Interview

Before Melissa Kang was Dolly Doctor, she was a GP

For a generation of teenage girls, Dolly Doctor answered anxious questions about bodies, puberty and sexual health.

Associate Professor Melissa Kang is passionate about young people and sexual health.

Associate Professor Melissa Kang is passionate about young people and sexual health.

newsGP spoke to Associate Professor Kang about sexual health, general practice, and what changed over 23 years and thousands of handwritten letters she received before Dolly moved online in 2016.

How did you become interested in sexual health?

Sex education was woefully absent in my life, as for many in my generation. My parents found it really difficult, as did many of my peers’ parents.

My father was Chinese and my mother was Anglo-Australian, but they both had quite conservative attitudes, particularly towards female sexuality. So I felt this enormous inequity, because I had brothers who were not sanctioned. I felt treated differently. It was subtle, but it was something I observed.

As a young feminist, I was outraged. I was just as smart as my brothers, just as successful, but I was told I couldn’t dress or behave like this. All these things you’re not supposed to do because you’re a woman. That was the start.

Later, when I was studying medicine, I saw young people couldn’t communicate very well with health professionals [about sexual health issues].

How did you become Dolly Doctor?

I was working as a general practice registrar at a new youth health service. The GP there was writing for Dolly at the time, and sometimes we discussed questions. After six months or so, she said, ‘I don’t want to do this any more. Would you be interested?’

Did you feel like a doctor, or an agony aunt?

A doctor – very much.

But I benefitted enormously in the way I approached responses because I worked in a multidisciplinary team, where I was the only GP on team with a bunch of different counsellors. At our lunchtime conversations, we’d intermittently discuss questions – I’d ask them what they thought should go into the answer. It rounded my answers.

So my answers were never just about medical response, but were about understanding adolescent development, or speaking to emotional or psychological stress.

What commonalities were there in the anonymous questions?

From not only answering questions, but then doing content analyses [for academic papers], reading through thousands, you were able to see recurring words and themes.

A big recurring theme was about normalcy. A lot of questions were about, ‘Is my bodily, physical or emotional development normal? Are my feelings normal?’ Some were around sexual arousal, crushes, romantic feelings.

But the great majority were around the physical changes of puberty and whether they were normal or not. Offering reassurance was important.

Dolly Doctor received thousands of handwritten letters from teenage girls asking questions.

What is the role for medical advice columns in the internet age?

Good question. I think young people and adolescents will find places they trust – and will go to. But I don’t know for sure.

I’m guessing it’s not the same. You don’t develop the same relationships as in the past, when there were one or two magazines you’d go to for that anonymous advice. What’s come out of the woodwork since Dolly closed [as a print magazine] is an outpouring of nostalgia from slightly older women saying how much they relied on Dolly and Girlfriend for advice.

This generation has never heard of Dolly Doctor. If I walk into a room of Year 10s, as I did recently, and the adults introduce me as Dolly Doctor, they don’t know what I’m talking about. This generation is yet to discover what relationships they will develop with agony aunts, professionals, mentors, people who guide them.

I don’t know what’s filling that void. Information is out there [online], and most young people are e-literate enough to know what’s credible. But it can still be confusing. Different websites might give conflicting information.

What trends did you observe?

The most significant increase in the type of question was around pubic hair. That was unheard of for the first 10 years, and then crept up and up. How do you remove it? How do you deal with a rash or infection after removal?

Also, I started getting questions about asymmetrical labia, which you’d only notice because there’s no more pubic hair. That’s definitely an influence of pornography becoming available online and being ubiquitous.

So online porn, which doesn’t feature pubic hair at all, would have girls removing their hair, noticing their labia more, and noticing they look different to porn models. That was the most obvious trend.

In a great majority of cases, there was no disclosure of having viewed porn. But I’m absolutely certain these questions were related to viewing porn – them, or a boyfriend or friend.

What remained of concern were the questions girls had around their physical attractiveness to boys, their role in giving boys pleasure, and having to negotiate sex. I saw this trend of what I would call increasingly empowered girls, who were more confident asking about sex. But, at the same time, nothing much had changed. They still often felt pressured or beholden to what boys might want.

Now, that can be hard to tell from a question. But my sense was that a double standard still exists, in that boys felt completely entitled to pleasure and calling the shots, whereas girls have to be confident, empowered, proficient, but had to play second fiddle.

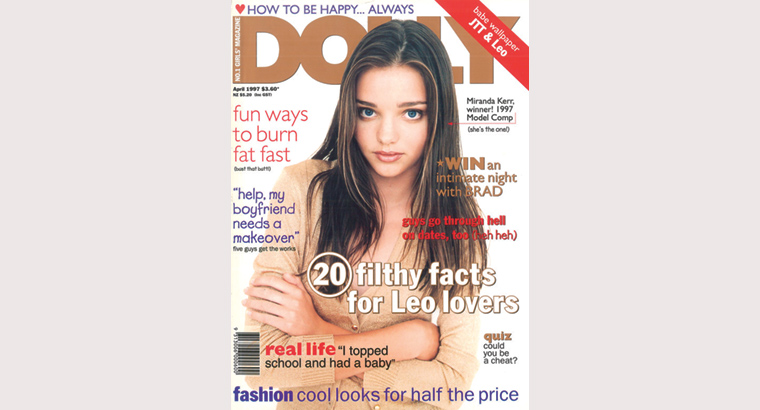

Dolly magazine shifted online after more than four decades of providing advice and reassurance to teenage girls across Australia. (Image: Dolly)

What do GPs do well in sexual health and what could they be doing better?

GPs are increasingly confident in discussing STI [sexually transmissible infection] testing. There’s evidence of that, because we’re seeing more testing being done. And they’ve always been good at discussing women’s health and reproduction.

My sense from talking to registrars each year is that there’s increasing confidence in discussing sex with adolescents. Where could GPs improve? Saying, ‘Would you like to have a chlamydia test?’ – that’s fine, that’s important.

But engaging in conversations around relationships, consensual sex, pleasure, niggling concerns means getting comfortable. Asking about same sex attraction or relationships – there’s definitely more understanding and confidence in talking to patients about sexual diversity, but it’s highly variable.

For some GPs, it’s more difficult to discuss sex and sexuality than others. So it’s about upskilling.

Some of our research has looked at young people with refugee or migrant backgrounds and their experiences with GPs and sexual and reproductive health. If it’s taboo in a young person’s culture, there can be a double whammy when they go to the GP who gives them a lecture.

There’s still a lot to do to make sure GPs are there for all patients. A GP’s cultural background needs to be acknowledged – we are not a-cultural – so we need to understand where we are coming from. When we’re talking to a patient from a different background, it’s about not trying to unconsciously impose our values.

I imagine for many teenagers, the sheer anxiety of asking another human about sex stops a lot of questions being asked. How can GPs best ask about sensitive issues?

What I’ve tried to incorporate when training general practice registrars every year is that when it comes to sex and sexuality, the onus should be on the GP to bring the topic up. That’s especially for young people.

This could be a particularly Australian thing, I don’t know what it’s like in other societies where sex education is very well taught. But in Australia, our young people want GPs to bring the topic up.

Offering chlamydia tests or talking about periods – GPs are usually comfortable with those. But there are those excruciatingly self-conscious questions adolescents have. I don’t think asking about, say, masturbation should be routine. But I think in a more general way, we can say this to young adolescents or older teenagers:

Have you got any concerns around puberty and your physical development? Some of the common things I know adolescents worry about are growth, changing in shape, breast development, pubic hair, genital development.

It’s okay to put those topics out there. The young person might shake their head, go red, say, ‘no, no’. But it does mean when they come back, they know it’s okay to talk about.

So it’s about making oneself approachable and making the topic approachable. You can say these are common concerns and reassure them on confidentiality.

When I do training with general practice registrars, doing role plays is the best way, just practising asking the questions about sex, or doing the confidentiality spiel, so they flow not too awkwardly.

You’ve got to practise doing it until you’re comfortable.

adolescence communication sexual health

newsGP weekly poll

As a GP, do you use any resources or visit a healthcare professional to support your own mental health and wellbeing?