News

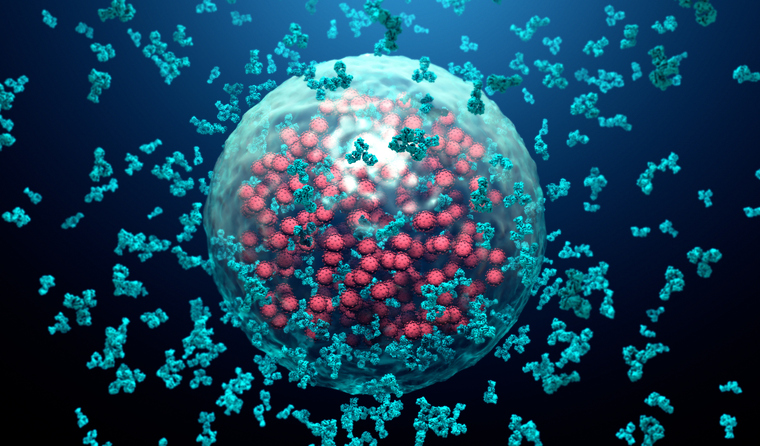

T cells provide long-lasting immunity against COVID: Study

According to new Australian research, the T cell response to COVID-19 lasts for at least 15 months.

A third dose of a COVID-19 vaccine re-activates T cells, bringing the levels back up again, Dr Jennifer Juno says.

A third dose of a COVID-19 vaccine re-activates T cells, bringing the levels back up again, Dr Jennifer Juno says.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues into its third year and Australia sees an uptick in new infections, the conversation around immunity – either from vaccination or post-infection – is once again front of mind for many.

Now research, published in Nature Immunology, provides new insight and hope about the role of T cells in fighting infection.

Led by researchers at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, the study has revealed that the body’s T cells, once activated through either vaccination or infection, have a long-lasting memory against COVID-19 for at least 15 months.

The team tracked the T cell responses of 29 people – 21 who had recovered from a primary infection that resulted in mild illness over the course of more than a year, and nine who had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine over seven months.

But despite not following the two cohorts for the same amount of time, they did note a similar pattern, with an initial contraction of the immune response immediately following exposure – either through infection or vaccination – followed by a stabilisation of T cells at six months.

For those who had been infected, T cells remained level and capable of recognising the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein after 15 months.

Co-author of the paper, Dr Jennifer Juno, a Research Fellow at the Doherty Institute, says even though some parts of the immune response do wane, it is now clear that T cells that can recognise the virus are ‘quite stable over time’.

‘It was really nice to see how long lasting those cells were,’ Dr Juno told newsGP.

‘It was really, really striking when we started looking at that longitudinal data and saw that between six and 15 months how stable those frequencies were, and that we could still detect them in every single person that we were looking for.

‘After more than a year, they were still roughly 10-fold higher than someone who had never been exposed to the spike protein through infection or vaccination.’

While research focused on the role of T cells in protecting people against the effects of COVID-19 is growing, the overwhelming focus has been on B cells, which are responsible for producing the antibodies that recognise SARS-CoV-2.

However, T cells play a crucial role in supporting the development of the B cell response.

As booster uptake in Australia lags, with just 66.7% of the eligible population having received more than two doses, the research has also provided further insight on the importance of vaccination, including booster doses.

The team found that when participants were re-exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein through vaccination, the T cells quickly reactivated and increased in number, generating levels up to 30 times higher than they were prior to vaccination.

Dr Juno said that in general, they found that vaccines generate the same amount of T cells as those found in individuals who had been infected.

‘We also saw that the third dose does an incredible job at re-activating those T cells and bringing the levels back up again,’ she said.

Asked whether the emergence of variants of concern such as Omicron are likely to have much of an impact on reducing the T cell response, Dr Juno said she expects any impact to be ‘much less’ than is seen with the B cell response.

‘In our particular study, we were looking at a very specific portion of the spike protein, and that portion is not different in Omicron compared to the original virus, so it’s quite conserved,’ she said.

‘But, in general, because there are a lot of different areas of the spike protein that the T cells can recognise, they don’t take that hit the same way that the antibodies take when there are different variants.

‘I think that’s really been something that people are quite interested in understanding, how T cells might come into play in terms of longer-term protection, given how the virus is changing over time.’

While it is still early days in determining the need for a second COVID-19 booster, or fourth dose, early data from Israel suggests the benefit may be only marginal for young and healthy people compared to a third dose.

Dr Juno says if that if remains the case, there will be a push to consider which populations are likely to benefit the most from ongoing boosting.

The research, conducted in collaboration with the laboratory of Professor Miles Davenport from the Kirby Institute, utilised new technology – referred to as tetramers – which help to identify which T cells recognise the spike protein.

According to Dr Juno, this technique results in more accurate findings.

‘Usually we have to stimulate the cells in the lab before we can measure the T cell response,’ she said.

‘However, using tetramers, we can look at them straight from the blood samples, meaning we are getting a more accurate picture of what is happening.’

The authors note that with vaccine effectiveness showing signs of decline in many countries, and with the emergence of variants of concern such as Omicron evading neutralising antibody responses, the likely importance of memory B and T cell recall in preventing severe illness following breakthrough infection is emphasised now more than ever.

To find out more, the team has now turned its attention to learning about the role of T cells and how they react in people who have been vaccinated with either two or three doses and experience a breakthrough infection with Delta or Omicron.

‘We’re interested in trying to understand how quickly the immune system actually can reactivate once you have an infection, and trying to identify which components of the immune system might be most important for controlling that virus and for keeping any breakthrough infections to be mild,’ Dr Juno said.

‘So it’s a difficult question to answer, but we’re hoping to get some insights from longitudinally studying individuals who have breakthroughs.’

Log in below to join the conversation.

boosters COVID-19 Omicron T cells vaccination

newsGP weekly poll

How often do patients ask you about weight-loss medications such as semaglutide or tirzepatide?