Column

Giving patients a realistic understanding of IVF success rates

Dr Karin Hammarberg says patients need transparent, evidence-based information about what is possible.

A woman’s age is the most important determinant of the chance of a positive IVF outcome.

A woman’s age is the most important determinant of the chance of a positive IVF outcome.

More and more people in Australia are turning to IVF to have a baby.

The latest data from Victoria show that the number of women having IVF increased by 20% in the past year and the number of treatment cycles increased by 27%. So, more women are having more cycles.

While IVF has helped millions of people around the world have children, about half of those who try IVF don’t achieve their dream of a baby, and few have a baby after one cycle.

To help people who embark on IVF have realistic expectations, they need good information.

Unfortunately, IVF success rate figures on clinic websites are notoriously difficult to interpret – and one clinic can look much more successful than another because of the way they measure success.

It is important to know whether a clinic’s success is defined as a clinical pregnancy or a live birth, and whether the success rate figures are per started treatment cycle or per embryo transfer.

As an example, let’s say 100 women start a treatment cycle. Seventy-five of them have an embryo transfer, 25 have a clinical pregnancy and 20 give birth. The pregnancy rate per embryo transfer then is 33%. But the live birth per started treatment cycle is only 20%.

Regardless of how success is reported, the outcome is the same: of the 100 women who started a treatment cycle, 20 had a baby.

For most people, the ultimate chance of having a baby increases for each additional cycle, up until five cycles.

So, it’s helpful to have a series of treatments in mind rather than expecting immediate success when embarking on IVF. That way expectations may be more realistic, and people may be more likely to try again if treatment fails.

People also need to be aware that the woman’s age is the most important determinant of the chance of a positive IVF outcome. Age-specific cumulative live birth rates are the most helpful when discussing what to expect from IVF with patients.

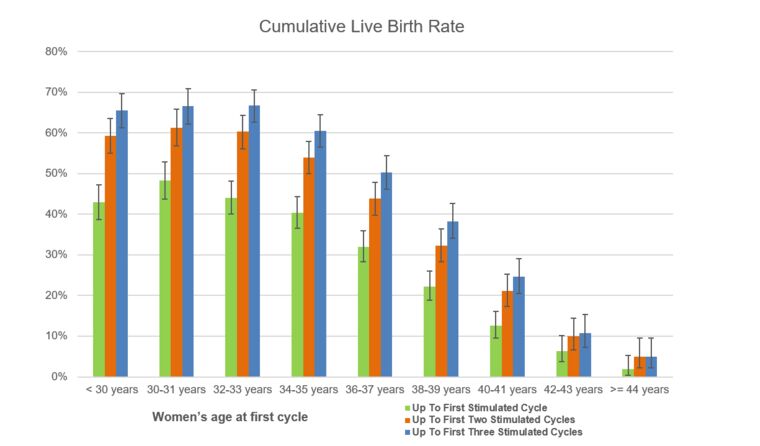

Data showing the cumulative live birth rate, released for Fertility Week, shows the proportion of people who have a baby after one, two or three stimulated IVF cycles, including all fresh and frozen embryo transfer attempts associated with these complete cycles.

The Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority (VARTA) developed a graph based on data from people tracked for 3–4 years, until 30 June 2020, illustrating cumulative live birth rates at different ages.

Age-specific cumulative live birth rates for one, two and three completed treatment cycles based on VARTA data. (Image: Supplied)

This shows that for women aged up to 30 years, the average chance of a baby was 43% after one stimulated cycle and 65% after three stimulated cycles. For women aged 42–43, the chance of a baby was 6% after one and 11% after three stimulated cycles.

Almost one quarter of women who have IVF are aged 40 years or older. They invest a lot of time and money for a minuscule chance of having a baby. For women in this age-group, using donor eggs from a younger woman might be a better option.

Research conducted in 2020 analysed data from all women aged 40 years and over who had IVF in Victoria between 2009 and 2016. Of these, 987 used donor eggs and 19,170 used their own eggs.

This study found that women who had used donor eggs were five times more likely to have a live birth than women who had used their own eggs.

People contemplating IVF need transparent and evidence-based information about what is possible with IVF to make well-informed decisions and have realistic expectations if they decide to go ahead.

GPs can support their patients by discussing age-specific cumulative live birth rates and the possibility of using donor eggs for women in their 40s when they refer them for IVF treatment.

For more evidence-based information about factors that affect fertility, visit the Your Fertility website.

Log in below to join the conversation.

donor eggs fertility IVF live birth rates

newsGP weekly poll

As a GP, do you use any resources or visit a healthcare professional to support your own mental health and wellbeing?