News

Knowing when to discuss issues of sexual trauma

Examining how GPs can broach the subject with patients whose past trauma might be triggered by recent media coverage.

It is estimated that one in six women and one in 25 men have experienced at least one sexual assault since the age of 15.

It is estimated that one in six women and one in 25 men have experienced at least one sexual assault since the age of 15.

Allegations in Australian Parliament of historic rape and sexual assault are receiving significant media coverage and are trending on Twitter.

The #MeToo movement. High-profile billionaires and Hollywood executives. Catholic priests.

The list goes on, and these are just the ones made public.

Meanwhile, sexual assault survivor and Australian of the Year Grace Tame has been praised for her candid approach in leading people to come forward about their experiences of sexual assault, heralding a long-overdue change.

So where do GPs fit when a patient wants to raise – or doesn’t know how to raise – an issue of sexual assault?

Recognised as the most ethical and trusted professionals, GPs are well placed to offer support for such patients.

And even though sexual assault is often the proverbial elephant in the room, GPs can still support those who have experienced it and be advocates to end the silence, according to Associate Professor Laura Tarzia, Deputy Lead of the SAFE program at the University of Melbourne. She said GPs need to be aware of the signs.

‘GPs should always have this on their radar,’ Associate Professor Tarzia told newsGP.

With recent news events potentially triggering trauma of past sexual assault experiences, Associate Professor Tarzia said what is often not realised is the fact sexual assault and violence is more commonly perpetrated by intimate partners.

‘GPs need to be aware that this is probably the most common presentation,’ she said.

‘Even though we’re reading at the moment about what’s going on in Parliament in a work-based context, and [there are] lots of people coming forward on social media disclosing experiences, actually the most silenced type of sexual assault is what happens in intimate relationships.’

Associate Professor Tarzia said it is important for GPs seeing patients who have disclosed other types of violence to also ask about sexual violence, because it’s ‘just so common’.

‘Even if someone discloses that physical or psychological abuse is happening in a relationship, they may not actually voluntarily disclose the sexual violence,’ she said.

From a study conducted in Australian general practices looking at the prevalence of sexual violence, Associate Professor Tarzia found that just under half of the women who attended the clinics over the study period and participated had had some kind of experience of sexual violence during their adult life.

‘It’s really prevalent in general practice, because of course we know all the health effects that even historical sexual violence can have and how those effects linger on and on after the experience itself,’ Associate Professor Tarzia said.

‘GPs are seeing people who might be presenting with unexplained headaches, mental health issues that don’t seem to go away. So they’re really well placed to be able to find out further about other things that might have happened for that woman in the past, or of course men, but primarily it is going to be women.’

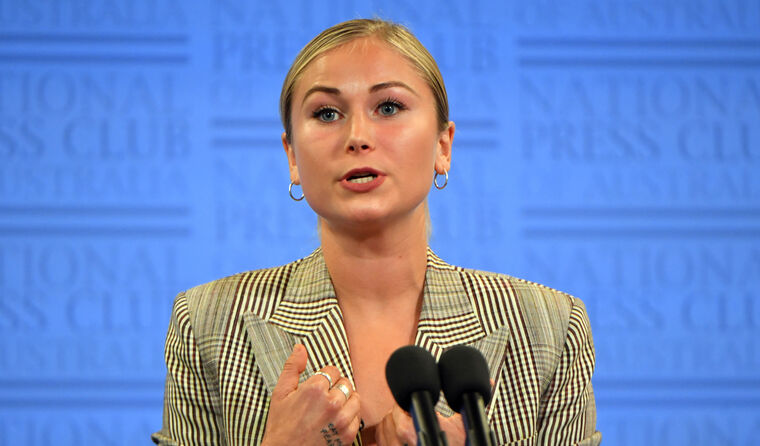

Grace Tame has been recognised as an advocate for sexual assault survivors after speaking out about her own experience. (Image: AAP)

Grace Tame has been recognised as an advocate for sexual assault survivors after speaking out about her own experience. (Image: AAP)

Building on recommendations from the RACGP’s White Book, for which she is author of the updated chapter on sexual assault, Associate Professor Tarzia recommends asking questions that are not too confronting and giving the patient space to disclose, if they choose to do so.

For example, ‘Sometimes things that have happened in the past can continue to affect us even now. I see a lot of women who may have had an unwanted sexual experience in the past, do you think that may have been going on for you?’.

Although it may take a few visits to the GP before the person feels comfortable to talk about their experience – the same as with any abuse or violence – it is important the right atmosphere is created.

‘If GPs are mindful that if someone discloses [their sexual assault experience] they are not going to be judged,’ Associate Professor Tarzia said. ‘But most importantly, they are going to be believed, and any support provided is meeting the individual patient’s needs.’

Associate Professor Tarzia was a co-author of a recent qualitative study published in BMJ Open that tracked the results of women’s engagement with health practitioners following experiences with intimate-partner violence.

She found women most wanted to feel like someone cared about what was going on for them.

‘It is really quite simple for a GP or another health professional to just do something really basic like handing them a box of tissues, or another simple gesture,’ she said.

‘Although the review was of intimate-partner violence experiences, we noticed so much crossover with sexual assault, so it’s going to be very similar for patients who have been sexually assaulted.’

Aligning with the World Health Organization’s LIVES pneumonic: Listen, Inquire about needs, Validate experiences, Enhance safety, Support and follow up, the study review team came up the CARE model:

- Choice and control

- Action and advocacy – eg linking patients with other services, or just being a person to talk to

- Recognition and understanding – of the dynamics of what goes on when someone is sexually assaulted, eg that it may not be a stranger but an intimate partner

- Emotional connection

‘It’s about how you support patients, and those principles of person-centred care are the same,’ Associate Professor Tarzia said.

‘GPs should not be scared to gently enquire about patients’ past experiences of sexual violence because with some very simple communication and emotional intelligence skills, it’s possible to provide really effective support.’

It is

estimated that one in six women (17%) and one in 25 men (4.3%) have experienced at least one sexual assault since the age of 15. Particular groups are at greater risk, including young people, those with disability, and people who have previously experienced abuse.

The White Book

states that as many assaults go unreported, the effects – both physical and psychological – may go untreated.

Associate Professor Tarzia believes this could be because sexual assault is more common among intimate partners.

‘It is associated with worse mental health, because there’s whole lot of background stuff going on as well. Not just the trauma of the event but often it’s something that is repeatedly perpetrated over years and years, living with the perpetrator,’ she said.

‘It’s very traumatic and harmful, and people just don’t talk about it for a whole lot of reasons, [such as] taboos around sex [or] the fact that people don’t consider it to be rape when it’s a partner.

‘Sometimes sexual assault is not spoken about as much as intimate partner violence in terms of GPs and health practitioners more broadly, so I’m really pleased that it’s getting more attention at the moment.’

The White Book is currently being updated, with the fifth edition scheduled for release in 2021.

Log in below to join the conversation.

intimate partner violence sexual assault sexual violence White Book

newsGP weekly poll

Health practitioners found guilty of sexual misconduct will soon have the finding permanently recorded on their public register record. Do you support this change?