Column

Old doc, new data: Ezetimibe

Dr Casey Parker weighs up the pros and cons of new data on a medication for high cholesterol.

How useful is ezetimibe for patients?

How useful is ezetimibe for patients?

For the majority of my career, only one class of drugs has been used to treat hypercholesterolemia: the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, aka the statins.

However, I have recently started seeing dyslipidemic patients returning from their consultations with cardiologists, who have been started on a newer medication: ezetimibe.

The name itself is quite hard to fathom. Could it be an obscure Japanese radish? The use of a ‘z’ and multiple potential accent points make it a tricky one to pronounce.

But rather than spending too much time of tangling with its label, I thought I would dive into this newer drug’s pharmacology and efficacy in an attempt to become better acquainted.

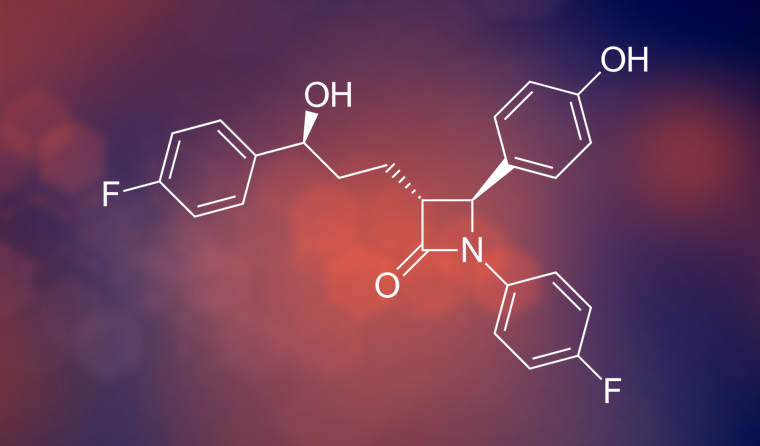

Ezetimibe works by blocking the absorption of cholesterol in the small intestine and liver. It acts on a very specific protein – the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 protein – on the gastrointestinal tract epithelial cells. I bet you didn’t learn about that in physiology class.

Fun fact: it is also thought that the hepatitis C virus uses the exact same protein to invade liver cells. So there is some emerging research into the use of this agent in treating hepatitis C.

As you might expect from its mechanism, ezetimibe’s common side effects include malabsorption symptoms such as abdominal cramps, diarrhoea and flatulence.

Given the fact it blocks cholesterol absorption, one might anticipate problems with vitamin D absorption, too. However, there is not much data to support a link to any clinically significant vitamin D deficits in practice. I guess you could check for it, but that is a whole other can of helminths.

Annoyingly, ezetimibe can also produce myalgias and joint pains. Given it is usually co-prescribed with a statin, this will make it tricky for you to work out which drug needs to be stopped to solve the pains.

Interestingly, there is a theoretical interaction with warfarin as vitamin K is also transported by this mechanism. In a great example of a bug becoming a feature, it seems that ezetimibe may actually stabilise INR levels, at a slightly lower level, in patients taking warfarin.

The best evidence suggests that ezetimibe does reduce your patient’s cholesterol – but only really by a nudge. Most of the trials show a reduction of 10–20% in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels. This is a laboratory-oriented outcome, or a LOO. Sure, the drug may move the test results into a happier bracket, but we prefer to see patient-oriented outcomes (the unfortunately named POOs).

So, has it actually been tested with regards to POOs? There is only one clinical trial. The IMPROVE-IT trial was big – 18,000 patients who were randomised immediately after a myocardial infarction to receive simvastatin 40 mg plus either ezetimibe or placebo. They were then followed for an average of seven years. Nearly half of the patients dropped out of the trial, which limits its external validity.

It is important to note, however, that this is not the maximal dose of simvastatin. It could be argued that these high-risk patients may get more benefit by just adding a bit more statin, rather than a medium-dose statin plus ezetimibe. Maybe a better trial would combine maximal tolerable statin plus ezetimibe to be more pragmatic.

In the end, the trial found a small reduction (2%) in some components of the composite primary outcome. This was due to a reduction in non-fatal strokes and myocardial infarctions, but there was no mortality benefit.

To summarise, ezetimibe showed a small benefit in a very high-risk, secondary prevention cohort with an especially long follow up. Composite outcomes lend themselves to statistical cherry picking. In the end, no lives were saved.

In this trial – sponsored by the drug company – there was no difference in significant side effects. I am often wary about trial-reported side effects, since we often find out a lot more in post-marketing data.

But, taken at face value, ezetimibe seems like a pretty benign intervention. Small benefits, but small risks.

This arguably makes it worthwhile in the high-risk patients. For my part, though, I am reluctant to change practice on the back of a single, pharma-funded trial.

Most importantly, we need to be aware that the market for primary prevention is huge and ezetimibe has never been proven useful in this population. This is a great example of spectrum bias being used to amplify the effect size of a medication that may lead to indication creep.

How do I think we should prescribe ezetimibe? For now, I do not believe we should use it in primary prevention. There is simply not enough data.

In secondary prevention, we need to look at the absolute risk. We know that optimising lipid levels can translate to improved POOs. Statins are known to work, with proven mortality benefits.

So if we can get good lab results with a statin, then that will probably suffice. Of course, we should try to modify all of the other components of our patients’ cardiovascular risk before reaching for yet another pill.

Ezetimibe possibly fits where we either cannot move the lipids with decent statin doses or where the statins are not tolerated. This is probably a small number of higher risk, post-event patients.

My bottom line? Small gains – for a small number of patients.

cholesterol ezetimibe medication statins

newsGP weekly poll

Would it affect your prescribing if proven obesity management medications were added to the PBS?