News

An Australian quest for the new frontier of antibiotics

newsGP marks National Science Week by speaking with pharmaceutical chemist Dr Ernest Lacey about finding new antibiotics within Australia’s unique microbiome.

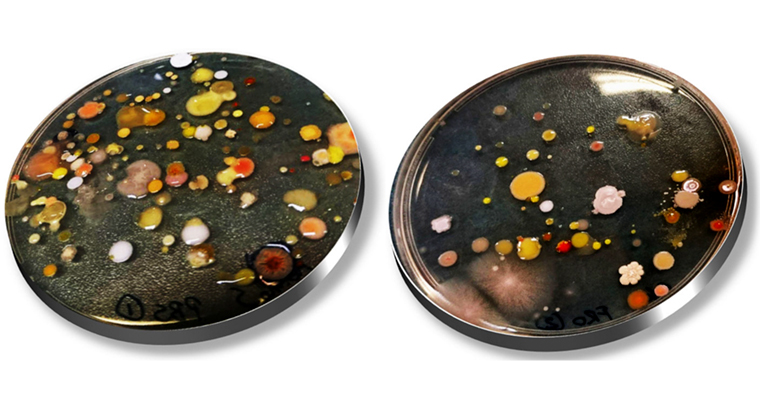

Pharmaceutical chemist Dr Ernest Lacey described these dark plates as ‘a glimpse of biodiversity in the microbial world’.

Pharmaceutical chemist Dr Ernest Lacey described these dark plates as ‘a glimpse of biodiversity in the microbial world’.

Antimicrobial resistance is a serious and growing threat to the health and wellbeing most people have come to take for granted.

‘It’s no longer a theoretical issue that people will die from bacterial diseases that were preventable 30 years ago – it’s a reality, and it will get worse,’ Dr Ernest Lacey, pharmaceutical chemist and Managing Director of Australian bio discovery company, Microbial Screening Technologies (MST), told newsGP.

‘It probably won’t affect our lifetime. It may influence our children, but our grandchildren are in deep trouble, because there is no wave of discovery that is coming up behind.’

In response to this problem, a comprehensive quest has been launched to search for new antibiotics within Australia’s microbiome, in the form of a three-year project named ‘BioAustralis, towards the future’ (BioAustralis).

The project, supported by a $3 million Co-operative Research Centres Projects (CRC-P) grant, involves a collaboration among scientists from Macquarie University (MU), the University of Western Australia (UWA), Advanced Veterinary Therapeutics (AVT) and Dr Lacey’s company, MST.

A key solution to the dwindling effectiveness of the existing stock of antibiotics is the development of new ones. However, a major barrier to implementing this solution has been the lack of financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies to carry out discovery work.

‘If you look at the patent literature, it is a safer financial investment to change the chemical structure of an antibiotic on the market and develop that as a drug; you get the same level of patent protection as if you were to discover something completely novel,’ Dr Lacey said.

Such modifications are known as ‘me too’ drugs, but they present their own problems.

‘For instance, we don’t just sell erythromycin, we sell a whole lot of semi-synthetic derivatives of it, all of which are elegant in their own way, but all function by the same mode of action,’ Dr Lacey explained. ‘So when resistance emerges, it emerges to all of the “me too” analogues,’.

Dr Lacey believes the CRC-P collaborative funding model is a good way to counter this problem in the endeavour of discovering antibiotics, and one that has a strong chance of success.

‘[CRC-P grants] are well-structured and are focused on single outcomes in defined fields,’ he said.

‘Our collaborators are the people that we need to help solve the problems that we can’t resolve ourselves.

‘Three years is not a long time, but with a targeted project, you can get a long way.’

MST’s contribution to the project is its vast library of Australian microbes – more than 500,000, sourced from the nation’s soil, plants, insects and animals.

‘Australia’s microbiome was, in effect, a completely untapped resource,’ Dr Lacey said, describing what drove him to leave his previous job at the Commonwealth Scientific Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and form MST.

‘We had looked at trees, we had looked at algae, we had looked at lichens – macroorganisms – and we had a very strong history of research in this area dating back to the post-war period, both in CSIRO and in the university system.

‘But in terms of looking at microorganisms, there may have been 25–30 papers on the subject. And yet, microorganisms were where the bulk of the new drugs were being discovered; something like 60% of the drugs currently on the market owe their origins to natural products and most of them to microbial metabolites.’

MST’s library heralds the return of microbial discovery work in nature, after a long period of focus within the pharmaceutical industry on synthetic products because they were faster and cheaper. But, in Dr Lacey’s opinion, not as efficacious.

‘The problem with synthetic is that it’s untested in nature – man-made chemistry is a random act. In effect, you are testing something in the hope that it will work,’ he said.

‘And this situation has evolved in which we simply ran out of man-made chemistry, so we have moved back to looking at nature for the original leads.

‘The beauty about our compounds is that every single one produced by a microbe has a function. We may not know what that function is, but when they’re producing a hundred different chemical structures, each with a role within that organism or between one organism and another, you’re able to see that you’re testing, not only bio-diversity, but chemical diversity.’

After MST provides the raw material, its BioAustralis collaborators will carry out further work to develop its potential.

‘Each microbe contains a unique cocktail of metabolites,’ Dr Lacey said. ‘When we find an interesting new molecule, we’ll be relying on MU researcher Dr Andrew Piggott and his team to help us to work out its structure and mode of action.

‘Then Dr Heng Chooi from UWA will use genomics to unravel how the microbes assemble these metabolites and then boost their productivity.

‘Advanced Veterinary Therapeutics is led by Dr Stephen Page and will focus on animal health potential.’

With its focused funding, collaborative approach and quarterly reviews to check on its progress, Dr Lacey is optimistic that the BioAustralis project will deliver.

‘There are so many hurdles in developing a drug, you couldn’t list them,’ he said. ‘But unless people are prepared to take a chance on looking for new things, the alternative is pretty ugly.

‘CRC-Ps are a good way of the government funding research with industry because they are a tight grant with a start date, a finish date, and the expectation there will be a product at the end of it. We feel that making substantial progress quickly is a good fit with the CRC-P system.

‘We have many interesting microbes we can take from our existing collection and work on at the drop of a hat. Many of the chemicals we are looking at in this study, if we don’t already have them in bottles ready to test, we have them only a month or two from it.

‘I am certain that we will get there.’

Antibiotics Antimicrobial-resistance National-Science-Week

newsGP weekly poll

Which of the following areas are you more likely to discuss during a routine consultation?