Feature

Epidermolysis Bullosa, the worst disease you have never heard of

Eliza Baird was born with a rare genetic condition, giving her skin as fragile as butterfly wings. She was one of ‘The Butterfly Children’.

Eliza Baird, who had the very rare skin condition epidermolysis bullosa.

Eliza Baird, who had the very rare skin condition epidermolysis bullosa.

Warning: This article contains graphic images.

All the scans had come back normal. By all accounts the pregnancy was going smoothly.

But when Simone Baird gave birth to her daughter in 2000, it soon became clear something was wrong.

‘Her whole foot was raw, she didn’t have any skin on it whatsoever, and her knee, right down her shin,’ Ms Baird said.

‘She had little bit of skin off the backs of her hand, and her tongue was also affected.

‘She was a … perfect baby in every way, but had missing skin. The paediatrician came in and said, “If I didn’t know any better, I would have said that you tipped boiling water over her”.’

Eliza was rushed off to the Royal Children’s Hospital while the new mother stayed behind at the private hospital, watching other women bond with their babies.

Two weeks later the newborn was diagnosed with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (EB), a severe form of a rare disease where the skin blisters and peels at the slightest touch – the results often likened to third-degree burns.

‘We’d never heard of the disease,’ Ms Baird said.

‘My husband and I are carriers of the same recessive gene and we didn’t know.’

Recessive disorders go undetected as they do not cause any symptoms in the carrier.

For the first six months, Eliza just screamed.

Eliza Baird as a baby in the hospital.

Eliza Baird as a baby in the hospital.

‘She would be in constant pain, she required morning and evening dressing changes including salt and bleach baths which take approximately three hours, three times a week,’ Ms Baird said.

‘Her fingers and toes would web and form strictures, the skin in her throat would become so tight from scar tissue that she wouldn’t be able to eat normal food or at desperate times even be able to swallow her own saliva.

‘She would suffer from corneal abrasions which means her eyes would be closed for three to five days at a time in a darkened room due to a tear on her cornea.’

Eliza’s mobility was affected, she required bandages and dressings all over her body every day of her life and she couldn’t wear normal clothes or undergarments because even the seams on the inside of the clothes would blister her skin.

Through it all, Ms Baird said, her firstborn bore the pain with grace and fortitude.

‘Eliza was amazing, she didn’t let her EB define her,’ Ms Baird said.

‘Even the doctors in the hospital used to say she has got this knack of drawing you in and making you believe she is better than what she actually is. She hid the pain quite well.’

It is estimated that there are around 1000 people in Australia who have some form of EB and over 500,000 worldwide. EB may not always be evident at birth. Milder cases of the condition may become apparent when a child crawls, walks, runs or when young adults become more physically active.

‘Children living with EB are often called “The Butterfly Children” because their skin is as fragile as butterfly wings,’ Ms Baird said.

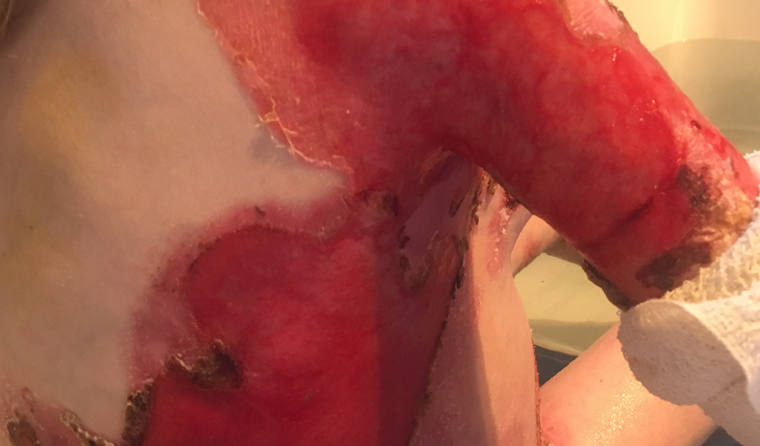

The painful effects of epidermolysis bullosa.

She said the fact that EB is so rare means healthcare practitioners may not even be familiar with the condition.

‘ … So GPs in the local community quite often don’t know what it is, they have never heard of it.’

But people with severe EB often need quite strong pain relief, which can be hard to access through local general practice.

‘For example, my daughter was on methadone among many other things,’ MsBaird said.

‘So you just can’t get that service from a GP … the types of medications for pain relief that these severe EB patients are on, GPs don’t feel comfortable prescribing that.

‘So quite often severe EB patients really need to go through … major hospitals. It would be nice if they could access that support through their local GP.’

Ms Baird said people with EB also often get skin infections and require prolonged antibiotic use, which can be contrary to the current medical practice of limiting antibiotics.

‘My daughter was on antibiotics quite a lot, it made her less sore and the pain was decreased, she could move around. She just felt better in herself,’ Ms Baird said.

‘We used to rotate them quite often so she wouldn’t become resistant to them … I always used to say to the doctors, “For me, it is about here and now and the quality of life. We’ll worry about the rest of it later”.’

Eight months ago, just six weeks short of her 18th birthday, Eliza died due to kidney failure, a secondary complication arising from the condition.

.jpg.aspx)

Simone Baird and her daughter Eliza.

Ms Baird, who has continued her role as a Family Support Co-ordinator with the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association (DEBRA) Australia, an advocacy and support organisation for those suffering from EB, said more research is needed to find effective treatment for the condition.

‘DEBRA’s vision is to have a world where no one suffers from the painful genetic skin condition, EB,’ she said.

‘We are committed to supporting research, which develops innovative treatments, and will one day find a cure.

‘Living with EB changed our life, it changed who we are, but in order to have Eliza with us I wouldn’t change it for the world.’

epidermolysis bullosa genetic disorders rare diseases

newsGP weekly poll

Do you think the Government’s promise to rollout an extra 50 urgent care clinics will place additional strain or negatively impact the already limited GP workforce?