News

Blood clots up to 10 times more common with COVID than vaccines: Study

Research has identified the various risks of people experiencing cerebral venous thrombosis, which has been linked to the AstraZeneca vaccine.

People who contract COVID-19 are 100 times more likely to experience cerebral venous thrombosis than the general population.

People who contract COVID-19 are 100 times more likely to experience cerebral venous thrombosis than the general population.

People who contract COVID-19 are also 100 times more likely to experience cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) than the general population, a new pre-print Oxford University study has found.

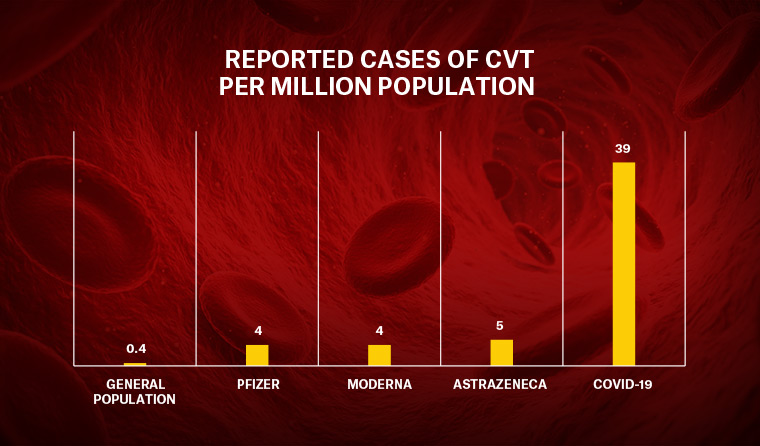

The research, conducted in the wake of numerous high-profile clotting cases linked to people who had received the AstraZeneca vaccine, found around 39 in one million people with COVID are diagnosed with CVT, compared with 0.4 per million people who had not contracted the disease.

CVT was also found to be more common among people who received either the Pfizer, Moderna or AstraZeneca COVID vaccines – at a rate of between 4–5 per million – meaning people with coronavirus are between 8–10 times more likely to develop the blood clots than those who have been vaccinated against it.

‘There are concerns about possible associations between vaccines and CVT, causing governments and regulators to restrict the use of certain vaccines. Yet, one key question remained unknown: “What is the risk of CVT following a diagnosis of COVID-19?”,’ co-lead author Professor Paul Harrison said.

‘We’ve reached two important conclusions. Firstly, COVID-19 markedly increases the risk of CVT, adding to the list of blood clotting problems this infection causes.

‘Secondly, the COVID-19 risk is higher than seen with the current vaccines, even for those under 30; something that should be taken into account when considering the balances between risks and benefits for vaccination.’

To produce their results, the study authors, led by Professor Harrison and Dr Maxime Taquet, counted the number of CVT cases diagnosed in the two weeks following diagnosis of COVID-19, or after the first dose of a vaccine. They compared these to calculated incidences of CVT following influenza, as well as the background level in the general population.

The researchers performed similar comparisons for portal vein thrombosis (PVT), and found it occurred at a rate of 45 cases per million people following vaccination, and 436 per million in COVID-19 infection.

Dr Michelle Ananda-Rajah, a consultant physician in general medicine and infectious diseases at Monash University, said the study ‘clearly shows’ the risk of CVT following COVID-19 infection is higher than either the mRNA or AstraZeneca vaccines.

However, she also said a ‘concern’ with the study is that it conflates clotting in unusual sites from COVID to a recently discovered syndrome – vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) – which has been linked to viral vectored (AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson) but not mRNA vaccines.

‘VITT has a higher published mortality of 55–60% from the German and Norwegian series compared to the 18–20% described in this report and is a syndrome with a constellation of findings which includes clotting in unusual sites … as well as a bleeding predisposition; patients are clotting and bleeding at the same time,’ she said.

‘Unlike COVID, it is challenging to diagnose VITT [as it requires] a high index of suspicion and specialised tests that are not always available, like CT or MRI scans, and antibody tests for confirmation.

‘This delay to diagnosis may well be contributing to poor outcomes.’

Dr Daryl Cheng, Medical Lead of the Melbourne Vaccine Education Centre, also noted some ‘methodological and applicability challenges’ associated with trying to compare the study’s data between COVID-19 disease and COVID-19 vaccines.

‘Firstly, the data sources were from different populations and countries and are not directly comparable. They were not matched for age or other confounding factors,’ he said.

‘Secondly, it is unclear what the background rates of CVT are in each of these populations. This means that it is not clear whether the reported higher rate of clots represents a true increase above an expected baseline rate of CVT or PVT in those specific populations.

‘Furthermore, comparing isolated CVT/PVT with thrombocytopaenia syndrome [TTS], the syndrome of interest following COVID-19 AstraZeneca vaccine, means we actually may be comparing two separate entities and drawing conclusions that are not entirely accurate.

‘There is not enough clarity within the existing study data to indicate whether there were other clinical signs and laboratory signals, like low platelets, to indicate that there was a TTS-like syndrome after COVID-19 disease.’

Log in below to join the conversation.

AstraZeneca central vein thrombosis coronavirus COVID-19 CVT Pfizer rollout vaccine

newsGP weekly poll

Health practitioners found guilty of sexual misconduct will soon have the finding permanently recorded on their public register record. Do you support this change?