News

Is Australia ready for widespread DNA screening?

A new trial is aiming to pave the way for population-level DNA screening, but safeguards are needed to prevent unintended harm.

A study hopes to show that widespread DNA screening should be added to Australia’s screening programs.

A study hopes to show that widespread DNA screening should be added to Australia’s screening programs.

Australia currently has screening programs in place for cervical, bowel and breast cancer.

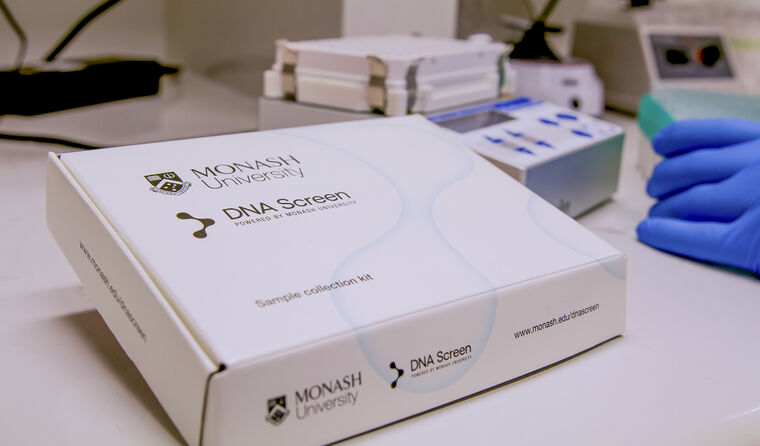

DNA Screen, led by Monash University, is hoping to change this via a proof-of-concept study that will enrol 10,000 Australians aged 18–40 for DNA screening of three hereditary conditions.

As part of the trial, free saliva kits will be sent to participants across Australia to test for 10 known gene variants that can lead to three conditions – hereditary ovarian and breast cancer, Lynch syndrome and familial hypercholesterolaemia.

About one in 75 people, or 1.3% of the population, carries one of these gene variants that can lead to early death and morbidity.

The intention is to show that widespread DNA screening can and should be added to Australia’s screening programs.

Ms Jane Tiller, genetic counsellor, lawyer and co-lead of the DNA Screen, told newsGP there is already a significant amount of public interest.

‘We always thought people would be interested in it and overnight we had thousands of sign-ups. We’ll be oversubscribed,’ she said.

‘Genetic testing has always had preventive potential [but] historically it’s only available for a strong family history or personal history of disease, because costs have been prohibitive.

‘We wanted to sign people up for the single purpose of screening, to mirror screening programs like bowel and breast screening which are government-funded for everybody without criteria, instead of people who had signed up for a research study for other reasons.’

For hereditary ovarian and breast cancer the researchers will test for genes BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2 and ATM.

For Lynch syndrome, which is associated with bowel and endometrial cancer, they will test for MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6, while for hereditary hypercholesterolaemia participants will be will tested for LDLR, APOB and PCSK9.

Although there are many genes that could be studied, the researchers picked these 10 variants for specific reasons.

‘These conditions are medically actionable and there are already preventive measures for them,’ Ms Tiller said.

But while the study aims to mitigate the consequences of severe disease through early intervention, Ainsley Newson, Professor of Bioethics in the Faculty of Medicine and Health at the University of Sydney, told newsGP safe population-wide DNA screening needs to have a defined benefit and the level of tolerance of harm must be reduced.

‘This project signals a big change, taking information that has traditionally been provided individually, for example to someone with a family history and some knowledge of the condition, to the wider population,’ Professor Newson said.

‘We need to be extremely careful that the variants being tested are confidently predictable [for the diseases] in diverse populations.’

Professor Newson points to a recent publication that outlined how hundreds of inherited mutations to BRCA1 were shown to be harmless.

‘We don’t want to provide information that is misleading and can lead to overtreatment and over-testing, both of which can cause harm,’ she said.

‘We need to be extremely careful that the gene variants are confidently predictable for cancer risks.’

DNA Screen will be aimed at well people, equally distributed across Australia to reflect the diversity of age, sex, location and health in a representative fashion.

Participants will also be given options about how their DNA is used in the future. For example, whether their DNA will be made available for future studies related to other health conditions, or if they want their DNA destroyed.

Professor Newson said this could provide an ethical dilemma, as while peoples’ DNA remains more or less the same, knowledge of what this sequence means can change.

It means even though participants will only be tested for 10 genes in this study, if future medical advances find participants to be at high risk of other conditions there may be ethical issues about disclosing that information.

‘As we learn more about the genome, we need to think about what that will mean for the participants in studies like this,’ Professor Newson said.

High risk results uncovered by DNA Screen will be delivered by phone, whereas low risk results will be sent email, with telehealth counselling sessions available for both cohorts.

Participants at high risk will then be referred into public health system if necessary, for example to genetics services. There they would be managed the same way as anyone else at greater risk currently is, for example by colorectal and breast surgeons, cardiologists and other screening clinics.

According to Professor Newson, this aspect of the program could also present problems.

‘We need to think about the utility of this information, not just about the genomic test but the prioritisation of its role in the healthcare system,’ she said.

‘For example, we don’t have widespread dental funding in Australia and there are other basic challenges, such as finding a bulk-billing GP.’

Professor Newson also points out that DNA screening the well population will add more people into the healthcare system, thereby increasing pressures.

‘So it’s fine to offer this information, but we need to make sure it’s thought about in the overall context,’ she said.

Ms Tiller says the DNA Screen team has ‘thought a lot about the harms’, particularly the appropriate care and management for people who may be initially distressed when receiving high-risk results.

‘We minimised the potential harm of over-screening by choosing these 10 genes … because they are known to be high risk and there is a high penetrance – that is, how often someone with the DNA variant will develop the condition,’ she said.

‘We wanted ultimately only people who want this information to sign up.

‘Although people with a high-risk DNA variant can initially experience some distress or anxiety, with good medical support … people express gratitude for the knowledge.’

Should the trial prove successful, the team is hopefully that it will convince government to fund DNA screening in the future.

‘Some companies in the US … offer this kind of testing but the idea of offering it to the whole population for free, underpinned by a public health system, is rare and unique,’ Ms Tiller said.

‘Australia could become the first country to offer preventive DNA testing through a public healthcare system.’

However, Professor Newson cautions that any push towards DNA screening at a population level needs to be carefully designed.

‘Ultimately, anything we can do to encourage and crucially, to support people to care for themselves is important,’ she said.

‘But we need to make sure we can guarantee they have ongoing access to care in the medium-to-long-term.’

Log in below to join the conversation.

DNA Monash screening

newsGP weekly poll

Health practitioners found guilty of sexual misconduct will soon have the finding permanently recorded on their public register record. Do you support this change?