News

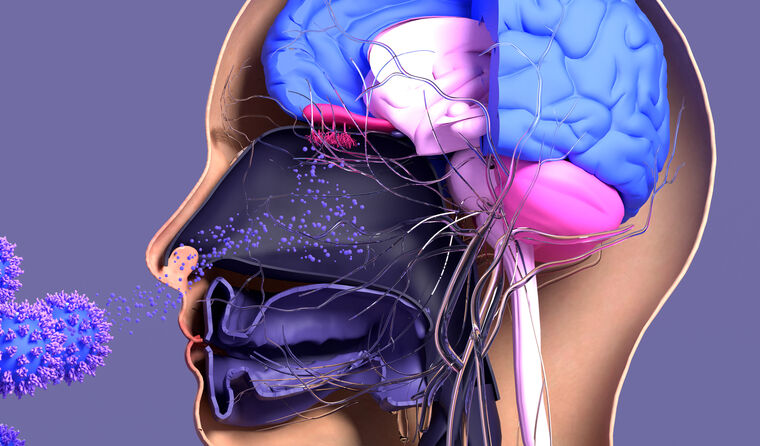

Research suggests COVID affects brain even in milder cases

Authors say more work is needed to establish the biological mechanism causing changes to the brain, as well as the longer-term impacts.

Findings from the news study identify that long-term effects of COVID-19 on the brain are ‘not to be taken lightly’.

Findings from the news study identify that long-term effects of COVID-19 on the brain are ‘not to be taken lightly’.

A study comparing before and after MRI scans of COVID-19 patients suggests parts of the brain can be affected an average of 20 weeks after infection is diagnosed.

The peer-reviewed paper, set to be published in the scientific journal Nature, used two separate brain scans of 785 individuals taken from the biomedical database UK Biobank.

The research included 401 cases who tested positive to the virus in between scans and 384 control cases who had no positive test during the study.

The authors say that using brain scans taken prior to infection reduced the risk of pre-existing conditions being interpreted as linked to COVID-19 disease.

They also say they adjusted for potential confounding factors. Even after those calculations, the researchers found ‘significant effects’ associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

This includes a steeper reduction in grey matter thickness in the areas of the brain linked with smell and memory, including the orbitofrontal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus and the olfactory cortex.

Professor Trichur Vidyasagar, Head of the Visual and Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Melbourne, said the study’s findings are important.

‘Despite the various challenges that inevitably lead to some shortcomings, this is as good a study as is possible to evaluate the effects over time of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the brain after supposedly “recovering” from COVID-19,’ he said.

‘The existence of baseline data prior to the pandemic has been a boon that the authors have leveraged brilliantly.

‘The study suggests that long-term effects of COVID-19 on the brain are not to be taken lightly even in those with milder disease who did not need hospitalisation during the acute illness.’

Professor Vidyasagar also said it remains to be seen whether the impact of the observed changes would deteriorate or whether the brain’s capacity for plasticity would help recovery.

Aside from damage to the brain in areas linked with smell and memory, researchers also found a small reduction in whole brain sizes for those infected by SARS-CoV-2.

Cognitive tests that were carried out as part of the research indicate those diagnosed with COVID-19 had a steeper cognitive decline on average between their scans.

Even when excluding the 15 patients in the COVID-19 group who were hospitalised, differences remained between those who had been infected and the control group.

However, researchers note the structural brain differences ‘are modest in size’ and say there is not yet enough evidence to establish the long-term impacts.

‘Whether these abnormal changes are the hallmark of the spread of the pathogenic effects, or of the virus itself in the brain, and whether these may prefigure a future vulnerability of the limbic system in particular, including memory, for these participants, remains to be investigated,’ they write.

No further information is available on the severity of the COVID-19 cases in the cohort included in the study, apart from the data on hospitalisation.

The age of the participants varied ranged from age 51–81, with the brain scans taking place an average of 38 months apart. For the group with a positive COVID-19 test, there was an average of 141 days between diagnosis of the disease and the second scan.

Study authors also suggest the impact is more pronounced among older COVID-19 patients, but point out that not everybody in the study diagnosed with the disease was affected.

The researchers from University of Oxford, University College London, and Imperial College, as well as the National Institutes of Health in the US, carried out their work before the emergence of the Delta and Omicron variants.

No information is available on the strain of infection involved with the study cohort, which included infections ranging from March 2020 to April 2021. The authors state that a small number of participants are likely to have had the original strain, while the majority probably had subsequent variants of concern – mostly Alpha, but also Beta and Gamma.

Other shortcomings of the research identified by the authors include limited evidence on the effects on different ethnic groups, and the fact that infection status was identified for some cases through rapid antigen tests with varying degrees of accuracy.

There was also no information on vaccination status and how vaccination dates fit in with infection.

However, Professor Rob Hester, a researcher in cognitive neuroscience and Head of the University of Melbourne’s School of Psychological Sciences, called the study ‘rigorous in its methodology’, and said it had controls for thousands of confounding variables.

‘The study provides strong evidence of a subtle reduction in brain size, ranging from 0.2–2%, particularly in frontal and temporal brain regions important to cognitive abilities such as self-control and memory,’ he said.

‘For comparison, adults in the sample age range would usually show reductions of 0.2% per year.’

Professor Hester said the brain changes were not linked to declines in cognitive performance overall, despite the study showing a subtle decline observed in speed of thinking. He said that would be ‘of a level that would be unlikely to affect everyday function or potentially be noticed’.

Nonetheless, Dr Sarah Hellewell, a research fellow at the Perron Institute for Neurological and Translational Science, said the study could have implications for Australia.

‘These findings may also apply to Australians, but people need not panic if they have had COVID-19,’ she said.

‘The brain changes observed were relatively small and on a group level, so not everyone had the same effects.’

Late last year, the RACGP updated its guidelines on looking after adults with post-COVID-19 conditions.

Log in below to join the conversation.

brain COVID-19 long-COVID neurology

newsGP weekly poll

How often do patients ask you about weight-loss medications such as semaglutide or tirzepatide?