Earlier this year, then–Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced that general practice bulk-billing rates in Australia had reached an all-time high of 85.8%.1 While such a high rate of bulk-billed general practice services – where appointment costs are charged directly to the Commonwealth with no cost to the patient – is a commendable achievement, access to these services is not equally distributed across Australia. Importantly, the aim of achieving equitable access to bulk billing for those living in rural and regional Victoria has not yet been met, and may be under increasing pressure.

Australians who live in rural areas, encompassing those living in regional and remote areas, typically experience higher degrees of socioeconomic disadvantage and poorer access to health services than Australians residing in major cities.2 Bulk-billing services are crucial to enable access to healthcare for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients in particular; however, previous research has shown that general practice bulk-billing rates are lower in regional areas that have the greatest need for these services.3 Higher bulk-billing rates have been proposed to be positively associated with the density of general practices in a given area (with the associated increased competition) and higher general practice caseloads,4 and each of these factors may be contributing to the lower rates of bulk billing in rural and regional Australia. It must be noted, however, that rural communities are diverse in terms of their health and disease profiles, health behaviours and health service access.

Prevalence of chronic disease is typically higher in rural Australia than in major cities, and health outcomes are often poorer.5 A recent report found that patients with at least one chronic disease account for 51–66% of rural and regional general practice consultations,6 and consultations for chronic disease may be longer and more complex than standard appointments. This report suggested that bulk-billing clinics are turning away patients who were requiring longer consultations, as these consultations are becoming financially unviable.7 In rural areas, increased rates of complex cases without a concomitant increased rebate places further strain on the bulk-billing clinics, and consequently affects access to care for patients with complex needs, including patients with chronic disease and patients with poor mental health.7 During his time as the vice president of the Australian Medical Association, Dr Tony Bartone stated, ‘There is a need to ensure that Medicare remains robust enough to ensure it is equitably accessed by those in community most in need’.8

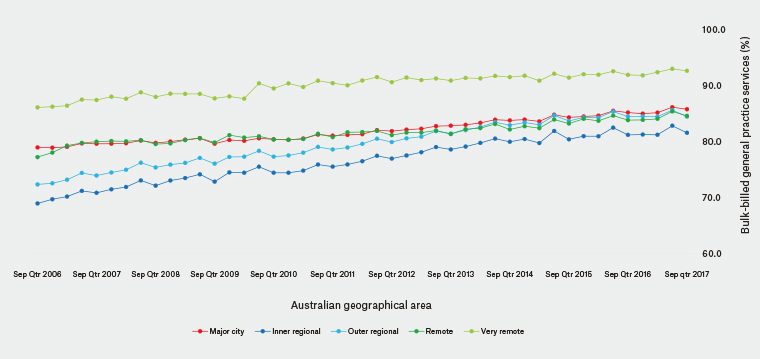

Publically available data suggest that although bulk-billing rates have consistently increased throughout Australia over the past 12 years, the rates in inner regional areas remain lower (81.6%), compared with major cities (85.8%), outer regional areas (84.5%) and remote areas (remote 84.6%, very remote 92.7%; Figure 1). 9 Rates of bulk billing also vary within individual regional Primary Health Networks. For example, the Murray Primary Health Network (MPHN) in regional Victoria, which encompasses the authors’ university Department of Rural Health sites, spans almost 100,000 square kilometres from Mildura to Albury and is primarily inner and outer regional. Within the MPHN there are 12 districts of general practice workforce shortage, including Wangaratta.10 Numbers of bulk-billed general practice services across the MPHN are lower than the national average.10 In some inner regional areas of the MPHN, rates of general practice bulk billing are below 70% (eg 69.2% in Wangaratta and Benalla).10 Access to bulk-billing clinics may be even more constrained for new patients in rural areas.11

Figure 1. Rates of bulk-billed general practice services by Australian geographical area. Data sourced from annual Medicare Benefits Schedule statistics.9

Although vulnerable communities exist in metropolitan areas, vulnerable patients residing in rural areas with low rates of bulk-billing general practice services may need to travel substantial distances to access bulk-billing services, or may forego or delay necessary general practice appointments. Vulnerable people may turn to emergency departments or other services that do not require co-payment. Bulk-billing regional clinics providing low-cost access to some specific services – for example, women’s health services – provide an avenue for patients who would otherwise be compelled to travel to metropolitan areas, incurring substantial costs. However, these services may diminish without support for general practice providers.12 Performance indicator data track patients who report not being able to see a general practitioner when they needed to because of cost.6 Within the MPHN region, 4.9% of people reported having delayed or foregone a general practice appointment because of cost in the previous 12 months in 2015–16, though this had improved from 8.8% in 2013–14 and 9.0% in 2014–15.6

In summary, bulk-billed general practice services may be geographically variable. The financial viability of bulk-billed general practice services appear to be under increasing strain, and this is likely to affect patients with complex needs and the delivery of specific services. These issues may be exacerbated in rural areas. Further research is required to examine the key drivers of regional bulk-billing variability and the associated consequences for vulnerable patients. It is our contention that inequity of access to bulk-billed general practice services needs to be addressed to improve access for vulnerable patients in rural and regional Australia. This may be achieved by increasing incentives for regional general practice bulk billing and rebates for consultations for patients with complex needs.

†Deceased 8 December 2018.