Interview

Q&A: Antimicrobial resistance is still on the rise – but are GP prescribing practices to blame?

The use of antibiotics may be plateauing, but it is not declining. newsGP speaks with two experts about what else can be done.

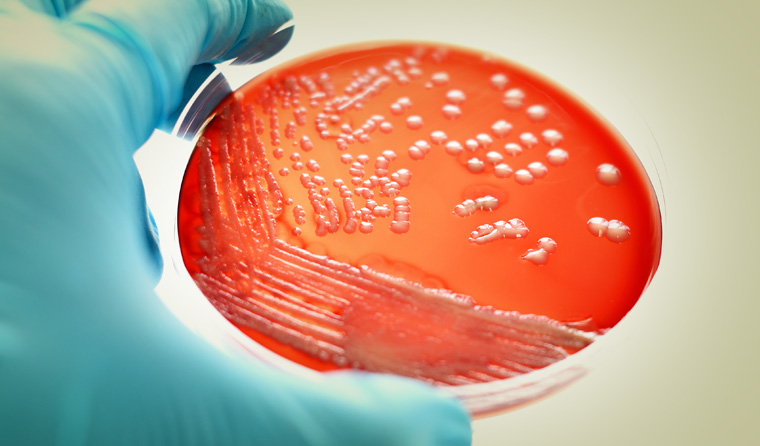

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and other resistant bacteria are becoming a major health problem.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and other resistant bacteria are becoming a major health problem.

The World Health Organization this year declared antimicrobial resistance to be one of the major threats facing humanity, with up to 10 million annual deaths possible by 2050 if drug-resistant bacteria are not addressed.

Given the time it takes to bring new antibiotics to market, many experts have been calling for a reduction in prescribing to prolong the usefulness of current drugs.

In May, a major report from Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Australia found antibiotic use had declined for the first time in two decades between 2015 and 2017. But the report also found antimicrobial resistance ‘shows little sign of abating,’ posing an ongoing risk to patient safety.

More than 10 million Australians had at least one antibiotic prescription dispensed in 2017.

‘[A]lmost half the samples of enterococci tested across Australia were resistant to the antibiotic vancomycin – a level higher than seen in any European country, [and] community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] has become the most common type of MRSA infection, particularly in aged care homes and remote regions,’ the report stated.

‘Of particular concern is antibiotic prescribing for acute bronchitis and influenza, for which antibiotics are never recommended. A remarkable 92% of patients aged 18–75 years with acute bronchitis and more than half of patients with influenza were prescribed an antibiotic.’

Dangerous bacteria like E. coli, salmonella, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis are becoming ‘increasingly resistant’ to major classes of drug, with some now resistant to the antibiotics kept as the last line of defence, according to the report.

Australia’s antibiotic prescription rate remains high by international standards, with 23.5 defined daily doses per 1000 people as of 2015, higher than the OECD average of 20.6.

But is overprescribing in primary care really the cause for this emerging issue? What are the other contributors? And what more can be done?

To find out, newsGP spoke to Dr Mina Bahkit, and GP and Professor of Evidence-Based Practice Paul Glasziou, both from the Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare at Bond University.

How much responsibility falls on prescribing in primary care?

Professor Glasziou:

The answer is we don’t know yet. Our best guess would be 40% hospitals, 40% GPs and 20% aged care.

We do know that infectious disease specialists are seeing more and more cases with community-acquired infections that have multi-drug resistance, forcing them to use the last line of antibiotics.

What role does the use of antibiotics play in agriculture? Is that a major cause in Australia?

Professor Glasziou:

No. The major cause is the use in humans.

The regulations are quite strict here, so [agricultural use] is a pretty limited problem. But it is a big problem in other countries. There is some illegal use we know about, but it’s a minor issue.

Overall, the total evidence [linking use in animals to human antimicrobial resistance] is weak. That’s because you need to do a lot in animals before it flows through to humans. The resistant bacteria have to be transmitted through farm workers to someone else.

Dr Bakhit:

One study last year found that reducing antibiotic use in food animals does reduce antimicrobial resistance in animals, but there is less evidence for the link to reducing antimicrobial resistance in humans.

What are some emerging solutions?

Dr Bakhit:

We know that prescribing antibiotics for acute respiratory infections is of very little benefit. So there’s one strategy we are promoting, which is delayed prescribing.

When you’re not sure if it’s a bacterial or viral infection, a GP can give the patient an antibiotic prescription and ask them to wait three days to see if it gets worse or better. If it gets worse, they can use the prescription.

In my doctorate, I examined whether shared decision-making between doctors and patients can help tackle antimicrobial resistance. I found that when GPs used patient decision aids, discussions of the benefits and harms of antibiotics happened more often and in more detail.

‘Infectious disease specialists are seeing more and more cases with community-acquired infections that have multi-drug resistance, forcing them to use the last line of antibiotics,’ Profeessor Paul Glasziou said.

Is antimicrobial resistance reversible?

Professor Glasziou:

Reversibility is one of those things that most people are not aware of. If we decrease the number of antibiotics being used, we do get back those antibiotics to some degree.

We don’t know how reversible antimicrobial resistance is, but we do know there is a degree of it.

In animal husbandry, it has been shown that when you stop using antibiotics, resistance drops. That’s because it’s a numbers game.

To fight antibiotics, bacteria have to carry an extra ‘armoury’. But if there’s no threat, it becomes a disadvantage because it’s extra genetic weight they have to carry.

We do know, however, that the selection pressure to get resistance to antibiotics occurs much faster than the pressure to lose it. That’s because the pressure to lose it is a very small selective pressure. But it does occur.

Are there signs of progress?

Professor Glasziou:

Antibiotic use in primary care has been going up steadily since around 2003. After campaigns by NPS Medicinewise there was a plateau, but there hasn’t been a real decline. Their impact has been no further increase in use, rather than an actual decline.

The letters sent by the Chief Medical Officer to high-prescribing GPs led to a 10% dip in their antibiotic prescribing, with a persistent decline for at least six months afterwards.

What we really need is a Swedish-type program, where campaigns aren’t just one-off but every year, to keep antibiotic use down.

If we ignore the problem, it becomes whack-a-mole – it keeps coming back.

In Sweden, they’ve had a 20-year program leading to a gradual decline each year. In Australia, we haven’t had a sustained, well-resourced program focusing on antimicrobial resistance in primary care. There have been intermittent attempts, not sustained.

Do patient expectations play a role?

Dr Bahkit:

Yes. It’s from both parties.

Some patients expect antibiotics from GPs. That’s why we suggest the delayed prescription, advising people to wait until they know they need it. If GPs don’t communicate around antimicrobial resistance, it can be hard for patients to know about the issue.

We want to increase patient awareness of the potential harms of using antibiotics.

Professor Glasziou:

It is common that GPs misread patient expectations. Doctors may think their patients are sitting there wanting antibiotics, but they’re often relieved that they don’t need them.

That’s not always true, of course, and there are patients who are really insistent and will go doctor-shopping to get them.

How can GPs frame the possible harms of antibiotics?

Professor Glasziou:

There are a lot of possible harms. There are risks of immediate adverse events such as diarrhoea, or more rarely even Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Longer term, there is the disruption of the gut microbiome, which is prolonged.

There’s also the issue of personal antimicrobial resistance. Community resistance is the sum of individual resistance. That means you can personally have antimicrobial resistant bacteria for a period. And that means if you get a serious infection, antibiotics are less liable to work.

Let’s say a patient takes antibiotics for a cold and then gets pneumonia. That means the antibiotics for pneumonia are less likely to work.

Many patients are not aware that resistant bacteria can be transmitted between family members. So if you have resistant bacteria and pass them on, antibiotics are less likely to work for your family members.

There is also the epidemic threat as well, with new resistant strains of, say, multidrug-resistant staph coming in from overseas. It’s not the same as the flu, which can go across the whole country – bacteria are slower, and the epidemic may die out.

Dr Bakhit:

Antimicrobial resistance affects everyone. It’s a real threat and the transmission of resistance in the community will lead to more severe infections.

It makes sense to focus on prescribing in the community because there’s a huge amount there.

What should patients know about antimicrobial resistance?

Professor Glasziou:

From a self-interest point of view, the more courses of antibiotics you have, the more likely you as an individual will run into a problem with an infection or during elective surgery.

We’re wasting our ammunition by using antibiotics when we don’t need them. That’s from both an individual and public perspective. We need to reserve them for when they’re really needed to help us.

Dr Bakhit:

In a recent study, my colleagues and I found that patient understanding of the nature of resistance is poorly understood.

We found that antimicrobial resistance was seen as a problem for the future, and one affecting the community, with little understanding of the impact on individuals or the contribution made by individuals. We also found few patients knew that resistance can decay with time.

Login below to join the conversation.

antibiotics antimicrobial resistance primary care

newsGP weekly poll

As a GP, do you use any resources or visit a healthcare professional to support your own mental health and wellbeing?