News

Students say no to more Australian medical schools

Greater numbers of medical schools will increase pressure on existing students and will not tackle the real cause of the rural doctor shortage, the President of the Australian Medical Students’ Association told newsGP.

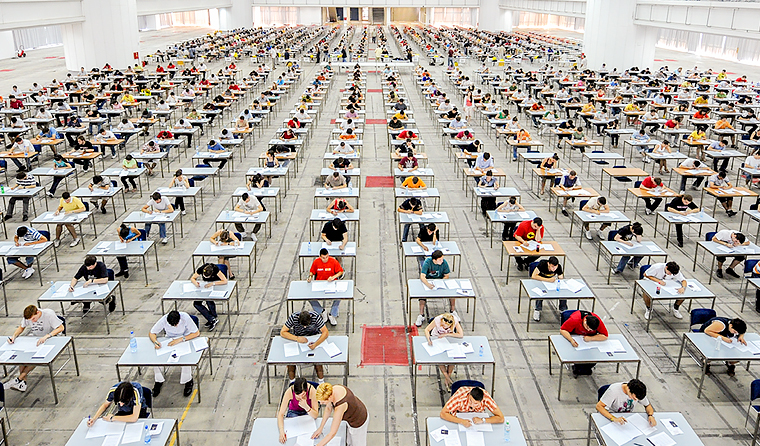

Increasing competition may bring further stress and pressure for medical students.

Increasing competition may bring further stress and pressure for medical students.

Early mornings on rotation, late nights crouched over textbooks, lectures, research projects and hours on your feet, desperately hoping you won’t make an exhaustion-clouded mistake – welcome to the life of a medical student.

But add to this a proliferation of medical schools and an explosion in students competing for internships, and the stresses of the medical training process can be sharpened to a knife’s edge.

‘We are graduating all of these junior doctors, but there aren’t enough specialist training positions to turn them into fully qualified, independent doctors who can practise within our communities,’ Australian Medical Students’ Association (AMSA) President Alex Farrell told newsGP.

‘By 2030 it’s projected that 1000 junior doctors will miss out on vocational training every year. You really feel that pressure at a medical student level.

‘I know students who haven’t had a holiday since they first started medicine, because in their free time they are cramming research projects, doing additional study – anything to give them an edge to get onto a training program they’ll be applying for in five-plus years.’

That type of pressure has taken a toll on the mental health of some medical students.

‘When there’s growing job insecurity for students and fears of what’s to come, that is very likely to have mental health repercussions,’ Ms Farrell said.

‘Medical students and junior doctors are worked hard. To go through all the stress and pressures of studying medicine and then not be able to progress in that is a really devastating prospect.’

Chinthuran Thilagarajan, a final-year medical student at the University of Sydney, has certainly felt the influence of increased competition.

‘I think it’s a big impact on my life and how I study,’ he told newsGP. ‘[Medical students] want to focus on our education and figure out the fundamentals we’ll need when we’re out there in workforce.

‘But with more and more medical schools popping up, and therefore more students, the challenge of studying is more stressful and difficult, because it’s always on your mind: do you need to start gearing your life towards competition now? Should you be working on a research project in your down-time?’

In this context, it is hard for existing students to understand decisions to open new medical schools, such as that proposed for the regional NSW town of Orange as part of a new Murray-Darling medical school network. While the school’s supporters claim it will be central to addressing the maldistribution of doctors in rural and regional Australia, Ms Farrell argues this ‘solution’ is focused on the wrong end of the problem.

‘Internships in the Murray-Darling area are already over-subscribed,’ she said. ‘There were eight times the number of applications for the available internship spots in Orange this year. So the junior doctor level is not where the problem exists – it’s further down the pipeline.

‘The current system does allow for medical students to study in these areas, and it also allows internships in these areas. But it becomes much harder to stay in the bush beyond that point because the vast majority of vocational training spots are based in metropolitan areas.

‘So even if a junior doctor has come from a rural background, spent time in rural areas as a medical student and secured a rural internship, they still have to return to the city in order to specialise. And that’s when we’re losing them.’

Ms Farrell understands that producing more medical students seems like an ‘easy fix’ to a rural doctor shortage, but believes the issue would be better served by a different approach.

‘AMSA would love to see a national rural generalist pathway so there is an established program for training rural generalists in the country for those formative years,’ she said. ‘That would not only keep junior doctors in rural areas, but train them to fit the specific needs of the rural community.

‘We also think it’s important that a national medical workforce strategy is established. The medical workforce issue is complex with a huge number of stakeholders, which is why we need to get them all around the table and have a strategy that allows us to look at the real solutions rather than focusing on short-sighted strategies like medical schools.’

Mr Thilagarajan agrees, and hopes for positive changes to the training system in the future.

‘I hope, not for anything outrageous, just that medical graduates are able to get into the specialty they’re passionate about,’ he said. ‘Right now the system is set up to fail them, it’s leading them towards an inevitable bottleneck, and that’s really unfortunate.

‘Increasing the number of medical students isn’t really a sustainable option, we need more avenues for training pathways. We need to be looking at the end of that pathway rather than just funnelling more into the start.’

AMSA medical-students medical-training rural-generalist-pathway rural-health

newsGP weekly poll

Health practitioners found guilty of sexual misconduct will soon have the finding permanently recorded on their public register record. Do you support this change?