Feature

‘Be a man, toughen up’: Masculinity and mental health in the AFL

When former footballer Wayne Schwass heard AFL star Majak Daw had been seriously injured after a fall from a Melbourne bridge, he was deeply shaken.

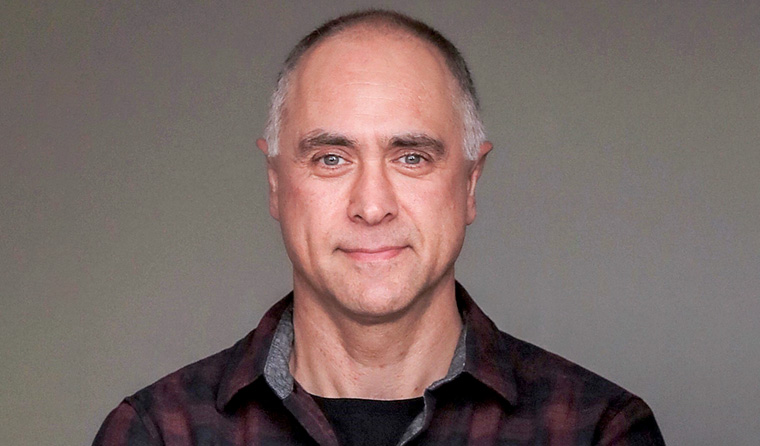

‘My greatest concern is that we won’t see change until something devastating happens.’ Wayne Schwass on his concerns for athletes’ mental health.

‘My greatest concern is that we won’t see change until something devastating happens.’ Wayne Schwass on his concerns for athletes’ mental health.

It wasn’t just that Mr Daw played for his former club, North Melbourne. For Mr Schwass, it was further evidence the AFL still has a great deal of work to do on the issue of mental health, more than 15 years after he first started his own lobbying efforts.

The CEO of mental health social enterprise Puka Up called for immediate action on mental health:

More than a month after the incident, as Mr Daw

continues to recover, Mr Schwass told

newsGP that the need for practical – and cultural – change remains urgent.

He said football clubs spend a majority of their budget on their players’ physical preparation, performance and rehabilitation – and almost nothing on their mental health.

‘I’ve been lobbying my industry for 15 years. It’s one of my great frustrations that any AFL club will have 10 or 20 people in the sports condition team, with doctors, running coaches and so on, but we have clubs at the elite level who don’t have a single part-time psychologist,’ he said.

Mr Schwass believes clubs’ heavy focus on the physical component of their athletes comes at the expense of the mental element.

‘[It’s about], how can we get them stronger, bigger, fitter, faster, more consistent athletes who recover or are rehabilitated and back on the field as fast as you can?’ he said.

‘But we’re missing an opportunity to identify and prevent psychological issues much earlier, which means the outcomes would be better.’

Since retiring from the AFL in 2002, Mr Schwass has worked to change the culture at AFL clubs and management on mental health.

He suffered from serious depression during his own successful AFL career. In 2017, he posted an image of himself celebrating winning the 1996 premiership. He captioned the image: ‘This is what suicidal looks like.’

Mr Schwass said what is needed as a well-designed framework involving players, coaches, clubs and stakeholders, working collaboratively on the issue.

‘We need to develop a culture that encourages and supports everyone when we’re dealing with mental health conditions. And we need to do that yesterday,’ he said.

‘While there’s a broad level of acceptance that this is serious, we as an industry don’t know what to do.

‘It would be my strong recommendation that we start to invest some of the conditioning money to getting properly trained psychologists or psychiatrists in – and not sports psychologists, because that’s related to performance.

‘For every AFL player we know of with mental health conditions, we can assume a significantly higher number who are living with similar things but who don’t speak of them to anyone. We need to change that culture and environment.’

A key issue, Mr Schwass said, is the fact elite sportspeople are in the public eye.

‘The AFL has more accredited media personnel than players. It’s an industry within an industry, critiquing, opinionated, pulling apart performances on and off the field,’ he said.

‘There are unique characteristics that are additional stresses that can exacerbate issues. There’s the public profile, the nature of the role they play.

‘Yes, players get paid a ridiculous amount of money relative to the rest, but the wider community doesn’t see the expectations, the pressure to perform at a high-level consistently.

‘There’s self-doubt, injuries, gambling issues, relationship issues, the negative role social media plays. It’s hard to comprehend the enormous pressure these young men are under.

‘We expect them to be modern-day gladiators who play well over time. But the player who just had a bad game – his parents might have separated, or his dad might have got cancer or his relationship just ended.

‘We train them to cope with stress in one area – the sporting field. But we don’t train them to be emotionally expressive so they can cope with feeling upset or overwhelmed. We don’t equip them with the emotional tools they need.’

Mr Schwass believes the problem is entwined with how young men are socialised.

‘This notion of [stoic] masculinity is problematic. Boys and girls are born emotionally connected and expressive. They’ll cry, laugh and go to their parents for comfort at an early age,’ he said.

‘But, for men in particular, there’s a tremendous amount of gender conditioning applied: “Be a man, toughen up, don’t cry”. We narrow the emotional skill set of young boys. It’s fundamentally flawed.

‘Of the eight suicides we have in Australia a day,

six are men.

Mr Schwass said it is possible to achieve a similar groundswell to the AFL’s progress on racial vilification, where there has been a significant shift in community expectations and standards.

‘My greatest concern is that we won’t see change until something devastating happens. My greatest fear – and I hope I’m horribly wrong – is that we’ll lose a player to suicide,’ he said.

‘It doesn’t have to get to that situation. Our game has a wonderful opportunity to change, and change community expectations and attitudes too. I believe in the value and necessity of doing this.’

masculinity mens health mental health sports medicine

newsGP weekly poll

As a GP, do you use any resources or visit a healthcare professional to support your own mental health and wellbeing?