News

How close is a home-grown mRNA COVID-19 vaccine?

The first mRNA vaccine candidate developed in Australia should go to clinical trials next year. newsGP looks into whether GPs will one day administer doses.

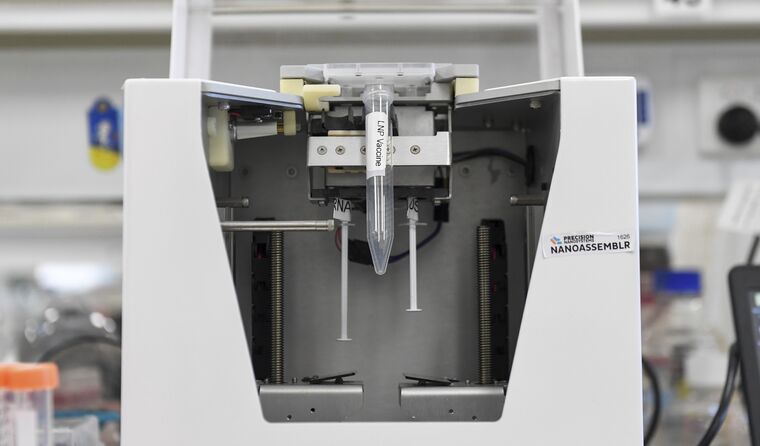

A general view of laboratory equipment at the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Melbourne. (Image: AAP)

A general view of laboratory equipment at the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Melbourne. (Image: AAP)

This week the evolution of a new mRNA COVID-19 vaccine candidate in Victoria captured substantial attention.

It was developed by the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (MIPS) in collaboration with the Doherty Institute and pharmaceutical manufacturer IDT Australia.

Boosted by state funding earlier this year, the first Australian-developed mRNA COVID-19 vaccine candidate has now passed a sterility test, overcoming an important obstacle in its journey towards Phase 1 clinical trials.

It was described as ‘a real watershed moment’ by Professor Thomas Preiss, Leader of the RNA Biology Group in the College of Health and Medicine at the Australian National University.

Associate Professor Archa Fox, a senior lecturer at the School of Molecular Sciences at the University of Western Australia and President of the RNA Network of Australasia also agreed that it is a ‘significant step’.

But with mRNA COVID vaccines already widely available in Australia, how much chance does the current candidate have of featuring in general practice in the future?

Given the current uncertainty, Colin Pouton, Professor of Pharmaceutical Biology at MIPS, is understandably cautious about making any fixed predictions. He calls the pandemic ‘a moving target’ but says the reason for persisting with the program is the possibility the world may need ongoing protection from COVID-19.

‘The reason we’ve kept going with this program is there may well be a need for repeated boosters,’ he told newsGP.

‘If that’s the case, we’re going to need more products made. And if it takes longer to make products than Moderna and Pfizer because of the investment required, it may still be relevant if we need boosters, like we do for influenza, on a regular basis.

‘And of course, the situation changes with commercial interest. If it comes to pass that there is a need for yearly boosters, suddenly you have a lot more companies interested in developing the product.’

Associate Professor Fox also sees the value in being able to produce mRNA vaccines domestically in future, as they can be designed quickly and have proven ‘highly effective at preventing severe COVID-19 disease’.

‘Because of the high cost of buying in vaccine from overseas, and the potential to be at the back of the queue for future pandemics, we urgently need to build expertise, capacity and capability in Australia to make mRNA vaccines and RNA therapeutics more broadly,’ she said.

‘I wish the team the best of luck for smooth progress and good results through the clinical trials.’

Early on in the pandemic, there were three potential mRNA vaccine candidates being developed at MIPS. This has now been narrowed down to one – a candidate that targets the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein.

An application for clinical trials is likely to compare the results of a protein-based vaccine, also being developed in collaboration with the Doherty Institute, which targets the same part of the spike protein.

The Omicron variant identified in the past week has more mutations in the receptor-binding domain than any previous variant.

Professor Pouton believes the vaccine in development could be adapted to counter changes in the virus, although says is still too early to know if the newly identified variant of concern will have the capacity to evade existing protection.

‘Omicron has 15 [mutations] in the receptor binding domain and 10 in the real business end, which is called the binding motif,’ he said.

‘It doesn’t necessarily mean that the vaccines won’t work against it, because it still might look the same.

‘It’s really about whether the antibodies generated, whether they actually still bind to Omicron. And they might, it’s hard to tell.’

Even if the Australian-developed mRNA vaccine candidate does not reach the stage where it is administered into patients’ arms in general practice, Professor Pouton believes the work will remain a notable milestone.

‘It’s very significant in that [the] move from laboratory work to a product for human use is a big step,’ he said. ‘My team had to work closely with [IDT] to try to translate the knowledge that we had into the manufacturing environment.

‘From that point of view, it is a big milestone, because it means that company could make anyone else’s mRNA products, potentially.

‘It just gives people the confidence that the people we have in Australia, in the industry, can make it.

‘I never doubted that. There has been talk [that] we can’t do it, [that it’s] too hard. That was always nonsense.’

Professor Preiss is also excited about the potential.

‘We might well see from this, a new mRNA COVID-19 vaccine come to market,’ he said following the announcement. ‘This alone would be an important development as we are faced with an ongoing demand for vaccines to fight the pandemic.

‘Equally importantly, RNA has plenty of potential as a therapeutic beyond vaccines. The breakthrough in Melbourne then shows us that, as a country, we have the wherewithal to build an RNA [research and development] ecosystem that can efficiently develop these new drugs.

‘The hope now is that we will furthermore put them into local production and service a growing global market.’

Professor Pouton describes the potential broader application of the technology as having a ‘whole host’ of possibilities.

‘Obviously, the advantage of mRNA is the safety,’ he said. There’s no possibility for integration into the genome.

‘So when you’re looking at disease, which is not life threatening and doesn’t need to be corrected permanently, you’re going to be looking at mRNA.’

There are currently 12 COVID-19 vaccine candidates undergoing human clinical trials in Australia, according to the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS).

Two vaccines, Covax-19 (Vaxine) and EDV-plasmid-spike-GC (EnGeneIC), have been created and trialled in Australia, while the others were developed overseas.

In 2020, a vaccine being developed at the University of Queensland reached Phase 1 clinical trials but was subsequently withdrawn due to its potential to interfere with some HIV screening tests.

The Phase 1 clinical trials of the Australian-developed mRNA vaccine and the protein-based candidates are scheduled to be run by the Doherty Institute, with results due in 2022.

Log in below to join the conversation.

COVID-19 Doherty Institute mRNA vaccine

newsGP weekly poll

Would it affect your prescribing if proven obesity management medications were added to the PBS?