Feature

An all-but-forgotten use of biological killers may help beat superbugs

Bacteriophage viruses seek out and kill specific bacteria – even drug-resistant strains.

Phages are lethal against bacteria. Can they become clinically useful?

Phages are lethal against bacteria. Can they become clinically useful?

Sewage water samples from around Australia arrive at Monash University every three months.

Researchers blend the samples together to create a nasty cocktail. They then spike the mix with something that keeps doctors up at night – strains of bacteria most at risk of becoming multi-drug resistant.

They incubate the blend and leave it overnight, waiting for the next day to see what’s happened.

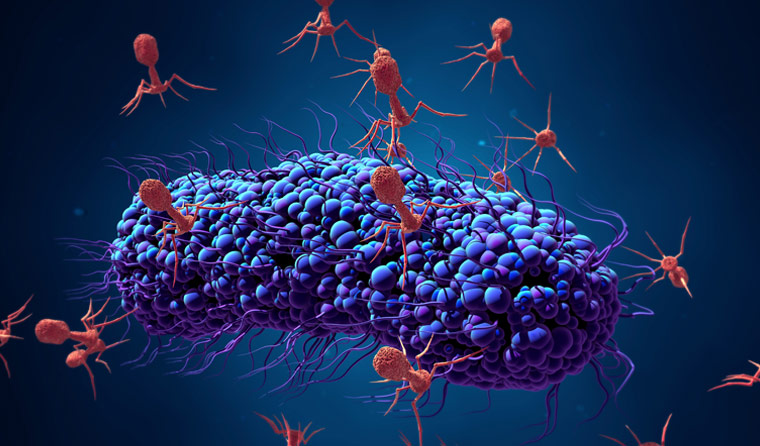

The bacterial population has usually taken a severe hit, burst open from within by bacteriophages, alien-looking hunter–killer viruses specialised to infect one specific strain of bacteria.

Turning the phage

Phages, as they are known, were discovered a century ago. Their discoverer realised their enormous potential as antimicrobial agents, and phage therapy was soon tackling lethal infections.

But when penicillin finally became widely available in the 1940s, doctors had a powerful antibiotic able to wipe out many different strains at once. Phage therapy – which was limited by the specificity of the viruses – all but disappeared from Western medicine.

Behind the Iron Curtain, however, phage research continued, to the point that you can buy over-the-counter phage therapeutics in Russia, Poland and the small republic of Georgia.

And as the world struggles to deal with the rise of multi or extensively drug-resistant bacteria – everything from hospital superbugs to the resurgence of old killers like tuberculosis – many think phage therapy may be a key plank in our efforts to control bacterial infections.

Monash researcher Dr Fernando Gordillo Altamirano told newsGP that phage therapy has huge potential to save lives.

‘As a medical doctor, I believe that few of my colleagues are aware of how much the field of phage therapy has grown over the last few years,’ he said.

Dr Gordillo Altamirano recently published Phage therapy in the postantibiotic era in Clinical Microbiology Reviews, outlining the rebirth of phage therapy, its potential, and challenges remaining.

‘When antibiotics were successfully introduced for widespread clinical use, everyone forgot about phages. The main reason is a specific phage can only kill a specific bacteria, or even a strain in that species,’ he said.

‘But with antibiotics, you can have an educated guess as to the species and take advantage of the wider spectrum of activity.

‘But now that antibiotics aren’t working anymore, we’re desperate to find new tactics and strategies against antimicrobial resistance. That’s the main driving force behind the rebirth of phages.’

A promising new use for phages is that as bacteria evolve to resist phages, they incur fitness costs such as impaired growth, reduced virulence – and re-sensitisation to antibiotics.

That, Dr Gordillo Altamirano said, means phages and antibiotics may be used in sequence.

‘Say we have a patient with a serious infection. We could administer phage therapy, which might work for two or three days until the bacteria becomes resistant. But by then, the chances are it will become re-sensitised to antibiotics. Then you administer antibiotics and eradicate the infection,’ he said.

In Russia, Poland and Georgia, the main obstacle to phage use – their specificity – has now been overcome by combining multiple phages.

‘In Russia, you can buy a cocktail of phages against gastroenteritis. Phage preparations are commercially available over the counter,’ Dr Gordillo Altamirano said.

‘When Western researchers decided to find out what’s in those preparations, they found up to 23 different phages.

‘So if we want to create a product effective against UTIs [urinary tract infections], we know from epidemiological data that in a normal patient with no underlying disease, there might be up to nine pathogens that cause almost all UTIs. So you create a cocktail of phages against all nine – and commercialise it.’

While phage therapy has become a routine part of medical practice in Russia, Poland and Georgia, Dr Gordillo Altamirano said regulations and guidelines are lacking in Western countries.

‘In Western countries, we have had many instances of phage application,’ he said.

‘The main route is compassionate use, patients with severe life-threatening infections, where antibiotics stop working altogether and doctors and families agree to try experimental therapy, with encouraging results.

‘But before we can dream of widespread use, there are two major issues. The first is we need a coherent legal framework. We can’t use the same legal framework as for non-living drugs, as we do for antibiotics. Phages are by definition organisms, so we would need a specific legal framework to use, preserve, manufacture and control them.

‘Secondly, there is an issue with intellectual property, because biological organisms cannot be patented. So how can we commercialise it? How can we make it available? If we want pharmaceutical companies to join this venture, we have to resolve that.’

A promising new use for phages is that as bacteria evolve to resist phages, they incur fitness costs such as impaired growth, reduced virulence – and re-sensitisation to antibiotics.

A promising new use for phages is that as bacteria evolve to resist phages, they incur fitness costs such as impaired growth, reduced virulence – and re-sensitisation to antibiotics.

Dr Jeremy Barr, co-author of Phage therapy in the postantibiotic era, runs the Barr Lab at Monash University, which explores the use of phages.

‘When people see pictures of them, they’re such alien entities. They’re amazing what they can do,’ he told newsGP. ‘They control bacterial populations, have a huge function in the microbiome and control many cycles in the oceans. They’re incredible entities.

‘[Phages] can even be used to revert superbugs back to their antibiotic-sensitive forms, an approach we are testing here.’

But Dr Barr predicted widespread use of phages in Australia is still five to 10 years away.

‘The big limiting factor is the lack of rules and regulations. I expect that to change soon [in the US] when the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] releases formal guidelines,’ he said. ‘When that happens, it will open the floodgates to companies, clinicians and researchers.

‘When the FDA does that, the Therapeutic Goods Administration will follow. We generally lag by a few years, so within 10 years I’d hope we will have active therapy using phages.’

While using biological organisms is still a way off, Dr Barr said phages have already contributed to a new method of controlling bacteria.

‘Lysins are the enzymes the phage uses to [break] the cell wall. Researchers have isolated that to use as a drug,’ he said. ‘These have shown really promising results and I think will be the next big thing, as they’ll act more like a drug.

‘Currently, we’re using them to kill gram-positive bacteria.’

Dr Barr said it is important for GPs to be aware that phages can already be used in compassionate use cases. He cited the famous case of American Tom Patterson, who was near death from a multi-drug-resistant systemic bacterial infection before being saved by a cocktail of phages.

‘That was a big success story. Tom was going to die, and then a team worked together to produce and purify phages,’ Dr Barr said.

‘GPs should be aware that this is a potential treatment right now, if you can access the phage community and have the right clinical team. You can get regulatory approval for compassionate cases.’

antibiotics antimicrobial resistance bacteria phages research

newsGP weekly poll

Health practitioners found guilty of sexual misconduct will soon have the finding permanently recorded on their public register record. Do you support this change?