Substance use disorder (SUD) is the persistent use of drugs (including alcohol and tobacco) despite serious harms and negative consequences associated with their use.1 The burden of disease associated with alcohol, tobacco and other drug use is significant. Harms include not only hospitalisation and death but also development of chronic disease, worsening mental health, suicide, overdose, pregnancy complications and injection-related harms.2 In 2019, 11% of the population smoked cigarettes, with an increasing number of people using e-cigarettes and vaping (8.8% to 11.3% between 2016 and 2019).3 Approximately 43% of the population have used an illicit drug in their lifetime, and 16.4% had used an illicit drug in the past year.3 It was estimated in 2015 that 2.7% of the burden of disease in Australia was due to illicit drug use.4

There is significant overlap between SUDs and chronic physical and mental illness, and comorbidity is common.5 The role of lifestyle interventions in mental health illnesses has previously been discussed, with evidence showing that lifestyle interventions – such as nutrition, movement, sleep, stress management and substance cessation – are efficacious and cost-effective therapies that improve mental health, physical health and quality of life.6 This article aims to explore the evidence regarding lifestyle interventions as either primary interventions or adjuncts to existing treatments for individuals with SUD.

Lifestyle medicine is defined as ‘the application of environmental, behavioural and motivational principles, including self-care and self-management, to the management of lifestyle-related health problems in a clinical setting’ (Box 1).7

| Box 1. Lifestyle interventions adapted from the six pillars of lifestyle medicine |

- Adopting a nutrient-dense, territorial eating pattern (eg Mediterranean and Okinawan ‘diets’)

- Optimising and individualising physical activity plans

- Improving sleep

- Managing stress with healthy coping strategies

- Forming and maintaining relationships

- Ceasing tobacco use

|

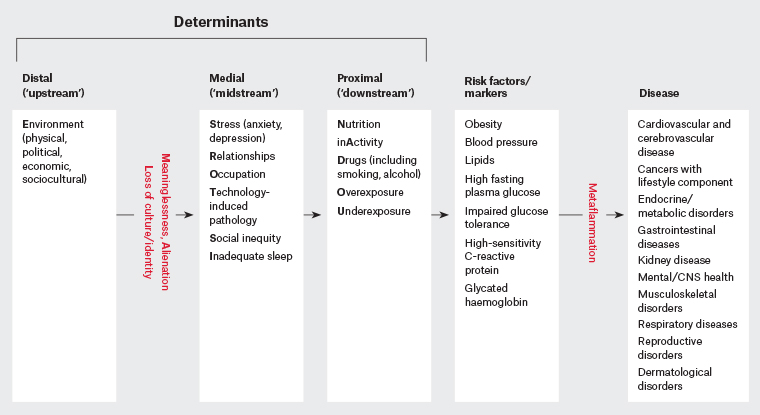

In Australia, Egger includes concepts such as meaning, cultural connection and social and ecological determinants of health (Figure 1).8 The field continues to grow its understanding and application with research in the fields of nutritional medicine, mind–body medicine, behavioural science, digital health and new models of care informing the scope and practice of lifestyle medicine.

Figure 1. A hierarchical approach to chronic disease determinants. Click here to enlarge.

CNS, central nervous system

Reproduced with permission of The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners from Egger G, Lifestyle medicine: The ‘why’, ‘what’ and ‘how’ of a developing discipline, Aust J Gen Pract, 2019;48(10):665–68.

Physical activity

Exercise may be an effective adjunctive treatment for SUD, especially given its safety profile and broad positive effects, including its ability to improve quality of life.9 Physical activity and other lifestyle-based treatments may alleviate symptoms of substance withdrawal such as irritability and restlessness.9 A 2014 meta-analysis indicated that physical activity (particularly moderate- and high-intensity aerobic exercise) may increase abstinence rates and ease withdrawal in those with SUDs,10 and this included studies of patients with opioid, alcohol and tobacco use disorder or polydrug use. However, a 2019 Cochrane review concluded ‘there is no evidence that adding exercise to smoking cessation support improves abstinence when compared with support alone, but the evidence is insufficient to assess whether there is a modest benefit’.11 Both studies commented on the lack of robust data, the biases inherent in the studies included in their analyses and lack of uniformity in how exercise programs were implemented.

Sleep

Poor sleep quality and quantity is a recognised risk factor for SUD and a common complication of substance use and withdrawal, with chronic substance use affecting sleep physiology, sleep–wake cycle and neurotransmitter activity.12 Disordered sleep in late childhood and early adolescence is an important risk factor for the development of SUD in later life.13,14 The most common sleep-related complications associated with SUD are insomnia, circadian rhythm abnormalities and sleep-related breathing disorders.14 The impact of poor sleep on patients with SUD increases the severity of SUD, decreases quality of life, worsens comorbid psychiatric conditions and increases suicidal behaviours and psychosocial problems.15

Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi) for people with alcohol use disorder has been shown to lead to improvements in sleep quality and daytime function as well as decreasing use of sedative medication to aid sleep; however, it had no impact on long-term relapse to alcohol.12 CBTi has shown some promise as an intervention to improve sleep in other drug disorders, but further high-quality research is required.15

Stress management and development of coping strategies

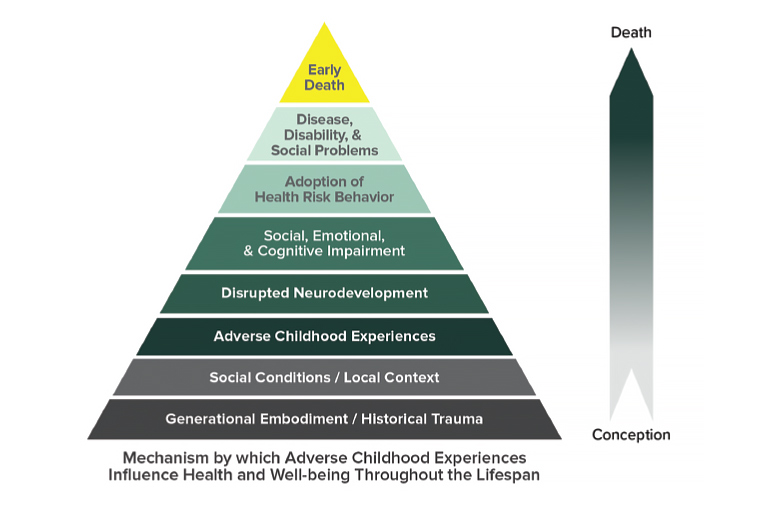

People with SUD have higher rates of mental health illness, maladaptive coping styles and emotional dysregulation than the general population.16 Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; Table 1) and emotional abuse have been associated with an increased lifetime risk of mood and anxiety disorders, avoidant coping behaviours and increased risks of developing SUD (Figure 2), with identification and effective treatment of the mood and anxiety disorder helpful in reducing the risk of development of SUD.17,18 Supporting people with SUD to further develop their coping and emotional regulation through techniques such as dialectical behavioural therapy strategies has been shown to decrease rates of emotional dysregulation and severity of alcohol use disorder and co-occurring SUDs.19 Specific early intervention regarding ACEs is within the remit of general practitioners, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention providing the Preventing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the best evidence guidelines, which can be used for early intervention of ACEs.20

| Table 1. Types of adverse childhood experiences20 |

| Abuse |

Household challenges |

Neglect |

- Emotional abuse

- Physical abuse

- Sexual abuse

|

- Mother treated violently

- Substance abuse

- Mental illness

- Parental separation/divorce

- Incarcerated household member

|

- Emotional neglect

- Physical neglect

|

Figure 2. The ACE Pyramid

Reproduced from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention20

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have shown efficacy in reducing the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in individuals seeking treatment.21 Although MBIs may improve quality of life and mood, a 2021 meta-analysis revealed uncertain benefit of MBIs in SUD-related treatment outcomes specifically.22

Comorbid tobacco cessation

Tobacco use and smoking rates are higher in those with SUD than in the general population. Oftentimes it is thought that smoking cessation interventions in those who are seeking treatment for other SUDs will have a negative impact on treatment outcomes. However, the evidence suggests that smoking cessation interventions in people with co-occurring SUDs does not lead to worsening substance use outcomes or increased relapse rates.23,24 Quitlines, particularly those that involve call back counselling, have been shown to improve smoking cessation rates.25

Diet and nutrition

People with SUD frequently have nutritional deficiencies, and poor nutritional status may affect the ability of people with SUD to resist substance use.26 For example, alcohol use disorder is associated with decreased nutrient absorption, leading to thiamine deficiency and Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome27 as well as other nutrient deficiencies such as deficiencies in magnesium, riboflavin, niacin, selenium, zinc and vitamins A, C, D and K.28 Multidisciplinary input – including patient education, individualised dietary and nutritional plans and periodic nutritional review – is associated with sustained improvement in nutrition among people with SUD.28,29

Relationships

Social isolation and loneliness are of significant concern in people with SUD, with studies showing 69% of people with SUD feeling that loneliness was a problem and 79% reporting feeling lonely in the previous month.30 Loneliness in patients with SUD is also correlated with increased rates of substance use.31 This is consistent with data regarding the importance of strong social relationships for health and mortality, with people with SUD in strong social relationships and within a community having a 50% increased likelihood of survival when compared with those who are more marginalised and socially isolated.32

Peer-led recovery is a hallmark of many behavioural relapse prevention strategies for people with SUD. SUD can break down social structures and relationships because of aberrant behaviour, stigma, social isolation or the addiction taking primacy over other social obligations. Reintegrating people with SUD back into a supportive community is important for recovery. Group and social interventions such as Alcoholics Anonymous or manualised 12-step framework interventions may be more effective than other established treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy for the maintenance of abstinence from alcohol.33 Increasing evidence suggests peer recovery support services can have a beneficial impact across a number of different SUD treatment service settings.34 People with SUD have stated the most important factor in achieving and maintaining abstinence was peer recognition or a caring and supportive relationship with a service provider,35 and this feeling of social support was associated with abstinence-specific self-efficacy.36

Behavioural change

General practice plays an important part in developing therapeutic relationships with, assessing and managing people with SUD. However, within Australian general practice, clinical treatments related to preventive activities such as nutrition and weight, exercise, smoking, lifestyle, prevention and/or alcohol were together given at a rate of only eight per 100 encounters (of which 0.6/100 were for smoking and 0.4/100 were for alcohol).37

There is reasonable evidence for a number of behavioural strategies – including brief interventions, motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioural therapy, relapse prevention strategies and contingency management strategies – for various SUDs.38

Discussions about minimising harm and reducing the risks associated with substance use is important, as abstinence may not be a goal or viable option for some people with SUD. Discussions with patients about needle and syringe programs, injecting techniques for people who inject drugs and overdose prevention strategies all serve as potential behavioural interventions to aid patients with SUD.

Conclusion

To more effectively support people with SUD, health services need to continue evolving to provide management options inclusive of evidence-based behavioural science. Growing evidence and theoretical understandings suggest lifestyle medicine interventions may be effective, in particular in the fields of social connection, physical activity and supporting behaviour change through established techniques. However, all domains require more high-quality intervention research. Given this, along with a strong safety profile and its beneficial effects on many mental and physical health conditions, the use of lifestyle medicine in SUD care should strongly be considered.