Feature

Are COVID death rates really falling globally?

Around the world, COVID is becoming a disease of younger people, and death rates may be tracking lower. But experts warn against complacency and reliance on at-times rubbery data.

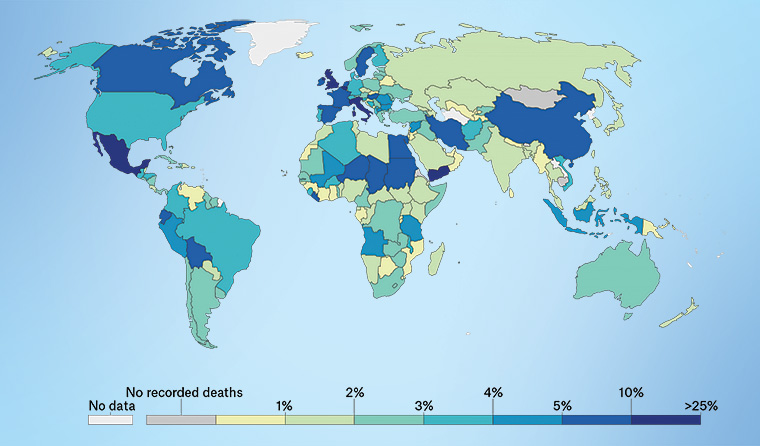

Map showing recent global case fatality rates. (Source: Our World in Data)

Map showing recent global case fatality rates. (Source: Our World in Data)

On the surface, it seems like positive news – the coronavirus appears to be killing fewer people per number of cases in some countries.

In hard hit nations like the US, the case fatality rate (CFR) now sits around 3% – and the numbers of deaths has dropped from around 3000 per day in April to around 1000 on a seven-day rolling average.

It is a similar story in the badly affected UK, where the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine now estimates the CFR has fallen from over 6% down to around 1.5%.

Some developing countries are also seeing similar trends, with coronavirus-stricken Brazil now registering a CFR of around 3.1%, while deaths per day seem to have dropped.

Overall, the pandemic is still growing, with the number of deaths now over 905,000 worldwide out of 27.89 million cases, giving a global CFR of around 3.2%.

New research by Chinese and American researchers suggests a broad drop in death rates has occurred with around 80% of the worst hit nations experiencing lower CFR estimates between the first and second waves of the virus.

Leaders and media outlets in some countries have seized on these findings to suggest the pandemic is becoming less dangerous.

But is this accurate? And if so, why would the case fatality rate – a notoriously rubbery figure measuring deaths per number of confirmed cases – be falling in some nations and not others?

Most experts approached by newsGP say it is too early to tell, and that these figures should not be relied on due to the difficulty in capturing all infections and all COVID-related deaths in the data.

They say the virus kills more people when health systems are overwhelmed, or in nations where there are many older people or people with comorbidities, such as Italy, meaning CFRs can bounce around.

But they also say there are observable trends that could drag the fatality rate lower, such as the fact the virus is now being spread by the young – who are more likely to survive it.

Additionally, proven treatments such as dexamethasone and simple but effective techniques such as proning have helped more people survive the acute respiratory distress seen in the severe form of the disease.

Lockdowns may have also played a part in pushing death rates lower, with stricter lockdowns and widespread testing linked to declining death rates in a Journal of Translational Medicine study comparing seven nations in Europe and the USA.

UK-based Professor of Medicine Paul Hunter told newsGP that better treatments and techniques, as well as more younger people contracting the virus and surviving, were likely causes for any drops seen.

The University of East Anglia researcher has previously pointed out that the disease now seems to be spreading more among younger people than was the case in March, April and May.

‘As we all know the case fatality rate is substantially lower in younger people that in older people. This is the case within Europe and also the case globally with the disease now spreading in countries with much younger populations,’ he said.

‘As doctors’ experience at managing the disease increase they are becoming better at keeping patients alive … [and] as testing becomes more readily available we are now diagnosing a higher proportion of cases than a few months ago.

‘In March and April we were generally only diagnosing the more seriously ill and, therefore, the people most likely to die. Just being able to add the numbers of mild illnesses now being diagnosed to the total figure will drop the case fatality rate.’

However, La Trobe University epidemiologist Associate Professor Hassan Vally told newsGP the large number of variables means it is not possible to conclusively say the case fatality rate is reducing.

‘It is very much like comparing apples with oranges when comparing COVID statistics between countries as there are very different testing regimes, that also change over time, as well as a range of other differences,’ he said.

‘One of the factors that would artificially elevate CFRs is if you only test and confirm illness in individuals with severe disease, as was being done in many places throughout the world that were overwhelmed in the early stages of the pandemic.

Associate Professor Hassan Vally believes it is not possible to conclusively say the case fatality rate is reducing.

‘Also, one of the big influences on the CFR is the ability of the health system to cope with the pandemic, and if the health system is not able to cope then you would expect to see a greater case fatality rate.’

But Associate Professor Vally said there is a distinct trend towards younger people getting the virus in Australia and other countries.

‘We are certainly seeing a change in the demographics of those that are contracting disease, with a greater proportion of younger individuals, who generally have milder illness, getting COVID-19,’ he said.

‘It is important to note that there is no strong evidence at this point in time that I am aware of that the virus has mutated to a significantly less virulent form and that this is driving the differences in CFRs that are being observed.

‘It’s [also] important to be careful about generalisations about this SARS-CoV-2 virus, as it is very different virologically to influenza and even SARS or MERS.’

University of Melbourne epidemiologist Laureate Professor Alan Lopez told newsGP he does not promote the use of the CFR as a guide to tracking the course of the epidemic.

‘Case fatality rates have errors in the numerator and the denominator. The number of deaths and the number of cases are both uncertain,’ he said. ‘It’s a really [inadequate] measure of mortality.’

He prefers the use of all-cause mortality, which captures changes in all causes of death over time.

But Laureate Professor Lopez said that it is reasonable to expect fatality rates to fall as we learn more about the disease and use proven treatments to save more lives.

‘Some of the treatments now available have cut mortality significantly,’ he said.

University of Wollongong epidemiologist Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz told newsGP he and his collaborators have to date found no decrease in COVID death rates over time in their latest preprint study on infection fatality rates and age-stratified risk.

Infection fatality rates offer a more precise metric than the CFR, by measuring death rates across all infections rather than just confirmed cases.

However, capturing all infections is a much harder task.

‘This is a complex question. Our study on age-stratified risk didn’t find a temporal decrease, but I’m not sure directly comparing across time is that easy,’ Mr Meyerowitz-Katz said.

‘While we didn’t find any evidence of it, we would expect death rates to be decreasing given there are now better treatments.

‘There are a number of studies now, especially in Europe, which find that people who are hospitalised now are less likely to die than at the peak of the epidemic in Europe in March and April.

‘But the patient population has now changed quite significantly, so it’s hard to say if it’s because of improved treatments, if COVID-19 has changed, if hospitals are less overwhelmed, or if it’s because younger people are coming in.’

In the preprint study, Mr Meyerowitz-Katz and his co-authors estimate the age specific infection fatality rates at ‘close to zero’ for children and younger adults, reaching 0.4% at age 55, 1.3% at 65, 4.5% at 75 and 15% at age 85.

‘We find that differences in the age structure of the population and the age-specific prevalence of COVID-19 explain 90% of the geographical variation in population [infection fatality rate],’ the authors write.

‘These results indicate that COVID-19 is hazardous not only for the elderly but also for middle-aged adults, for whom the infection fatality rate is two orders of magnitude greater than the annualised risk of a fatal automobile accident.’

Royal Melbourne Hospital infectious diseases clinician Associate Professor Steven Tong is the principal investigator for the Australasian COVID-19 Trial (ASCOT) and a co-lead of clinical research at the Doherty Institute.

He told newsGP there is still not enough data to determine whether mortality rates are indeed reducing – or if instead more young people are contracting the virus and not getting the severe form of the disease.

But he believes newer treatments may be playing a role.

‘Certainly the data we have suggests that the agents that work are now being used a lot more. We wouldn’t have been using dexamethasone much at the start, whereas now it’s standard care,’ he said.

‘If you’ve got lots more 20 and 30-year-old people being tested – they’re less likely to die.’

Associate Professor Tong said it is hard to know what specific treatment or technique may have made the difference to save a life.

‘Everyone is gaining experience in how to manage these cases, but it’s hard to know which exact intervention makes a difference,’ he said. ‘Lots of people are getting proned, getting dexamethasone, remdesivir and anti-coagulants.

‘We’re also intubating later and holding off where we can. There’s an appreciation that when people are on ventilators, it’s hard to get them off. If we can get them by without needing to intubate, that’s better.’

He said that better clinical knowledge has also led to a reduction in agents where there was little evidence of efficacy, such as hydroxychloroquine.

‘In the US and Europe, where hydroxychloroquine had been used in large numbers – that has now really fallen away,’ he said.

‘There’s hopefully a move to using things where there’s an evidence base.’

Log in below to join the conversation.

case fatality rate coronavirus COVID-19 mortality rate

newsGP weekly poll

As a GP, do you use any resources or visit a healthcare professional to support your own mental health and wellbeing?