News

ACCHOs face challenges of vaccine rollout to remote communities

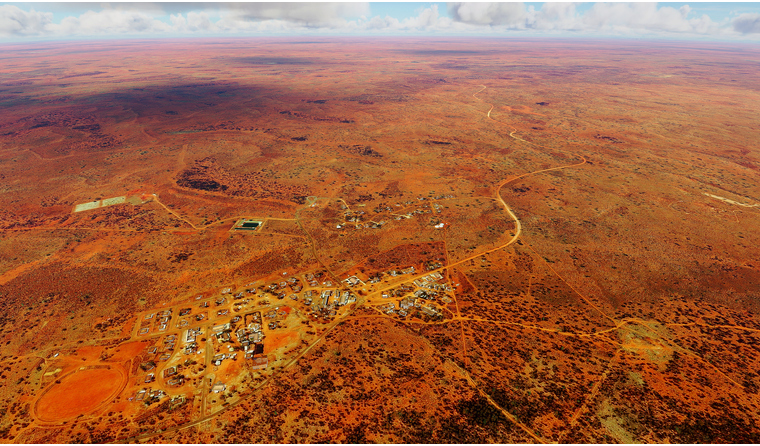

As Australia’s COVID vaccination campaign inches closer, Aboriginal health services prepare for a mammoth effort.

Environmental factors are among the logistical challenges that need to be considered for vaccine delivery to remote communities, says Darwin-based GP Dr Andrew Webster.

Environmental factors are among the logistical challenges that need to be considered for vaccine delivery to remote communities, says Darwin-based GP Dr Andrew Webster.

Since COVID-19 arrived on Australia’s shores, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs), alongside communities and local organisations, have successfully managed to keep the virus from spreading to remote and vulnerable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

But as Australia moves closer to rolling out its COVID vaccination campaign, they now face a new set of logistical challenges.

Darwin-based GP Dr Andrew Webster, Head of Clinical Governance with the Danila Dilba Health Service, told newsGP Mother Nature is a key factor to consider.

Currently wet season, he says significant rainfall has resulted in a number of road closures, making some remote communities inaccessible.

‘It’s not particularly unusual, so it’s something we’re aware of. But it will mean that getting vaccines out to communities or places that need to receive vaccinations is going to require some additional planning,’ Dr Webster said.

‘We [also] often see more power outages at this time of the year because lightning strikes or wind knocks down trees, and so there is more risk of vaccine loss or vaccine wastage because fridges turn off. That’s something that needs to be factored in.’

The Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is the only candidate that has been approved for use by the Therapeutic Goods Administration so far, and is set to be first off the rank under phase 1a of the roadmap.

The Federal Government announced on Thursday it had secured an additional 10 million doses of the vaccine, which has an efficacy rate of 95%, the highest of the three candidates secured by Australia.

However, Department of Health Secretary Professor Brendan Murphy says it is more likely those in remote communities will receive the Oxford University/AstraZeneca candidate due to Pfizer/BioNTech’s cold chain storage requirements.

‘We’ve got a very specific plan working with the Aboriginal controlled sector, but it’s likely that we won’t be prioritising the use of a difficult logistic vaccine for that population,’ he said.

But Western Australian Greens Senator, Rachel Siewert says that is not good enough.

‘Since when has it been beyond the wit of Australia to be able to get important supplies out to Aboriginal communities?’ she said.

‘We know our First Nations communities are some of the most vulnerable communities. We should be committing to rolling out our Pfizer vaccines to vulnerable First Nations communities, because we can do it.’

Dr Jason Agostino, Medical Advisor at National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) and member of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID-19, told newsGP the organisation’s current efforts are focused on the logistics of rolling out the Oxford University/AstraZeneca candidate.

However, he added that the Government is yet to officially rule out use of Pfizer/BioNTech’s candidate for particularly vulnerable cohorts.

‘It’s obviously more challenging. [But] it’s not to say that you can’t possibly do outreach from Pfizer hubs into remote communities; they have a five-day storage life outside of the -70°C environment,’ he said.

‘So it still does remain a possibility that you could take it from the Pfizer hub into a remote community.’

None of the COVID vaccine candidates have been approved for use in people under 18, meaning up to 20% of people in some communities may not be protected.

As it stands, for a COVID vaccine to be administered in general practice or ACCHO settings, a doctor is required to be present, which Dr Webster says is often ‘not very practical’ for very remote communities.

But Dr Agostino says the Government has made it clear that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioners will be able to administer the vaccine under their state or territories’ existing legislation, but will not be eligible to claim the Medicare Benefits Scheme unless a doctor is present.

‘That increases the amount of people that can vaccinate and decreases the reliance on having to wait for a GP to come out, which can often be quite infrequent,’ he said.

‘We’re now just waiting for information from our … Aboriginal community controlled health services.

‘They’ve gone through a separate process to become a vaccine provider than the EOI that went out for GPs. We’re going to be looking at that and seeing where they think they have capacity issues, and how we can then support them to become a vax centre.’

Unlike the cap for 1000 general practices, all 143 ACCHOs can become vaccine providers if they are willing and meet the requirements.

Based on current guidance, COVID vaccines will only be administered to people aged 18 and over. For some remote communities that will mean at least 20% of the population or more will not be protected against the virus.

In 2020, a higher proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people compared to non-Indigenous people received the flu vaccine.

The Danila Dilba Health Service achieved close to 60% coverage, its highest uptake on record. But Dr Webster says their efforts will no doubt have to be ramped up.

‘I don’t think there’s enough data yet from overseas studies about how herd immunity works and how effective the vaccines are at preventing infection and spreads,’ he said.

‘What that’s going to mean is that we could try and set ourselves a target of 70%, for example. But we’ll absolutely be trying to get that higher than that and get as close as possible to 100% of the eligible population vaccinated.’

Despite the introduction of the national booking system, Dr Webster says it is likely people in remote communities will book their vaccination directly through the local health service.

Meanwhile, Dr Agostino says recalling people for their second dose of the vaccine is likely to pose a challenge.

‘We know it’s going to take a lot of our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workforce [and] a lot of our transport staff to get those people in for that second dose,’ he said.

‘Doing a recall isn’t as simple as sending someone a text. People have problems with transport [and] people have problems with connectivity in remote areas.’

But to ensure uptake, Dr Agostino says efforts now must be focused on addressing any vaccine hesitancy through education around vaccine efficacy and safety.

‘And making sure that we’re communicating through the appropriate channels, and then sometimes in the appropriate language for remote Aboriginal communities,’ he said.

‘There are a whole bunch of challenges, but these services are used to doing hard things for the benefit of their communities.’

Log in below to join the conversation.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander coronavirus COVID-19 logistics vaccine rollout

newsGP weekly poll

Health practitioners found guilty of sexual misconduct will soon have the finding permanently recorded on their public register record. Do you support this change?