Feature

‘The system let him down’

One mother shares the story of her son who died aged 26 from long-term effects of alcohol, saying there were failings in the health system to connect him with appropriate care.

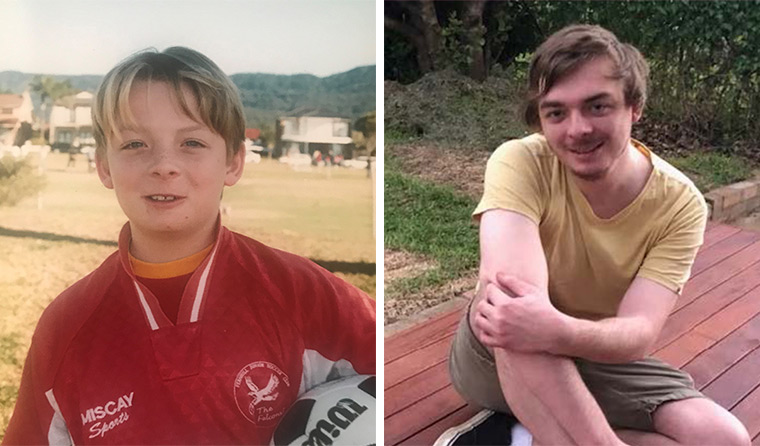

Dylan Allen as a boy, and on Christmas Day 2021, less than four months before he died. (Images: Supplied)

Dylan Allen as a boy, and on Christmas Day 2021, less than four months before he died. (Images: Supplied)

‘I hope our story will change how GPs treat and manage this disease. It has the potential to save a lot of young people who are often overlooked due to their age.’

Rachel Allen’s son Dylan was just 26 years old when he died in April 2022 of end-stage liver disease caused by alcohol dependence.

Now, Rachel wants to share her family’s story in the hope it has an impact and influences change by raising awareness of the harms of alcohol and the need for improving links between healthcare providers.

‘It’s so complex and multi-layered,’ Rachel told newsGP.

‘This isn’t about blame because I don’t find that constructive, but it is more about speaking the truth and being transparent around how things went wrong.’

Dylan began drinking alcohol around the time he turned 17 years old, and while his mum was there to support him, continuity of appropriate care services was challenging.

‘There were a lot of different people involved across different departments, whether it be mental health, community health, GPs, or his private hospital that he used to go in and out of, and none of them linked up,’ Rachel said.

‘There was no collaboration or multidisciplinary team care. Maybe if he’d been on the NDIS in any kind of capacity, there would have been more of a trail of information.

‘I would like to prevent it getting to that stage for others who have been drinking as prolifically and for as long as he had, and had as many complex, mental health needs as he did.

‘Ideally if some sort of medical and mental health database could be created that provides all the relevant information at the click of a button then we could establish some continuity of care and doctors could make more appropriate decisions based around that information.’

Despite Rachel trying to convince him otherwise, Dylan refused to be on the NDIS because he felt he did not need it, that it did not apply to him, despite his underlying mental health issues, namely severe anxiety in the form of panic attack disorder and severe depression.

‘His anxiety attacks could just come from nowhere, but often it was socially linked,’ Rachel said.

‘Dylan had suffered from social anxiety for years which profoundly impacted on his capacity to mix with people.

‘This again is what made things so complex because, as you could imagine, the anguish he went through just at the thought of going into a huge rehab for months not knowing anyone.

‘Dylan genuinely wanted to be able to do it but his social anxiety made it impossible for him … because he was so fearful of those places.

‘I tried to come up with a compromise because I was desperate. I also want to point out that this wasn’t because he was deliberately being difficult but was based on genuine fear.

‘He was extremely judgemental of himself and had such low self-worth that he assumed everyone felt the same way about him.’

Barriers to essential care

Eventually Rachel linked her son up with the South Coast Private Hospital in Wollongong, where over the years he went in and out across around 13 admissions in what she describes as an ‘almost impossible task’ after years of drinking.

The hospital stays, although they offered him a break from drinking and gave his liver time to detox, were not a long-term solution. Rachel said there was very little time spent with the psychologist, thus very little time spent discussing the issues associated with his drinking.

Therefore, after doing a detox and short three-week program he would be discharged feeling better but would then go home to the same feeling that nothing had changed in his life. There was no follow-up care – which made staying sober a relatively unlikely outcome.

‘He still had that self-loathing, he had no way of getting all these very self-deprecating negative thoughts out of his head other than to deal with it with alcohol,’ Rachel said.

‘Alcohol became his only way to numb his destructive and negative thoughts. By the age of 24 it became apparent that Dylan was severely addicted and therefore the probability of him being able to give it up was becoming less likely.’

Knowing this was the case, his psychiatrist at one stage put Dylan onto Antabuse, a very strong medication that can make people unwell if they drink while taking it.

Rachel said at this time he was able to stay sober the longest which she remembers for a period of five months.

‘I feel to this day if he had more supports in place at this time he would have stayed sober, but unfortunately he was mostly relying on me at the time,’ she said.

‘The mental health system was not linked up to try and support him and the psychiatrist he had was mostly interested in providing him with his medication.’

Improving care

‘Thinking back there was one GP who stood out over that six-year timeline of Dylan drinking and he had tried to work on Dylan reducing his alcohol intake,’ Rachel recalls.

‘The complication around this is it wasn’t something that could be monitored and when you are so severely addicted to alcohol you don’t have the self-control to do this.

‘It’s not about making excuses for his drinking, but conversely it’s about highlighting the facts around why this approach just doesn’t work in these more serious cases of addiction.

‘It’s about trying to come up with better ways to manage it, so that we have more successful outcomes for people who have such complex needs.’

Dr Hester Wilson is Chair of RACGP Specific Interests Addiction Medicine, and although not Dylan’s GP, is a long-time advocate for harm minimisation and reducing stigma in this space.

She told newsGP that as alcohol use is common, GPs often encounter it in their practices, and the huge impact it can have on people’s health and wellbeing needs to be flagged more.

‘As GPs we have a pivotal role, providing preventive and early intervention messages for people drinking alcohol,’ Dr Wilson said.

‘We can encourage lower risk use with two standard drinks a day to decrease long-term harm and less than four standard drinks a day for acute harm.

‘Every moment matters. Dylan had severe alcohol dependence; he was so young, and his death is a tragedy. I applaud Rachel for her tireless advocacy to ensure this doesn’t happen again.’

Rachel believes there is a huge gap in clear understanding about what alcoholism does to the brain, and how it effects people’s decision-making and lifestyle. She is particularly calling for raised awareness on the harms drinking can have on young people, like her son.

‘The younger you start, the more likely you are to develop long-term hazardous drinking and then die from cirrhosis – that’s why intervening at a very young age is so critical,’ she said.

‘For Dylan drinking from an early age, the neuro pathways in his brain were already starting to change right through that critical time when his brain was still forming, and it caused a whole lot of problems for him trying to navigate how to get out of this situation, because his brain itself had been so vastly affected.’

For the last few years of his life, Dylan hardly went outside and he relied on his mum to buy his alcohol.

‘To this day I hate that I was put in that position,’ Rachel said.

‘I still have a lot of guilt associated with this. However, by this stage his addiction was so bad that ironically without alcohol he would most likely die. I remember going into the BWS [bottle shop] and thinking, “how did it ever get to this stage?”.’

As his condition deteriorated his mum was by his side the whole time.

On the day before he died, Rachel took a photo of Dylan partly to help raise awareness of the long-term impacts of alcohol use on someone of such a young age.

In his final days, Dylan’s skin was extremely jaundiced from liver failure. (Image: Supplied)

In his final days, Dylan’s skin was extremely jaundiced from liver failure. (Image: Supplied)

‘I recall looking at his face and thinking, “this isn’t right – he had his entire life ahead of him”,’ she said.

‘I want this picture to be out there for people to know that from a really young age heavy drinking can have such a detrimental and deadly affect.’

The value of therapeutic relationships

Towards the end of Dylan’s life, Rachel tirelessly worked with numerous healthcare services to get the most appropriate care for her son’s acute needs. But she was met with red tape challenges and attached stigma.

‘His GP tried twice to admit him to a mental health facility where he would have probably got all services piled on thick, but he was turned away … and I think it was because of his drinking,’ she said.

‘That’s why I think they don’t like to deal with people who have any addiction in mental health. It’s still stigmatised, but more complicated, because he needed a detox. He could have easily just gone into a detox at the hospital, then come out to deal with his mental health, but it’s complex and they didn’t want to admit him.

‘He told me how scared he was when they tied him down and sedated him, but he was still released in that condition.

‘But I was surprised, because his GP actually had tried to initiate that. His GP could not believe that his request for immediate admission was dismissed. This GP at the time really had tried to help Dylan but it demonstrates the extent to which the mental health system is extremely inefficient at times.

‘We will never know how Dylan would have gone had he been admitted by his GP. I as his mother feel that he would have received the mental health care he needed at the time and may not have had to return to drinking.

‘I know there’s conscientious GPs out there who really want to do the right thing by these people … but there just seems to be a lack of training in this area.’

Dr Wilson, who is a strong advocate for eliminating stigma associated with addiction, said the GP–patient relationship should not be underestimated.

‘For those who have high level risky, harmful or dependent alcohol use, we can assist people to undertake behaviour change including alcohol withdrawal,’ she said.

‘We can manage mild dependence with the assistance of our local pharmacist and support and encourage referral to specialist alcohol and other drug (AOD) settings for withdrawal management.

‘Integral to our role is the ongoing support and medication management for alcohol dependence including relapse prevention medications, and medications and lifestyle changes to support healthy liver and liver recovery.

‘As GPs we need to screen for liver disease, undertake comprehensive assessment and investigations and support specialist review.’

The RACGP’s November unit of check focuses on AOD, and includes GP clinical cases on alcohol withdrawal management, and support for family and carers of people using AOD. The Red Book has screening guidelines for mental health and AOD use.

Fighting for change

After Dylan died, a grieving Rachel decided to continue the fight to raise awareness of not only the devastating harms of alcohol dependence, but the lack of continuity and holistic care for people experiencing it.

‘We never were prepared for him to die. But he was well looked after by his family even though there was a lot he couldn’t do for himself,’ Rachel said.

‘It was evident from when he went into ICU, that because he was on life-saving equipment he wasn’t going to make it unless he had a liver transplant.

‘There’s all this controversy around liver transplants for alcoholics, but one day, I’d like to investigate that even further, because that still seems very discriminating.

‘The way they came so quickly to the conclusion at the hospital that Dylan would not receive a liver was so devastating. They completely based this on his history of drinking and did not consider the fact for once that with a new liver and supported care, he may have turned his entire life around.

‘In the US they now recognise this and are transplanting livers to people with alcohol hepatitis. They look at the young life in front of them instead of the addiction.’

In Dylan’s case there were lots of missed opportunities, and Rachel often thinks her son can be an example to so many people, and to improve the system.

‘Because I was proactive, he was actively trying too for a long time to get better, and in my mind, he should never have died,’ she said.

‘We have one of the best health systems, but we have to question, why did he die? That should not have been the end result, so it’s worth looking under a microscope to find out why, and what went wrong, and learning from Dylan’s experience.

‘The health system really let him down.’

Rachel says that when Dylan presented at a GP in February of 2022, he was in an acute state of liver failure, but he was not triaged as if he was.

‘If he came in with failing kidneys and wasn’t an alcoholic, I’m pretty sure he would have been referred straight up to the hospital for tests,’ she said.

‘And I just find that a disaster still to this day.’

If you, or anyone you know, needs support, contact:

Log in below to join the conversation.

addiction alcohol alcohol dependence AOD cirrhosis GP–patient relationship liver disease mental health

newsGP weekly poll

Health practitioners found guilty of sexual misconduct will soon have the finding permanently recorded on their public register record. Do you support this change?