Feature

Do children’s healthy blood vessels protect them from severe COVID-19?

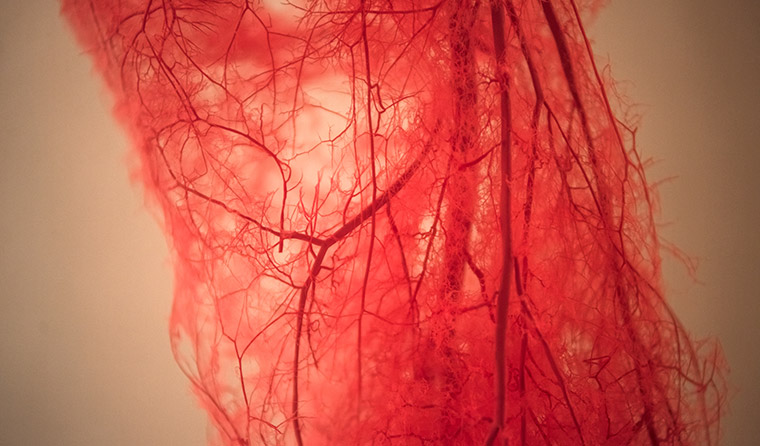

The virus is now known to target endothelial cells present in every blood vessel – and that may open up new treatment options.

The virus is now believed to target the endothelial cells that smoothly coat our blood vessels, thereby potentially gaining access to the organs to which the vessels supply blood.

The virus is now believed to target the endothelial cells that smoothly coat our blood vessels, thereby potentially gaining access to the organs to which the vessels supply blood.

For more than 20 years, paediatric haematologist Professor Paul Monagle and his team at Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital have been trying to unpack the differences between the blood vessels of children and adults.

But his research has taken on a new urgency in the era of COVID-19, as mounting evidence suggests the disease may be most dangerous due to its impact on the vascular system.

The virus is now believed to target the endothelial cells that smoothly coat our blood vessels, thereby potentially gaining access to the organs to which the vessels supply blood.

Around 40% of people who die from the virus-induced disease have cardiovascular complications, according to a Circulation Research evidence review from May.

‘This was thought to be a respiratory virus. But when you look at who gets most severely affected and those who do the worst, those are the people with cardiovascular disease, diabetes and hypertension,’ Professor Monagle told newsGP.

‘Early autopsy reports showed patients were clearly getting lots of thromboses in the lungs, so all the early evidence pointed to the fact that coagulation was a key factor in what happened.’

That, to Professor Monagle, suggested the hypothesis that the young, healthy blood vessels of children may be a major reason why they get COVID-19 much less often – and much less severely – than adults.

He recently told Newsweek that 71% of patients who die from the disease meet the clinical criteria for disseminated intravascular coagulation, whereas only 0.6% of people who recover seem to have had this condition, where small blood clots form through the bloodstream and block small blood vessels.

Professor Monagle said a potential explanation for the mortality age gradient could be the differences in the blood and clot structure, with the protection conferred by children’s developing endothelial blood interface keeping them from the worst of COVID-19.

That hypothesis is backed by interventional cardiologist Associate Professor Dion Stub, who told newsGP it is increasingly clear that COVID-19 has major impacts on the endothelium.

‘We think the impact on the endothelium is a significant part of pathogenesis,’ he said. ‘The virus enters the body through ACE-2 receptors, and these receptors are expressed in organs such as the heart, kidney and lungs, as well as significant receptors in the endothelium.

‘The reason we think that COVID has hurt the elderly – and especially patients with comorbidities such as hypertension or a history of cardiac disease – is that those patients have significantly impaired endothelial function.

‘The flipside of that is that children typically have very good endothelial function. That may be one of the mechanisms that protects children from getting it, and when they do get it, to have significantly less clinical impact.’

As the pandemic worsened in April, doctors around the world started seeing issues with blood clotting, heart inflammation, stroke and encephalitis.

That led Dr Mandeep Mehra, medical director of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart and Vascular Center in Boston, to claim the virus is likely vasculotropic, meaning it affects the blood vessels.

‘The concept that’s emerging is that this is not a respiratory illness alone; this is a respiratory illness to start with, but it is actually a vascular illness that kills people through its involvement of the vasculature,’ Dr Mehra told Elemental.

In a small study in The Lancet, Dr Mehra and colleagues found that the virus could infect – and damage – the endothelial cells carpeting the inside of blood vessels. Once damaged, the endothelium could malfunction, leading to the massive clotting seen in severe cases of COVID-19.

‘We found evidence of direct viral infection of the endothelial cell and diffuse endothelial inflammation,’ the study states.

‘Although the virus uses ACE-2 receptors expressed by pneumocytes in the epithelial alveolar lining to infect the host, thereby causing lung injury, the ACE-2 receptor is also widely expressed on endothelial cells, which traverse multiple organs.’

Endothelial dysfunction expert Dr Maithili Sashindranath told newsGP that more and more COVID-19 literature is now focusing on the virus’ impact on the vascular system.

‘COVID-19 was initially characterised as a respiratory disease, but then reports started emerging of clots across many organs. It’s a unique feature of the disease,’ she said.

‘People in intensive care often had clots in their kidneys or lungs, with the lungs of these patients often having features of endothelial injury.

‘The virus binds to ACE-2 receptors, and endothelial cells express this receptor. The literature is still evolving, but much of it is pointing to the fact that endothelial cells are a major target for COVID-19.’

Dr Sashindranath, a senior research fellow at the Monash University-based Australian Centre for Blood Diseases, said that endothelial cells regulate how blood moves through our vessels, the formation of blood clots, and also act as the gatekeeper of immune responses.

‘Endothelial cells are in every organ, as every organ has blood vessels. That means damage to them can affect any organ,’ she said.

It is possible that the healthy blood vessels of children are a major reason why they get COVID-19 much less often – and much less severely – than adults.

The emergence of a rare but potentially inflammation-based response similar to Kawasaki Disease in children and adolescents suggests to Dr Sashindranath that the virus can still infect endothelial cells in children.

‘I don’t think there’s evidence to show there is less endothelial infection in children, given that they have this new hyperactive immune response, which the endothelium could control,’ she said.

Dr Gary Gibbons, Director of the Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the US National Institutes of Health, recently said the fact that the virus affects small vessels as well as large – with clots even in capillaries – suggests an interaction between platelets and the endothelial surface.

‘Normally, there’s a tightly regulated balance in the bloodstream between pro-coagulant and anti-coagulant proteins to prevent clotting and keep the blood flowing,’ he said on the NIH Director’s Blog.

‘But when you cut your finger, for example, you get activation for blood clots in the form of a protein mesh. It looks like a fishing net that can help seal the injury. In addition, platelets in the blood stream help to plug the holes in that fishing net and create a real seal of a blood vessel.

‘Well, imagine it happening in those small vessels, which usually have a non-stick endothelial surface, almost like Teflon, that prevents clotting. Then the virus comes along and tips the balance toward promoting clot formation. This disturbs the Teflon-like property of the endothelial lining and makes it sticky.

‘It’s incredible the tricks this virus has learned by binding onto one of these molecules in the endothelial lining.’

Rapid research set to launch

To investigate the matter further, Professor Monagle is planning two in-vitro studies he hopes will provide crucial information within the next two months on the mechanisms that seem to keep younger people safer, potentially opening the door to directed therapies.

He told Nature that it is possible the virus disrupts communication between the cells, the platelets and plasma components involved in clotting, and that this communication breakdown leads to excess clots forming.

‘If we understand what happens to children, we could tweak adults to make them more child-like,’ he told the journal.

With support from the Doherty and Florey institutes, Professor Monagle and his colleagues will infect cell cultures with SARS-CoV-2 and look for differences in the way the virus affects cells from healthy adults and children, as well as examining how the virus affects cells from adults who have vascular disease.

‘Everyone is treating this empirically or trying randomised trials. What we’re proposing is that if you understand the mechanism by which the virus is causing cells to misbehave – you can then target that mechanism,’ he told newsGP.

To induce these thromboses, the virus would have to cause one (or more) of three issues: abnormalities in the endothelium, in the blood flow, or in the blood itself.

‘We don’t have a prima facie case for blood flow abnormalities, other than as a secondary problem. I think the other two are good places to look,’ Professor Monagle said.

‘If we think about many diseases of adulthood and the burden of disease, they have their origins in childhood. There are much broader reasons for understanding the difference between child and adult physiology at a blood and endothelial level and how the environment and other factors impact it.

‘We’ve seen plenty of infections before that push the endothelium the other way, so it’s not surprising that there’s one virus that pushes it to a thrombotic phenotype.’

What does this mean for treatment options?

According to The Lancet paper by Dr Mehra and colleagues, there is a rationale for therapies to ‘stabilise the endothelium while tackling viral replication, particularly with anti-inflammatory anti-cytokine drugs, ACE inhibitors, and statins’.

Associate Professor Stub said it is a challenge to find medication that significantly boosts endothelial function.

‘However, many of our cardiac drugs such as statins and antiplatelets are thought to have benefits to the endothelium. That would be one area of research,’ he said.

A clinical trial is under way in the UK to examine the efficacy of a new experimental drug aimed at preventing clotting by rebalancing hormones.

Researchers in Sydney are also testing a new drug designed to dissolve blood clots, to augment existing anti-clotting agents.

Log in below to join the conversation.

cardiovascular disease coronavirus COVID-19 thrombosis

newsGP weekly poll

Would it affect your prescribing if proven obesity management medications were added to the PBS?