News

The high cost of brain injury as a result of family violence

A landmark new report from Brain Injury Australia shines a light on family-violence-related brain injury, and points to a pathway for diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation.

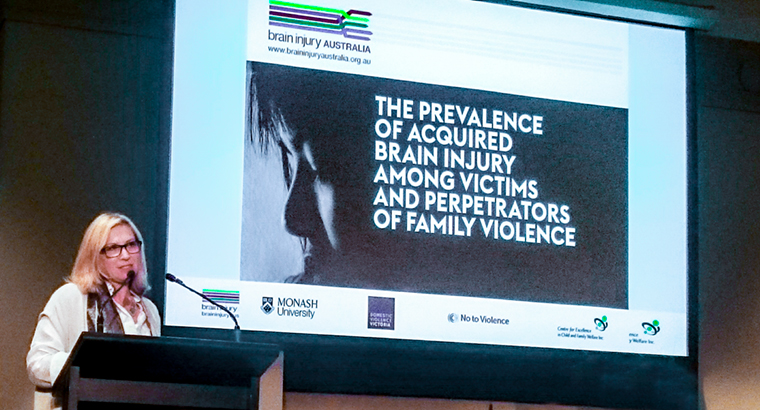

Rosie Batty, 2015 Australian of the Year, speaks at the launch of Brain Injury Australia’s new report.

Rosie Batty, 2015 Australian of the Year, speaks at the launch of Brain Injury Australia’s new report.

The Brain Injury Australia report, ‘The prevalence of acquired brain injury among victims and perpetrators of family violence’, said to be the first of its kind in Australia, was launched at the Melbourne Town Hall by Rosie Batty, 2015 Australian of the Year and Chair of the Victorian Government’s Family Violence Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council.

‘The extent of what victims of family violence have to experience continues to shock; there are so many more layers of complexity and horror,’ Ms Batty said at the report launch.

‘It’s really important that these kind of reports are able to give substance, credibility and proof of evidence of what needs to change – and so much needs to change. Not just for those who are victims of this violence, but also those who are perpetrators.’

The report contains many sobering statistics: 40% of Victorians attending hospital for reasons of family violence had sustained a brain injury. Thirty one percent of this 40% were children under the age of 15, and one in four of these children had sustained a brain injury.

The economic consequences of family-violence-related brain injury are high, with the Brain Injury Australia report estimating costs in Victoria of $5.3 billion in 2015–16 alone. But the personal costs to victims are incalculable and range from inability to leave a violent relationship due to impairment of functions, such as planning and cognition, through to severe disability or even death.

The research also found a strong association between brain injury and the perpetration of family violence, with those who perpetrate family violence twice as likely to have sustained a brain injury.

‘To say that there is an association between TBI [traumatic brain injury], behavioural disability and offending is now not only undeniable, but uncontroversial,’ Nick Rushworth, Executive Officer of Brain Injury Australia, said at the launch.

Research was also conducted among healthcare practitioners, revealing gaps in knowledge about risk of brain injury as a result of family violence, as well as how to recognise and diagnose the disability.

One practitioner told researchers, ‘I’ve worked with a lot of women who have had facial injuries and head injuries but … I never thought about, is there a brain injury there? I think number one is knowledge of a brain injury and how it occurs, and then of good partnerships with services that can work towards [diagnosis and follow-up care]’.

Mr Rushworth told newsGP he would like to see further training in this issue for GPs, who he believes are often a lynchpin in the care of patients experiencing brain injury as a result of family violence.

‘People who have a severe head injury are beautifully catered for by state-of-the-art, best practice acute care,’ he said. ‘But for those individuals sent home by the hospital, their next port of call is usually their local GP.

‘So helping GPs to recognise post-concussion syndrome with mild traumatic brain injury is absolutely crucial.’

It is the ultimate hope of Brain Injury Australia that its report can help point a way forward in the treatment of people experiencing brain injury as a result of family violence, as well as rehabilitation for people who use family violence.

‘These people need help, and they need help early,’ Ms Batty said.

RACGP resources

In addition, Australia’s health ministers

agreed at April’s Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Health Council to provide funding to the RACGP for the development of further training materials and resources.

abuse-and-violence brain-injury family-violence white-book

newsGP weekly poll

Which of the following areas are you more likely to discuss during a routine consultation?