Anxiety disorders are among the most common psychiatric presentations in general practice, with a lifetime prevalence of more than 30%.1 They typically have their onset early in life and are associated with psychiatric comorbidity in many cases.2 Although evidence-based treatments for anxiety such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are effective for many patients, the most recent meta-analyses suggest that remission is only achieved in 60% of patients receiving CBT and/or SSRIs.3,4

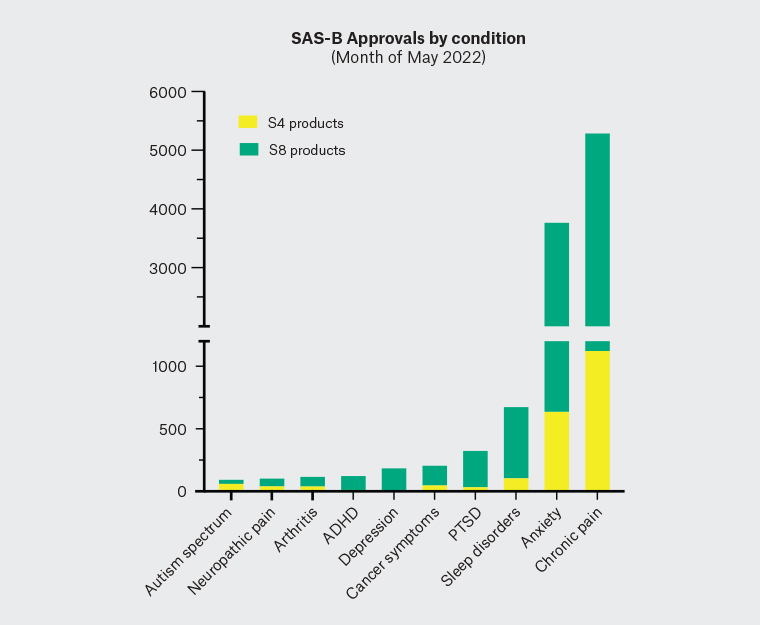

There has been a recent surge in scientific interest and media attention around therapeutic applications of medicinal cannabis products. Anxiety disorders are the second most common reason for prescribing such products in Australia, surpassed only by chronic pain (Figure 1).5 At the time of publication, Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) Special Access Scheme Category B (SAS-B) approvals for prescribed medicinal cannabis products are accumulating at approximately 12,000 per month, with more than 4000 of these for the treatment of anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Figure 1).6 This does not include an increasing number of additional medicinal cannabis prescriptions being issued under the Authorised Prescriber scheme.

According to the National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, more than 600,000 Australians use cannabis for medicinal purposes annually. However, at the time of that survey, only 3.9% were obtaining medicinal cannabis via legal pathways, with most sourcing their cannabis illegally.7 More recent estimates suggest that approximately 100,000, or one in six patients, are now receiving prescribed medicinal cannabis.8 In a recent survey of Australians (n = 1331) self-medicating with (mostly illicit) medicinal cannabis, anxiety was the most common ‘main condition’ being treated (12.6% of cohort), ahead of back pain (10.1%), depression (8.5%) and insomnia (7.1%). Approximately one-third of the cohort cited anxiety as one of several conditions they were self-medicating with cannabis.9

Given the increasing interest in and use of cannabis and medicinal cannabis products in treating anxiety, it is important to carefully review the rationale for the use of medicinal cannabis for treating anxiety disorders and current evidence regarding efficacy and safety. The aim of this article is to provide a concise summary of the available evidence.

The endocannabinoid system

A rationale for the use of medicinal cannabis for anxiety comes from consideration of the endocannabinoid system (ECS). The ECS is a ubiquitous biological system that regulates numerous physiological processes, with a major impact on sleep, mood, appetite, cognition and immune function.10 Components of the ECS include two primary receptors (CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors), lipid signaling molecules known as endocannabinoids (eg anandamide and 2-AG) and their synthesising and degrading enzymes.11 In the central nervous system (CNS), CB1 receptors provide a fundamental homeostatic mechanism governing neurotransmitter release and neuronal excitation.11 CB2 receptors are primarily located in the peripheral immune system but are also found in the CNS on microglia, with a key role in neuroinflammation.12

Preclinical research indicates that the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-AG can profoundly modulate fear and anxiety via their actions on CB1 receptors located in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex.13 Medications that elevate endocannabinoid concentrations via inhibition of the enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) have shown early signs of efficacy in anxiety disorders in humans.14 Microdeletions in the FAAH gene can cause elevated endocannabinoid concentrations and a lifelong absence of pain, anxiety and depression.15 Plant-derived cannabinoids (phytocannabinoids) such as Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) preferentially modulate the ECS, and this provides a rationale for their use in treating anxiety.

Phytocannabinoids

Cannabinoids can be broadly grouped into endocannabinoids, synthetic cannabinoids and phytocannabinoids. Phytocannabinoids are the most commonly studied cannabinoids for therapeutic applications: more than 140 have been identified in Cannabis sativa, with the most prevalent being THC and CBD.16 THC and synthetic cannabinoid analogues of THC (eg nabilone) act as CB1 receptor agonists, with this pharmacological action responsible for the intoxicating effects of cannabis (ie being ‘stoned’).

CBD, in contrast to THC, is not an agonist at CB1 receptors and does not intoxicate. CBD has a broad pharmacological profile that includes elevation of endocannabinoid concentrations (via enzymatic and transporter inhibition), agonist activity at the 5-HT1A receptor,17 and numerous actions at ion channels and G protein–coupled receptors. Anxiolytic effects of CBD in animal models are well described and have been linked to a pharmacological action at 5-HT1A receptors.18 Benzodiazepine-like effects of CBD at GABA receptors have also been described.19

Efficacy of medicinal cannabis for anxiety

More than 220 medicinal cannabis products are currently available in Australia, mostly in the form of orally delivered liquids, sprays and capsules, although medical grade herbal cannabis (‘flos’ or ‘flower’), which is intended for vaporisation, is increasingly popular, accounting for more than 40% of current prescriptions.

8 In general, oral products can be THC-dominant, CBD-dominant or contain mixtures of THC and CBD at specific ratios. In some products, THC and/or CBD may be the only pharmacologically active ingredient present (often called ‘isolate’ products), while other products may contain THC and/or CBD alongside an ‘entourage’ of other cannabis plant components such as terpenes and minor phytocannabinoids (eg cannabidiolic acid, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid, cannabigerol, cannabichromene). Herbal cannabis products are almost invariably THC-dominant. Clinical trials of cannabinoids for anxiety disorders have tended to use orally delivered ‘isolate’ THC and/or CBD preparations. As summarised recently in several systematic reviews and meta-analyses,

20–25 the trial evidence to date is patchy, low quality and at high risk of bias.

THC and THC analogues

In a recent meta-analysis, Black et al concluded that THC produces marginally greater reductions in anxiety than placebo but noted that none of the seven studies included in their meta-analysis involved patients with a primary anxiety disorder.20 Rather, anxiety was a secondary outcome in studies in which the primary outcome was pain reduction. Nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid with high affinity at CB1 and CB2 receptors, reduced anxiety in two out of four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with chronic pain,26–29 while two studies involving dronabinol (synthetic THC in capsule form) for pain found no significant effect on anxiety.30,31 More information on medicinal cannabis in the treatment of pain can be found in the article by Henderson and colleagues in the October 2021 issue of Australian Journal of General Practice (AJGP).32

A recent review of the evidence supporting the use of THC, THC analogues or THC-dominant herbal cannabis in PTSD found emerging evidence for positive effects on sleep, nightmares and global PTSD symptoms; however, again, good-quality clinical trials were lacking.24

Cannabidiol

Recent meta-analyses note preliminary evidence for CBD in the treatment of social anxiety, substance use disorders, autism spectrum disorder and psychosis.21,22,25 Laboratory studies in healthy volunteers placed in anxiety-provoking situations (eg simulated public speaking) show the anxiolytic potential of CBD.17,33 In patients, three case reports and one case series suggest that CBD has efficacy in reducing anxiety severity in patients with anxiety disorders.34–37 CBD also significantly reduced anxiety evoked by a public speaking paradigm in patients with social anxiety disorder.38 One small RCT investigated the impact of a four-week intervention of 300 mg CBD per day on anxiety severity in young adults with social anxiety disorders (n = 37).39 In this trial, anxiety decreased by 12.1 points on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale in the CBD group, compared with 3.1 points in the placebo group.

The current authors have recently concluded an open-label 12-week trial of CBD at escalating doses between 200 mg and 800 mg per day in young people with anxiety disorders (n = 31) who had previously not responded to standard treatment. Anxiety severity was significantly improved after the 12-week intervention with adjunctive CBD.40 Twelve of 30 (40%) participants had a reduction of at least 50% in Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS) scores by week 12, and 18 of 30 participants had a reduction of at least 33%. Twenty-six (86.7%) of 30 participants showed significant clinical global improvement at Week 12. Other clinical trials of CBD for anxiety disorders are ongoing.41,42

An observational study surveyed the first 400 New Zealand patients to receive CBD on prescription (most were prescribed 100 mg CBD/mL in oil administered by dropper).43 Dosing varied from 40 mg to 300 mg/CBD/day. Results showed that median anxiety and depression ratings decreased from 4 (severe problems) to 2 (slight problems) on the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 5 Level Version (EQ-5D-5L) at follow-up in patients with a primary mental health diagnosis. Similarly, improvements in anxiety and depression were noted in patients being treated with CBD for chronic pain or neurological conditions. Taken together, these results suggest some promise for CBD in the treatment of anxiety, but larger RCTs are clearly required.

Safety, adverse effects and drug interactions

Prescribers and health practitioners working with patients who are consuming medicinal cannabis products should be aware of the limitations and unwanted side effects associated with medicinal cannabis products and discuss these risks with their patients. The side effects of THC are well described and include nausea, dizziness, increased appetite, euphoria and the potential for dependence (Table 1).44 At higher doses, THC can have sedative effects and may cause heightened or altered sensory perception and depersonalisation. THC can exacerbate anxiety in vulnerable individuals,45,46 particularly in inexperienced users given relatively high doses. Doses of 20–30 mg THC per day seem particularly prone to elicit psychotomimetic and other adverse effects.47

| Table 1. Adverse events of cannabidiol (CBD) and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) observed in clinical trials |

| CBD |

THC |

- Diarrhoea

- Increased or decreased appetite*

- Mild sedation*

- Seizures*

- Pneumonia*

- Inhibition of CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4

|

- Euphoria

- Increased appetite

- Nausea

- Dizziness

- Sedation

- Drug dependence

- Altered sensory perception

- Depersonalisation

- Anxiety

|

| *Statistically significant only in trials of patients with epilepsy concurrently taking anti-epileptic medication |

These potential side effects should be openly discussed with patients and doses of medicinal cannabis products titrated gradually upwards, particularly in cannabis-naive patients. It is also important to remind patients that a valid prescription for a THC-containing product does not currently provide an exemption against Australian drug-driving laws, which state that the mere presence of THC in oral fluid or blood of drivers is illegal. Issues regarding medicinal cannabis and driving have been reviewed in AJGP in an article by Arkell and colleagues.48

CBD is generally non-intoxicating and well tolerated in doses up to 1500 mg per day in clinical studies.49 At the time of writing, there are no restrictions relating to CBD and driving in Australia: recent evidence suggests that CBD does not impair driving.50 In a recent meta-analysis of 12 randomised clinical trials of patients treated with CBD (n = 803 patients),51 adverse events that were more common in patients taking CBD than in those taking placebo included mild sedation, diarrhoea, increased or decreased appetite, abnormal liver function tests, pneumonia and seizures. Of note, when clinical trials of patients with epilepsies were excluded, the only adverse event that occurred significantly more often in the CBD group was diarrhoea. Transient elevations of liver enzymes were reported in one study of patients treated with CBD.52 While clinical trials show that CBD appears to be well tolerated in most patients, data regarding the long-term safety of CBD are currently limited to studies of paediatric epilepsy patients.53 The safety of CBD during pregnancy remains uncertain.54

CBD is a known inhibitor of cytochrome P450 enzymes, including CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4.55 Many commonly prescribed anxiolytics and anticonvulsants, and some antidepressants, are substrates for these enzymes. Accordingly, CBD has the potential to increase plasma concentrations and side effects of medications that are metabolised by these enzymes. For example, CBD can increase plasma concentrations of anticonvulsant medications such as clobazam and topiramate, leading to exaggerated anticonvulsant side effects (eg somnolence) in some patients.56 Interactions with benzodiazepines and antidepressants, widely used in the treatment of anxiety, are conceivable and require further exploration. A recent study by the current authors showed elevated plasma concentrations of citalopram and escitalopram in patients treated concomitantly with CBD.57 Given this potential for drug–drug interactions, careful upwards titration of CBD in CBD-naive patients is recommended.5

Prescribing uncertainties

SAS-B prescribing data show that the TGA provided 58,782 approvals for the prescription of medicinal cannabis products for ‘anxiety’ from November 2016 until June 2022.6 Approvals for anxiety and PTSD are now accumulating at more than 4000 per month (Figure 1). Approximately 17% of current approvals are for Schedule 4 products in which, by definition, CBD accounts for more than 98% of the total cannabinoid content (Figure 1). These CBD products are predominantly oils, but they also include capsules and wafers. The remaining prescriptions are for Schedule 8 products, which are either THC isolate products or mixed THC/CBD products. Strikingly, the TGA dashboard tool shows that approximately 50% of TGA approvals for anxiety in May 2022 were for Schedule 8 THC-containing herbal cannabis products intended for vaporisation.6 The number of approvals specifically for PTSD is less than 10% of that for anxiety, and approvals are dominated by THC-containing products, particularly herbal cannabis (Figure 1). This is in line with emergent evidence of the benefits of THC for insomnia and other PTSD-related symptoms.24

Figure 1. Data obtained from the Therapeutic Goods Administration dashboard tool

(www.tga.gov.au/medicinal-cannabis-special-access-scheme-category-b-data) showing total Special Access Scheme Category B (SAS-B) approvals for the month of May 2022 for Schedule 4 (S4) and Schedule 8 (S8) medicinal cannabis products by conditions treated. Anxiety is second only to chronic pain as the most common condition being treated, with approximately 17% of anxiety-related approvals for cannabidiol-dominant (S4) products (n = 642) and the remainder for S8 products (n = 3142) that contain Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol.

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder

There is some evidence that the addition of CBD to a THC-containing product may minimise some of the intoxicating and other adverse psychological effects of THC (eg paranoia, anxiety), although this remains controversial.50,58,59

In Australia, medicinal cannabis products are unregistered drugs and therefore require approval under the TGA SAS-B or Authorised Prescriber Scheme. Details of the application process, including instructional videos, can be found on the TGA website.6 There is little current guidance regarding when medicinal cannabis products might be considered appropriate for the treatment of anxiety and whether they can be safely combined with prescription medications such as benzodiazepines, antidepressants and antipsychotics. Perhaps surprisingly, Australian doctors rate medicinal cannabis products as somewhat less hazardous than these conventional psychotropic medications,60 while evidence from the USA suggests that the use of medicinal cannabis is sometimes associated with decreased use of benzodiazepines, antidepressants and opioids.61,62 Co-prescription of CBD or THC with these conventional psychotropic medications should be undertaken with some caution given the potential for drug–drug interactions with CBD and possible potentiation of sedation and impairment with THC.

Likewise, appropriate dosing of medicinal cannabis products remains uncertain. Clinical trials reporting reductions in anxiety severity after administration of CBD used doses between 300 mg and 800 mg of CBD per day. However, the reality in clinical practice is that many patients cannot afford such doses. Medicinal cannabis products do not currently attract subsidy under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), and with CBD currently costing approximately 10 cents/mg, it is easily seen that 800 mg/day doses may be unaffordable for many patients. Consequently, it appears more typical for Australian and New Zealand doctors to prescribe CBD at approximately 50–300 mg day, although the efficacy of such doses remains uncertain.43,63

The TGA has announced (December 2020) the down-scheduling of low-dose CBD products to Schedule 3 (Pharmacist Only Medicine), meaning that products involving daily CBD doses of 150 mg or less are available over the counter (OTC) in pharmacies. While current clinical trial evidence provides little validation of the efficacy of this dose range,64 it is likely that patients will be attracted to trialling these products and an increasing number of patients self-medicating with CBD products will be attending medical consultations.

Conclusion

Anxiety disorders are the second most common reason for the prescription of medicinal cannabis products in Australia and a major driver for self-medication with illicit cannabis. The limited evidence to date suggests that CBD has anxiolytic properties in doses between 300 mg and 800 mg per day and may be effective in patients for whom existing treatments have proved inadequate. Studies of lower-dose CBD products in clinical populations are clearly required, given that such products will soon become available OTC and are likely to prove popular. The side effects of CBD observed in clinical trials to date provide little major cause for concern, although prescribers should remain vigilant for possible drug–drug interactions. While THC products, including large amounts of herbal cannabis, are being widely prescribed in Australia for anxiety disorders and for PTSD, there is currently little evidence to support this intervention. Clinical use of THC must proceed cautiously because of its tendency to induce anxiety in some patients at higher doses and because of current driving restrictions. Prescribers should openly discuss the risks and potential benefits with their patients and remain updated in this dynamic and rapidly evolving area of clinical practice.

Key points

- Anxiety is the second most common condition for which medicinal cannabis is prescribed in Australia.

- Most medicinal cannabis products are unregistered drugs, and prescribing requires approval under the TGA SAS-B or Authorised Prescriber Scheme.

- CBD, a non-intoxicating cannabinoid found in Cannabis sativa, reduced anxiety severity in doses of 300–800 mg per day in several small trials. Larger trials, however, are lacking, as are good-quality studies at lower CBD dose ranges.

- There is less evidence to support the use of THC-dominant formulations for anxiety disorders, although there is some emerging evidence for PTSD. THC can exacerbate anxiety under some conditions, and patients taking THC-dominant formulations are restricted in their ability to drive.