ he said.

Jon Emery is a Professor of Primary Care Cancer Research at the University of Melbourne. While he said this new paper is important, as it quantifies the ‘potential size’ of over-diagnosis, he told

newsGP he harbours some concerns.

‘Some of the issue is about the balance of the benefits from early detection weighed against the size of over-diagnosis,’ he said.

Professor Emery said there have been a number of evidence-based reviews into the topic of breast cancer screening and its potential for over-diagnosis, for example.

‘And the benefit in terms of mortality reduction that you get from randomised controlled trials of mammography screening is such that the benefits of early detection and reduction mortality at a population level are felt still to be large enough to warrant offering biannual screening to the population,’ he said.

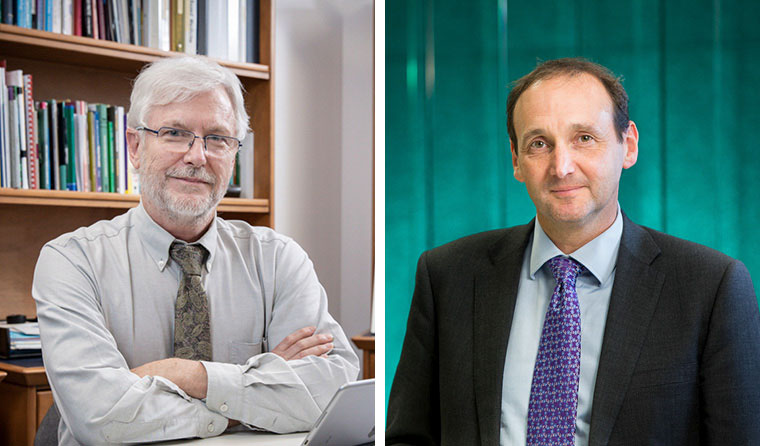

L–R: Professor Paul Glasziou said the overall number of people over-diagnosed was ‘surprisingly high’.; Profesor Jon Emery believes some of the issue is about balancing ‘the benefits from early detection weighed against the size of over-diagnosis’.

L–R: Professor Paul Glasziou said the overall number of people over-diagnosed was ‘surprisingly high’.; Profesor Jon Emery believes some of the issue is about balancing ‘the benefits from early detection weighed against the size of over-diagnosis’.

Professor Emery said recognition is needed that some of these women will experience over-diagnosis and potential over-treatment of a cancer that would not have caused them any harm.

‘But, overall, the benefits of breast cancer screening are still thought to outweigh potential harm of over-diagnosis and overtreatment,’ he said.

Professor Emery said the issue changes when it comes to prostate cancer, because the benefits in terms of early detection and reduced mortality ‘are much less clear’.

‘There has been a response to this issue [of over-diagnosis] in terms of trying to identify those slow-growing cancers, and that’s currently done on Gleeson score and then offering active surveillance,’ he said.

‘One response to the problem of over-diagnosis is trying to reduce over-treatment by monitoring those prostate cancers to get a better sense of whether these are actually true over-diagnosis cancers that are going to continue not to grow very rapidly, or if there’s a find that this is a tumour that’s beginning to grow, then treating it at that point.’

He said the urological community has responded to this dilemma by engaging active surveillance to reduce over-treatment, which can help reduce the impact of over-diagnosis.

When it comes to balancing the risks of over-diagnosis versus potential benefit, Professor Glasziou agrees each cancer is different, and some over-diagnosis is unavoidable.

‘We need to be wary of using “five-year survival” to look at the value of early detection,’ he said.

‘Cancer survival rates are a very poor indicator, as they are biased by early detection.

‘Over-diagnosis is great for “apparent” survival, as they are non-life-threatening, so increase the cancers but appear to reduce the percentage dying.

‘That is why we look at age-specific mortality only, to avoid the bias from survival from diagnosis.’

Professor Glasziou also believes more should be done to address the problem of over-diagnosis. When it comes to prostate cancer, for example, he said PSA tests should only be ordered as per the RACGP’s guidelines.

‘The biggest thing I would say is for GPs to be aware of, and use, the

Red Book [

Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice],’ he said.

‘The Red Book is very clear you should only do PSA screening if there’s been an informed consent process.’

Professor Glasziou also believes greater awareness of the problem is needed within general practice.

‘I would say across the board most GPs are not aware of it, or certainly not aware of the extent of it,’ he said.

‘One of the reasons we want to reduce this is the problem has gone up over the last one or two decades and as new tests come along, we increase the amount of testing we do.

‘There’s a potential that this problem will just keep increasing.’

Professor Emery is less concerned about the potential issue of over-diagnosis, and instead believes more focus is needed on reducing over-treatment.

‘The problem always is that at an individual level it’s not possible to say for sure a cancer that we’ve detected through screening is definitely one of these slow-growing cancers; that is an over-diagnosed cancer,’ he said.

‘That’s part of the problem that at the moment we can’t say precisely enough at an individual level that you’ve definitely got an over-diagnosed cancer.’

The issue of over-diagnosis versus adequate detection of cancer is complicated, Professor Emery said.

‘It is a very tricky balance,’ he said.

‘I think the danger of the over-diagnosis argument gets overstated without really thinking about the other beneficial outcomes.

‘Australia has some of the best cancer outcomes in the world and that’s partly through screening and partly through having good access to investigations.

‘Some of the over-diagnosis is an inevitable consequence of that.’

Log in below to join the conversation.

cancer over-diagnosis over-treatment

newsGP weekly poll

Which of the following areas are you more likely to discuss during a routine consultation?