Feature

Will COVID vaccines need to be updated to beat new variants?

Vaccine makers are gearing up for a new challenge: providing coverage against the multiple variants replacing the original coronavirus strain.

In the race to stay ahead of the evolving virus, experts say vaccine makers will benefit – or be hamstrung – by the original platform they chose for their candidates.

In the race to stay ahead of the evolving virus, experts say vaccine makers will benefit – or be hamstrung – by the original platform they chose for their candidates.

When virologist Dr Kirsty Short first saw SARS-CoV-2 under a microscope last year, she was a little underwhelmed. Was this unassuming cold-like virus the cause of the global upheaval?

But when she introduced the virus to human nasal cells, it was a different story.

‘Oh my gosh, how it spread,’ the University of Queensland researcher told newsGP.

And how it has spread. The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 disease turned the world upside down and has triggered one of the largest scientific endeavours in generations, as thousands of scientists, researchers and clinicians work to understand the new foe.

Vaccines arrived within a year – much faster than the previous record (four years, for a mumps vaccine).

But the virus has not been sitting still. It’s a moving target, shifting before our eyes. New coronavirus variants of concern have evolved into being in recent months, appearing even as countries begin the long process of vaccinating their populations.

The more transmissible B.1.1.7 variant first found in the UK may already be supplanting the original strain. According to Australian Chief Medical Officer Professor Paul Kelly, 80 countries have seen community transmission of B.1.1.7 and it is fast becoming ‘the normal strain of the virus that is circulating around the world’.

For her part, Dr Short is watching two other variants in particular – the B.1.351 that first appeared in South Africa, and the P.1 variant present in Brazil.

Both of these countries were slammed by the original strain, with very high rates of infection in some areas.

This, Dr Short believes, is not a coincidence.

‘The virus is adapting to pre-existing immunity – that’s what drives adaptation,’ she said.

‘Especially in Brazil, I think what happened was a wave of infections very early on, with lots of people developing antibodies. But as soon as you have pre-existing antibodies, that’s selective pressure for the virus.

‘Variants are selected when they have a competitive advantage. I think what we’re seeing is the ability to evade pre-existing antibody response.’

Does this mean that our existing stocks of vaccines are less useful – even before we really start vaccinating in earnest?

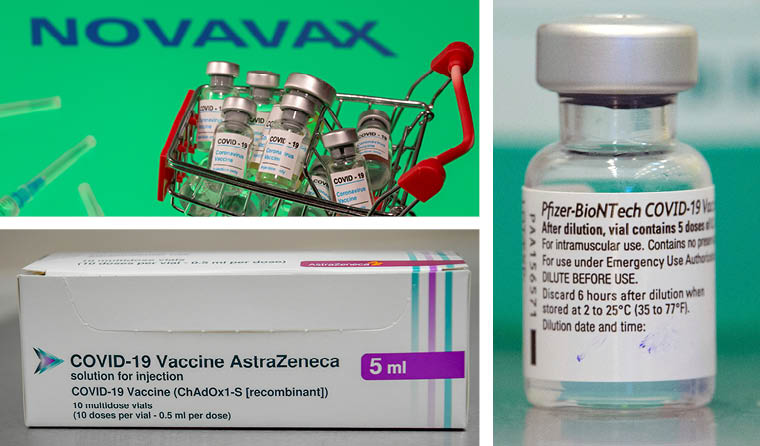

Hardly. Dr Short and other experts point out that even the vaccines made by Novavax and AstraZeneca, now shown to be less effective against the South African variant, should still protect us from severe illness or death.

The emergence of COVID variants has triggered a new race among vaccine manufacturers.

By vaccinating with existing stocks, they say, we reduce the amount of virus circulating in the community – and reduce the chances of the virus evolving to a true escape mutant able to entirely evade antibodies induced by original vaccines.

‘I’m not freaking out about these variants. This is what viruses do,’ Dr Short said.

‘We should continue with our vaccine strategy as is, while perhaps starting to prioritise the vaccines that have been tested against the variants with at least some efficacy. That may be the way forward.’

Kirby Institute virologist Associate Professor Stuart Turville told newsGP that with changes to the virus occurring in real time, it is vital to blunt its advances through immunisation with existing vaccines, while simultaneously monitoring for new changes.

‘These two variants [B.1.351 and P.1] are two we know of. But we don’t know what we don’t know. Are we going to see another in the US? In other areas of the world? We need to be prepared to deal with these changes,’ he said.

‘In the best-case scenario, we could simply plug and play and change the vaccine so it can deal with new variants. But we haven’t tested that yet.

‘Can we change it to be a seasonal vaccine? Can we keep it up-to-date? Or do we potentially do a cocktail of vaccines? All of these questions are being asked to find the solution to give better breadth for our vaccine response.’

Professor Jamie Triccas, who heads the infectious diseases and immunology discipline at the University of Sydney, told newsGP it is now clear that booster shots targeted against the South African-origin B1.351 will be necessary.

‘While the vaccines we signed up for have been shown to be very good [at] reducing severe disease irrespective of the variant, if we want to reduce transmission overall we are going to need vaccines specific to them,’ he said.

‘That may be in the form of giving a first-generation vaccine, with a booster for additional immunity for circulating variants. Many companies have indicated that’s what they are moving towards.

‘This is not at all a concern – it happens with other viruses. We have the tools to do this.’

As Professor Triccas observes, the emergence of the variants has triggered a new race among vaccine manufacturers, with many planning to release booster shots or otherwise update their vaccines.

A new race to beat the variants

In the emerging race to stay ahead of the evolving virus, experts say vaccine makers will benefit – or be hamstrung – by the original platform they chose for their vaccine.

The likeliest early winners will be the new mRNA vaccines developed by Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech. The technology their vaccines rely on will be able to move fastest to accommodate changes to targets on the virus variants, according to Professor Terry Nolan, who heads vaccine and immunisation research at the Doherty Institute.

However, he told newsGP that all platforms should still be able to refocus their vaccines on new variants of concern.

‘There is light at the end of the tunnel but it’s the length of the tunnel and the complexity,’ he said. ‘[Updating vaccines] is readily achievable and new platforms make it much more possible much more quickly.

‘It’s easiest for mRNA vaccines to contain more than one script for a protein; you create the mRNA for that variant [with a] likely focus on mutations in the receptor binding domain, which are the mutations of most concern.

‘For recombinant vaccines like Novavax, you can have two proteins in the vaccine without worrying about interference. For adenovirus vaccines, I’m fairly sure you could do the same and paste a new sequence and specify two different proteins.’

By contrast, traditional inactivated virus vaccines such as China’s Sinopharm may find it harder to change target quickly.

mRNA COVID vaccines like those produced by Pfizer/BioNTech will likely be able to adjust to new variants faster than those produced by Novavax or Oxford University/AstraZeneca.

Overall, the technology is here and ready to achieve the shift, Professor Nolan said, but the task is not trivial.

One potential stumbling block is achieving approvals without having to resort to full-scale clinical trials.

‘There’s a sense that this can be done in a matter of weeks – but it will take much more [time],’ Professor Nolan said.

‘Regulators haven’t yet been tested in terms of what data they will require to approve a change to the target antigen in new versions of existing vaccines.

‘It could possibly be similar to the flu vaccine, where a smaller sample of human subjects might be required to ensure there are no unexpected safety issues and ensure an antibody response in humans. So regulatory approvals will need to be sped up – and simplified.’

More positively, a recent preprint based on AstraZeneca’s UK trials have demonstrated for the first time that a vaccine is likely to actually cut transmission.

In the Lancet preprint, researchers note that after a single dose of the Oxford University/AstraZeneca vaccine, overall PCR positive cases were reduced by 67%, ‘suggesting the potential for a substantial reduction in transmission’.

‘With that protection against asymptomatic cases, it’s not unreasonable to infer protection from transmission,’ Professor Nolan said.

‘If the immune system is stopping you getting any symptoms, it has to be a very good healthy immune response. And if that is the case, it’s very likely you won’t have enough virus to transmit to someone else.’

A Pfizer Australia & New Zealand spokeswoman told newsGP that recent in vitro studies suggest the existing Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine can ‘effectively neutralise’ the coronavirus with a key mutation found in the UK and South African variants.

‘If the virus mutates such that an update to the vaccine is required to continue to confer protection against COVID-19, we believe that the flexibility of BioNTech’s proprietary mRNA vaccine platform is well suited to enable an adjustment to the vaccine,’ she said.

AstraZeneca Australia was approached for comment.

How long would it take to update?

According to University of Sydney vaccine expert Professor Robert Booy, mRNA vaccines should be able to adjust to new variants every 2–3 months from a technical standpoint, though regulatory approval is as yet unknown.

Viral vector vaccines such as Oxford University/AstraZeneca’s candidate, however, could take up to six months.

Both, he told newsGP, are still very impressive, given we only manage to update flu vaccines annually.

‘In the last two months, we’ve seen six effective and safe vaccines tested in humans. That is literally amazing,’ he said.

‘These vaccines are especially protective against severe disease, hospitalisation and death. There are huge reasons for optimism. We just have to adapt the vaccines – the same way the virus adapts its genetics.

‘A year from now, it’s possible we could have vaccines that cover more than one variant, as well as vaccines providing one kind of protection in the first dose with a slightly different booster protection in the second dose.’

Log in below to join the conversation.

coronavirus COVID vaccines variants

newsGP weekly poll

How often do patients ask you about weight-loss medications such as semaglutide or tirzepatide?