Column

From mutineer to surgeon: The curious case of William Redfern

Dr Gillian Riley tells the story of the first colonial doctor to be qualified in Australia.

William Redfern became one of the most popular private doctors in the colony of New South Wales. (Image: SLNSW)

William Redfern became one of the most popular private doctors in the colony of New South Wales. (Image: SLNSW)

In 1797, a 19-year-old British junior naval medical officer wrote a letter to his shipmates in the midst of their mutiny at the Nore anchorage in the Thames Estuary.

In his letter, the young man advised them to be ‘more united amongst themselves’.

It was for that reason, when the mutiny was finally broken, that he was tried as one of the leaders.

Penalties for mutineers were harsh, and for ringleaders especially brutal. Most of the leaders of the Nore mutiny were hanged. Our 19-year-old was spared – not because he had only written a letter, but because of his age.

After four years in the less-than-salubrious British prison system, he requested and was granted transportation to the new colony of New South Wales.

That 19-year-old’s name was William Redfern. It might be familiar because they named a suburb after him on the other side of the world.

Surgeon’s mate

Mr Redfern helped the assigned surgeon on board the convict ship travelling to Australia and, by the end of the voyage, had slid back into the position of surgeon’s mate he vacated four years earlier.

After arriving at the new colony, Mr Redfern was transferred to Norfolk Island, where he acted as assistant surgeon, despite still being a convict. He performed his duties ably, earning a conditional and eventually a full pardon in 1803.

Once he’d earnt his pardon, Mr Redfern went to Sydney and began to work at the colony’s primary hospital at Dawes Point. It was a ramshackle place that began as a set of tents which gradually gave way to buildings. The hospital had always been poorly equipped and of an inadequate size. A new hospital was eventually built on Macquarie Street, but this did not seem to solve the issues. The fact convicts provided much of the nursing care meant it could be somewhat rough. Stealing was rife and it remained hard to find equipment – and beds.

Mr Redfern still had no formal qualifications (being sentenced to death will have that effect on your career), but was soon appointed regardless. The reason, in the words of the Lieutenant–Governor of the Colony, was due to ‘the distress’d State of the Colony for medical aid.’

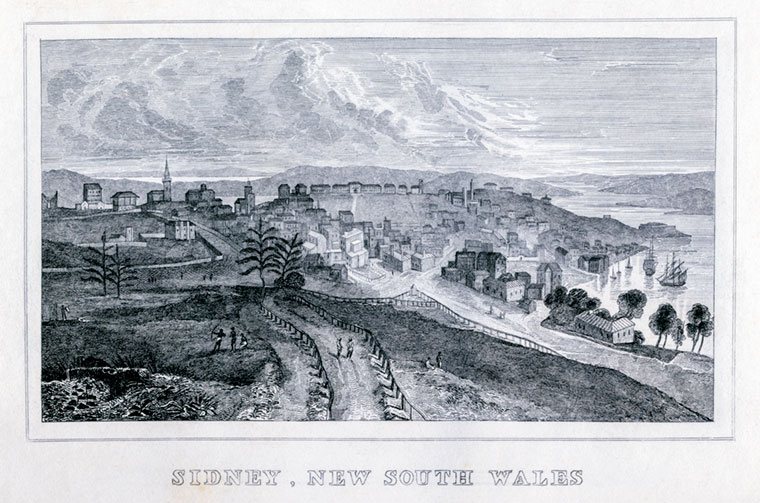

Early 19th century Sydney, where Mr Redferan began work at the colony’s primary hospital in Dawes Point.

The others working at Dawes Point examined Mr Redfern in medicine and surgery. Finding his skills to be excellent, they awarded him his qualifications. This was to set a precedent for many years as to how doctors would attain qualifications in the colony of NSW, long before the advent of medical schools, colleges and endless examinations.

(On a personal note, I wish I could have just convinced a couple of my mates to say, ‘Hey, she’s a good doctor’, because I reckon that would have been a lot less stressful than the KFP.)

Mr Redfern continued to work in the hospital, where he taught the first Australian medical students, but also set up an extensive private practice in Sydney. He became one of the most popular private doctors in the colony and was the private doctor for the families of the influential NSW Governor Lachlan Macquarie and Lieutenant John MacArthur. In fact, Mr Redfern saved the life of MacArthur’s daughter and delivered Macquarie’s son. After that, both were willing to do just about anything to advocate for his career.

Close to his roots

Mr Redfern did not forget where he started. He conducted daily outpatient clinics for convicts from Dawes point and then Sydney Hospital, and advocated on their behalf to Governor Macquarie for better sanitation and living conditions.

His advocacy resulted in a landmark report that led to the end of many practises causing a great deal of suffering for convicts. Mr Redfern also advocated for widespread introduction of the smallpox vaccination. Over time, he became an avid emancipationist, advocating for the rights of former convicts in the colony.

Mr Redfern married in 1811, and he and his wife had two sons. His family moved to a 100-acre area of land in Sydney’s east (which is now the site of his eponymous suburb). He would add to these landholdings throughout his time in NSW.

While he had the support of Governor Macquarie, Mr Redfern’s history was not forgotten, nor was his brusque demeanor. When the principal surgeon of Sydney Hospital retired in 1818, Mr Redfern was overlooked for the role, and he promptly resigned from the Colonial Medical Service.

Macquarie, most likely in an attempt to mollify him, soon appointed Mr Redfern as a magistrate, only for Governor Bathurst to remove him the following year.

Despite these blows, Mr Redfern remained the most popular and trusted private doctor in the colony until he gave up his practice in 1826. Two years later, he returned to England for his son William’s education. Despite his stated intention to return to Australia, Mr Redfern never did so, and died in England in 1833.

While he may have been frustrated at his inability to progress in later life, I wonder if Mr Redfern would have felt differently if he knew history would record him as the first doctor to receive an Australian qualification and the first to educate an Australian medical student.

I have always had a theory that GPs have a bit of a rebellious streak to us as a specialty. Maybe, just maybe, it’s because the first Australian qualified generalist was a mutineer and a convict with a pronounced spirit of independence.

medical history William Redfern

newsGP weekly poll

Health practitioners found guilty of sexual misconduct will soon have the finding permanently recorded on their public register record. Do you support this change?