News

Claims of gene-edited babies trigger major controversy

Claims by a Chinese scientist to have created the first CRISPR gene-edited babies have been met with a worldwide outcry.

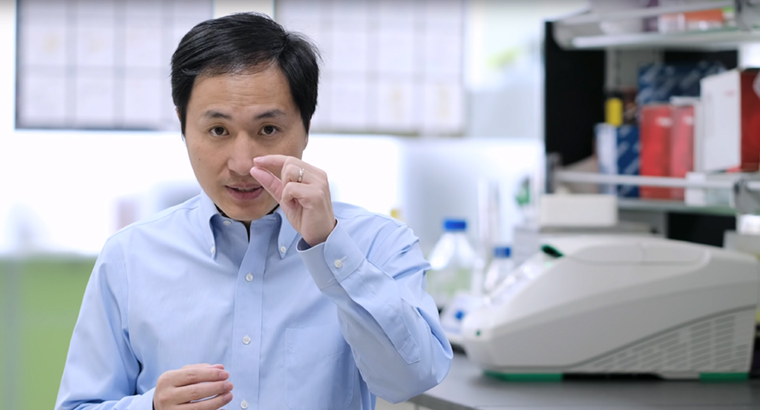

Associate Professor He Jiankui has defended his controversial experiments into genetically edited babies.

Associate Professor He Jiankui has defended his controversial experiments into genetically edited babies.

Two embryos edited as part of a clinical trial using IVF and CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) to eliminate the CCR5 gene have resulted in healthy girls born several weeks ago, according to reports in the Associated Press and Technology Review.

The aim, according to the scientist responsible, Associate Professor He Jiankui, was to make the girls immune to HIV, smallpox and cholera. The girls’ father is HIV-positive. The parents were given free IVF in exchange for permission to do the experimental gene editing.

The claim comes three years after researchers elsewhere in China first edited a human embryo, though it did not lead to a birth.

Following news of the gene-edited births, backlash from the world’s medical community has been swift and highly critical, particularly since there are established effective means of HIV prevention that do not require genetic tweaks.

University of Melbourne Associate Professor and GP Grant Blashki said the backlash is unsurprising.

‘If claims are true that CRISPR gene editing technology has been used on embryos for the purpose of HIV prevention resulting in live births, it is no surprise that there has been loud worldwide disapproval,’ Associate Professor Blashki, who is an RACGP Genetics Advisory Committee member, told newsGP.

‘The consensus is that this endeavour is premature, crosses many ethical lines, including patient safety, has unknown implications for future generations, is not an appropriate approach to preventing HIV, and puts at risk the field of properly approved gene-editing research for severe medical conditions.’

University of Sydney Associate Professor of Bioethics Ainsley Newson said it seemed Professor Jiankui ‘wanted to be first rather than waiting to be safe’.

‘It is still early days for human genome editing, with lots of scientific and ethical issues needing to be ironed out before it is used to change a genome of an embryo and its future descendants,’ Associate Professor Newson said.

‘Susceptibility to HIV infection is not an obvious target for genome editing. We don’t need genome editing to prevent HIV; we need to make existing preventive measures and treatments more widely available.

‘Editing the DNA of healthy embryos to reduce the risk of contracting HIV is neither necessary nor appropriate.’

Reproductive biology expert and South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI) science communicator Dr Hannah Brown said ‘cowboy-style’ researchers risk damaging the fragile relationship between science and society.

‘For each research story of hope, another is published providing evidence of off-target effects, and large deletions incorporated at the cut site, all of which suggest that research needs to proceed cautiously,’ she said.

‘CRISPR-based gene editing is very much still in the experimental stage, particularly in human embryos, where the most recent research questions the success rates and efficacy of the technology.’

Dr Brown said there are major concerns with the way the trial was run, such as conflicts of interest of researchers who had a financial stake in the success of the technology, and the fact an embryo with a known failure in the editing process was transferred regardless.

‘[That suggests] they were actually interested in testing the safety and efficacy of the technology and not the genetic resistance to HIV for the patients and babies,’ she said.

Professor Jiankui defended his experiments in a series of YouTube videos.

‘The media hyped panic about Louise Brown’s birth as the first IVF baby. But for 40 years, regulations and morals have developed together with IVF, ensuring only therapeutic applications to help more than eight million children come into this world,’ he said.

‘Gene surgery is another IVF advancement and is only meant to help a small number of families. For a few children, early gene surgery may be the only way to heal an inheritable disease and prevent a lifetime of suffering. Their parents don’t want a designer baby, just a child who won’t suffer from a disease which medicine can now prevent.

‘Gene surgery is and should remain a technology for healing. Enhancing IQ or selecting hair or eye colour isn’t what a loving parent does. That should be banned.

‘I understand my work will be controversial. But I believe families need this technology and I’m willing to take the criticism for them.’

In a separate video, Professor Jiankui defended the choice to eliminate the CCR5 gene. He said CCR5 is one of the best-studied genes, with more than 100 million people worldwide possessing a genetic variation disabling the gene and offering protection against HIV.

‘Why CCR5? First, safety. Second, real-world medical value,’ he said.

CRISPR gene editing genetics genomics

newsGP weekly poll

Sixty-day prescriptions have reportedly had a slower uptake than anticipated. What do you think is causing this?