Opinion

General practice education is not the universal solution

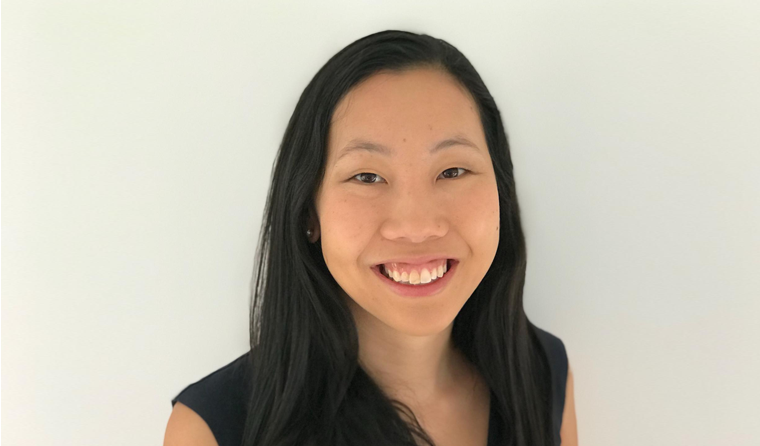

GP and researcher Dr Melinda Choy questions whether reliance on general practice education is effective – or drowned out.

Is general practice education always the answer? ANU researcher Dr Melinda Choy says maybe not.

Is general practice education always the answer? ANU researcher Dr Melinda Choy says maybe not.

Everyone wants to educate GPs. There is a pile of advertisements in my practice lunchroom from the local primary healthcare network, the RACGP, local hospitals, specialists and of course, the drug companies. Pinging into my email inbox are hundreds – even thousands – of modules, webinars and e-audits that I can do to improve my practice.

While I do, of course, want to continually update my practice and I am committed to the principle in medicine of lifelong learning, sometimes I wonder whether all the researchers, advocacy groups, companies and people who want to educate us realise that they are all trying to do it at once. It’s a crowded market.

I get where they are coming from. There are many significant public health issues requiring a coordinated approach. GPs are at the coalface of patient care, and there are many of us. If you scale up a general practice education initiative, it stands to reason you could help a large number of patients.

So I can understand why it is easy to recommend education as a policy. But I have to ask – should it really be the default go-to solution for every public health issue?

I’ve come across several recent examples that make me think – perhaps not.

Take the recent announcement by Health Minister Greg Hunt to pledge $6.8 million to the better understanding and management of chronic pain, following the release of The cost of pain in australia, a report by Deloitte Access Economics and funded by Painaustralia, a consumer advocacy group. It is good news and helps tackle an important health issue in Australia. Most of the funding will go towards improving access to pain management services for rural Australians, and some will go towards improving consumer and public awareness and education.

That’s fine.

But what I question is the $1 million allocated for a nationwide general practice education program to enable GPs ‘to participate more effectively in pain management care’.

The premise of this recommendation in the Deloitte report starts with three trials of varying quality, a few of which showed an improvement in line with best practice pain management, but no overall decrease in opioid prescribing volume.

Then, US Centre of Disease Control (CDC) data showing a drop in opioid deaths with a drop in opioid prescriptions was extrapolated to say that Australian opioid-related deaths could potentially be reduced with a general practice education program.

Essentially, the recommendation that a general practice education program to reduce opioid-related costs and harms, including overdose-related deaths, is based more on hypothetical calculations and assumptions rather than high quality trial evidence.

So will this really work the way it is promised to work? The evidence is distinctly mixed on whether general practice education interventions are effective in changing patient outcomes.

For instance, a systematic review and meta-analysis of whether general practice training in depression care affects outcomes, published in 2012, looked at 11 studies and found that provider training on its own did not seem to improve depression care.

Further, a 2014 systematic review published by Australian Family Physician into online continuing medical education (CME) for GPs found there was little evidence for the impact of CME on patient outcomes.

By contrast, an Implementation Science overview of reviews published in 2017 suggested some benefit for patient outcomes from physician education interventions.

So what can we conclude? There is some evidence that carefully controlled trials of general practice education interventions can change some patient outcomes. But that does not necessarily equal an effective go-to policy in the real world.

Rather than relying on medical education as the panacea, I think we need to think more broadly about effective measures for change.

I feel that many producers of educational interventions – whether economists, researchers, public health campaigners, advocacy groups or the government – need to recognise the context that their education interventions are going into.

Education – which by its nature has to be broad – can be rendered useless if we do not understand the context.

Put simply, efforts to educate my patient who has been smoking for 20 years about the risks and benefits of smoking while she is in the middle of a crisis at work will fail.

Does the specialist who wants GPs to better manage their one condition of interest know that his education intervention is yet another colourful flyer in the tea-room and his seminar is at the end of another long day?

I wonder if he realises that we see many patients, each with their own interacting conditions. His view of how to treat his isolated condition of interest might not apply as universally to each of them as he imagines. General practice is valuable because we care for whole people in all their complexity.

Though we may not provide as high quality care for a specific disease than specialists, general practice and primary care are associated with better health and value for both the individual patient and population. Does the specialist understand that I am actually caring well for the patient with his condition of interest, even if I am not technically treating the condition perfectly according to guidelines?

But if the government really does think that general practice education interventions are one of the best ways we can save and improve lives, why not subsidise two working hours a week for every GP to be educated, instead of leaving it up to us to claw out time from our personal lives? Many hospital-based specialists are allocated annual funding for professional education.

Or perhaps we can think more broadly and creatively about how to create change and improve patient outcomes.

After all, the Nuffield ladder of intervention with eight steps ranks education as only one step above doing nothing, and offers six other categories of higher level interventions to guide and enable better choices. One of these higher categories involves restricting choices, and the upscheduling of codeine is a good example of another way to reduce opioid use without increasing opioid prescriptions.

Other options include environmental and system restructuring – I’m watching the slow development of a consistent national real-time prescription monitoring system, which will improve my ability to make more informed and safer decisions when prescribing high-risk medicines.

We could also look at nudge theory, the behavioural economics approach at the centre of the 2017 Nobel Prize for Economics, which proposes positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions as effective methods to influence people.

Some of these other interventions are more cumbersome to implement than another general practice education module, but if they are proven to be more effective, then surely they are worth it.

Because while general practice education has an important role in our health system – to support GPs in providing high quality whole-person care for our patients – it should not be over-relied upon as a go-to tool for experts to improve public health issues.

continuing professional development general practice education

newsGP weekly poll

Which of the following areas are you more likely to discuss during a routine consultation?