News

Relapse reports ‘don’t undermine Paxlovid capability’

Rare cases of COVID-19 rebounding after patients have taken a course of the new oral antiviral treatment have been widely reported.

Reports of viral ‘rebounds’ following treatment have been widely circulated.

Reports of viral ‘rebounds’ following treatment have been widely circulated.

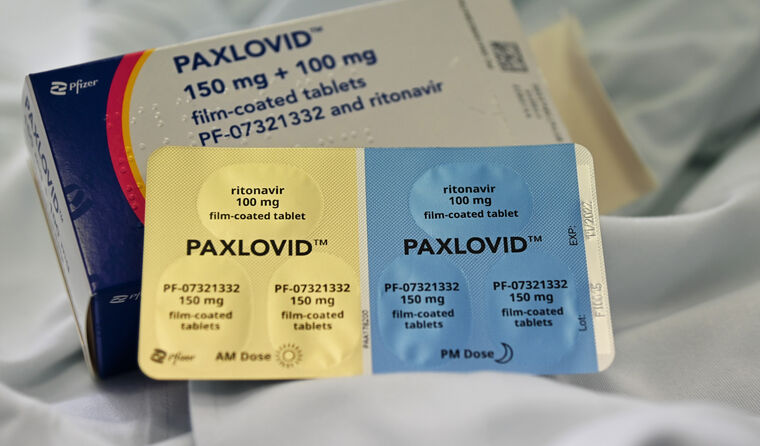

One of a suite of new treatments designed to limit the impact of COVID-19, nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir, sold as Paxlovid, became available on the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS) this month.

Along with another oral antiviral treatment, molnupiravir (sold as Lagevrio), it is now stocked in pharmacies around the country as part of a national approach for managing the disease in the community and preventing more severe illness.

In recent weeks, however, reports of viral ‘rebounds’ following treatment have been widely circulated. These have particularly been highlighted in the US, where the treatment has been approved since the end of last year, and the country’s government has invested in enough supply to treat around 20 million people.

Do these cases have implications for prescribers in Australia?

For infectious diseases physician and microbiologist Associate Professor Paul Griffin, the reports are a part of an evolving understanding of the treatment – but should not affect the current clinical approach.

‘What this doesn’t change is the fact that the drug has certainly been proven in those unvaccinated high-risk people to reduce their chance of progressing to severe disease,’ he told newsGP.

‘These reports certainly don’t undermine its capability in that regard at all.’

In fact, the occurrence of a viral ‘rebound’ was observed in a small number of cases (between 1–2%) in the first clinical trials, which found the treatment reduced the risk of hospitalisation and death among at-risk groups by 89%.

Both Pfizer, the developer of the treatment, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), have pointed out that the recurrence of positive tests was observed to a similar degree in the placebo group of the first clinical trials.

They also both suggested no conclusions could be drawn about whether the treatment caused the rebound.

Dr John Farley, the FDA’s director of the Office of Infectious Diseases, said more work has taken place due to the reports and that even in patients who have recurrences, there is no increased cause for concern.

‘FDA is aware of the reports of some patients developing recurrent COVID-19 symptoms after completing a treatment course of Paxlovid,’ he stated on the regulator’s website last week.

‘In some of these cases, patients tested negative on a direct SARS-CoV-2 viral test and then tested positive again.

‘Additional analyses show that most of the patients did not have symptoms at the time of a positive PCR test after testing negative, and, most importantly, there was no increased occurrence of hospitalisation or death or development of drug resistance.

‘These reports, then, do not change the conclusions from the Paxlovid clinical trial which demonstrated a marked reduction in hospitalisation and death.’

Dr Farley also said there is no evidence for prolonging the treatment nor for giving a repeat course in patients whose symptoms reoccur.

It is an approach that makes sense to Associate Professor Griffin given what is known so far.

‘The implications of extending the course are not insignificant,’ he said.

‘Not only would we have fewer doses to use, so potentially fewer people would get that benefit that we know that it has, but there are also obviously risks of toxicity with extending that course out.

‘It’s certainly not a recommended course of action at the moment.’

Health officials have flagged that Paxlovid may be utilised across more patient populations as COVID becomes endemic, depending on availability. (Image: AAP)

Health officials have flagged that Paxlovid may be utilised across more patient populations as COVID becomes endemic, depending on availability. (Image: AAP)

The head of the TGA, Adjunct Professor John Skerritt, has previously underlined the practical challenges in collecting efficacy data for the new oral antiviral treatments.

Last month, he pointed to the lag in detailed evidence emerging about vaccine efficacy, and said he believes it will take around the same timeframe before a more detailed understanding of the impact of the oral antivirals is gained.

However, Professor Skerritt also said the treatment could eventually be applied much more widely than it is currently.

‘With endemic COVID, we could well see ourselves in a position where these drugs are very widely available in six or 12 months’ time and we don’t need to limit to people with co-morbidities,’ he said.

‘If the drug prevents the progression of disease in someone with co-morbidities, it would be hard to imagine that it wouldn’t also prevent viral replication in someone who doesn’t have co-morbidities.’

Following the recent recurrence reports, some experts have expressed concerns that nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir might not be strong enough to suppress virus altogether and could potentially give rise to drug-resistant mutations.

But Associate Professor Griffin says those concerns are only theoretical.

‘We want to make sure that we’re not driving further mutations,’ he said.

‘The laboratory data that we have, and the understanding of the mechanisms of action, is that it seems unlikely that use of these drugs will drive further mutation.

‘The virus is doing a good job of doing that by itself already, and the best way of addressing that, of course, is to have as many people vaccinated globally as possible.’

He also believes there is much yet to be discovered about the treatment’s potential.

‘The research into showing its capabilities is ongoing – pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis, for example, all those sorts of studies.

‘It’s a drug with a lot of potential and a really good mechanism of action, so we certainly want to study it in as many different indications as possible.

‘But until we have that data to confirm that it’s effective, we certainly don’t want people to be using it outside of how it’s approved at the moment.’

A recent announcement by Pfizer suggests the treatment may not do much to stop close contacts of confirmed cases from contracting the virus – although there was not enough evidence to draw conclusions over its impact on the severity of illness.

With the initial clinical trials having taken place among unvaccinated people when the Delta was dominant, Pfizer is currently carrying out a large, ongoing study into the effects on at-risk vaccinated people, the AP news agency reports.

Who is eligible?

According to PBS criteria, the drug can be prescribed for those with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 confirmed by a PCR or rapid antigen test within five days of symptom onset, among the following patient groups:

- Those aged 65 or older, with two other risk factors for severe disease

- Those aged 75 or older with one other risk factor

- Those aged 50 and older who are of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin with two further risk factors for severe disease

- Those with moderate-to-severe immunocompromise

The RACGP’s COVID-19 resources includes information relevant for every state and territory.

A guide with details relevant to general practice about the COVID-19 oral antivirals has also been published by newsGP.

Log in below to join the conversation.

COVID-19 nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir oral antivirals Paxlovid

newsGP weekly poll

As a GP, do you use any resources or visit a healthcare professional to support your own mental health and wellbeing?