Minimally disruptive medicine (MDM) is a ‘a patient-centred approach to care that focuses on achieving patients’ goals for life and health while imposing the smallest possible treatment burden on their lives’.1 The term appeared in the medical literature for the first time in 2009 in an analysis of the rise of complex and chronic comorbidities worldwide.2 The authors of that initial paper highlighted that the healthcare response to the growing burden of complex and chronic comorbidity has mainly been to develop an increasing number of treatments, guidelines and recommendations, creating a growing burden for patients. Health professionals should consider whether what is ‘done to’ or ‘asked of’ patients with complex chronic morbidities is achieving their goals for life and health or those of the health system.

Complex multimorbidity in Australian general practice

The term ‘complex multimorbidity’ has been defined as the ‘co-occurrence of three or more chronic conditions affecting three or more body systems within one person, without defining an index condition’.3 It is estimated that approximately 22% of the Australian population would fall within this definition, with the most common combination of chronic conditions being circulatory, musculoskeletal and nutritional/metabolic/endocrine.3

Australia’s population is ageing, with the latest Census showing an increase in population aged >65 years to 15.3% and over 2% aged >85 years.4 The latter almost always have complex chronic multimorbidity, with 60% having high morbidity profiles that result in high rates of polypharmacy, overnight hospital admissions and general practitioner (GP) visits.5 Greater cognitive impairment is also associated with increased multimorbidity. Over 70% of patients with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment have a high level of complex comorbidity.6 Australian GPs are likely to see more patients fitting these profiles over the coming years and need meaningful ways to practice MDM with them.

Burden of treatment and capacity to handle the workload of healthcare

MDM explicitly acknowledges that guidelines and protocols may need to be adjusted to take into account patients' preferences, context and circumstances when the burden of treatment is assessed.1 Being a patient can be ‘hard work’ and this should be acknowledged in the healthcare provided. This is particularly the case for patients with multimorbidity. Responses from 2500 Australians aged >50 years in a recent study estimated that patients with three or more chronic conditions spent between 37.5 and 44.0 hours per month on health-related activities.7 Those with five or more chronic conditions reported that they spent between 71.5 hours and 109.5 hours per month on health-related activity – that is, between 2.5 and 3.5 hours per day on average.7

However, time spent on healthcare is only one aspect of treatment burden to assess and consider. A video analysis of 46 consultations with diabetics in the US found that burden of treatment issues were mentioned 83 times in these 46 consultations, but burden of treatment concerns were addressed only 30% of the time. These burden of treatment issues fell into four broad groupings:8

- Access – patients’ efforts or difficulty obtaining treatment in a timely, convenient or affordable manner

- Administration – burdens in correctly delivering or taking treatment

- Effects – unwanted or unintended symptoms or consequences of the prescribed treatment

- Monitoring – trouble complying with the monitoring required for effective or safe use of medication and following its ongoing effects.

The burden of treatment issues most frequently raised were in the ‘Administration’ domain (34%), followed by ‘Effects’ (29%), ‘Access’ (23%) and ‘Monitoring’ (14%). Patients were most likely to raise ‘Administration’ burden issues (20 out of 28 mentions), but ‘Administration’ burden was the least likely to be addressed in the consultation (only on two out of 28 mentions).8 Providers, on the other hand, were more likely to raise ‘Access’ issues (11 out of 19 mentions) and these were addressed more frequently (9 out of 19 mentions). Although this is a relatively small study from 11 primary care clinics affiliated with the Mayo Clinic in the US, and may not be fully generalisable to the Australian general practice context, it prompts consideration of who sets the agenda for chronic disease management and whether GPs are listening to their patients. It is important to note also that this study only analysed consultations in diabetic patients making treatment decisions about anti-hyperglycaemic treatment who were not necessarily experiencing multimorbidity. It is likely that burden of treatment issues would be even more common in such patients.

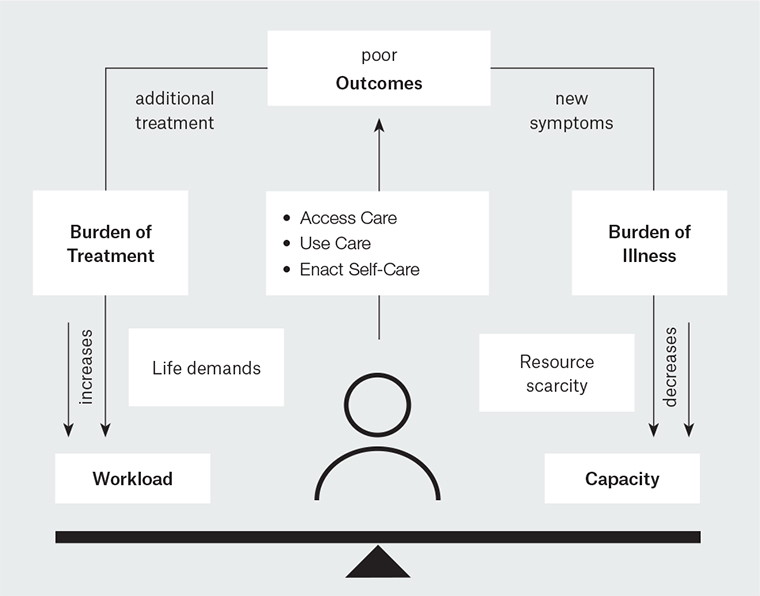

MDM is based on the cumulative complexity model (CCM; Figure 1).9 It acknowledges that in complex patients, the workload of healthcare is often moderated by the capacity to handle the work.9 Complex multimorbidity is more common in those who have less capacity due to advancing age, cognitive decline and lower socioeconomic status. Capacity can be influenced by a range of factors including cognitive, physical and financial resources, emotional wellbeing, fatigue, resilience, educational level, cultural background, age, gender and employment conditions, social support and healthcare structures.10–12 In the same way that burden of treatment and workload should be assessed, so too patients’ capacities should be considered. The aim of MDM is to reduce the workload and increase the capacity for patients with complex and multiple chronic conditions.13

Increasing patients’ capacity to cope with complex multimorbidity is more than just accessing and mobilising resources. It involves helping people to reframe their lives, enhancing social function, mobilising resources, realising which tasks are necessary, finding ways to integrate healthcare workload into normal daily life and creating a kind, empathic and feasible treatment plan.12

Figure 1. The cumulative complexity model

Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature, from Serrano V, Spencer-Bonilla G, Boehmer KR, et al. Minimally disruptive medicine for patients with diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2017;17(11).

Measuring burden of treatment in patients with complex comorbidity

Assessing the burden of treatment in patients with complex and chronic conditions needs to go beyond considering the ‘workload’ of healthcare; it must also assess the impact of this workload on the functioning and wellbeing of patients.14 A systematic review of treatment burden measures for individual chronic diseases found 57 patient-reported outcome measures across the chronic conditions of diabetes, kidney disease and heart failure.15 The authors identified 12 content domains that were common across all 57 patient-reported measures. Further development of this work went on to define a framework for the burden of treatment in patients who had multiple chronic conditions (Table 1).14,16,17 Although most of this work derived initially from the experiences of patients in the US, further testing in over 1000 patients across 34 countries in English, French and Spanish has confirmed that the three key domains of burden of treatment hold true in other settings.17

This framework for measuring burden of treatment is potentially useful for GPs in clinical practice, but it would require adaptation and feasibility testing. For example, it could be adapted for use in care planning and coordination, even if this only includes the three column headings in Table 1. GPs could therefore, at a minimum, consider:

- What are the healthcare tasks being imposed on this patient?

- What factors (eg personal, social, financial) could exacerbate the burden of treatment in this patient?

- What are the consequences of the healthcare tasks imposed on this patient?

| Table 1. A measurement framework for burden of treatment in complex patient with multimorbidity17 |

| Healthcare tasks imposed on patients |

Factors that exacerbate

the burden of treatment |

Consequences of healthcare tasks imposed |

1. Managing medication

- Prepare and take medicines

- Plan and organise medicine intake

- Follow specific precautions before, during or after intake

- Store medicines at home

- Refill medicine stock

2. Organising and performing non-pharmacological treatments

- Access/use equipment

- Plan/perform physical therapy

3. Lifestyle changes

- Force self to eat certain foods

- Eliminate some foods

- Plan and prepare meals

- Be careful of ingredients in meals

- Organise physical exercise

- Perform some physical activities

- Give up some physical activities

- Change/organise sleep schedule

- Give up smoking

- Perform other lifestyle changes

4. Condition and treatment follow-up

- Plan and organise self-monitoring

- Plan and organise lab tests

- Precautions before/when performing tests

- Plan and organise doctor’s visits

- Remember questions to ask doctor

- Organise transportation

5. Organising formal caregiver care

6. Paperwork tasks

- Take care of administrative paperwork

- Organise medical paperwork

7. Learning about and developing an understanding of the illness and treatment

- Learn about the condition and treatment

- Navigate the health system

|

1. Nature, time required and frequency of healthcare task

2. Structural factors

- Access to resources

- Medicine out of stock

- Access to lab results

- Access to right health provider

- Distance to health facilities

- Difficulty planning last-minute consultations

- Lack of coordination between health providers

- Health facility problems (wait times, parking etc)

- Not enough research done on particular health condition

- Insufficient or inadequate media coverage of the health condition

3. Personal factors

- Beliefs

- Anxious about tests and results

- Believe some consultations useless

- Believe some follow-up tasks useless

- Believe treatment inefficient

- Feel dependent on treatment

- Treatment conflicts with religious beliefs

- Relationships with others (except healthcare)

- Feels a burden to others

- Loved ones impose too many precautions

- Loved ones don’t help with healthcare

- Hides condition/treatment from others

- Has to regularly explain condition to others

- Seeing other patients triggers fears for the future

- Relationship with healthcare providers

- Physicians don’t know about condition/treatment

- Physician doesn’t take patient context into account

- Healthcare providers don’t explain things

- Feel providers don’t believe what is said

- Providers don’t consider psychological problems

- Providers neglect some problems for others

- Feels treated like just a condition, not a person

4. Situational factors

- Out of routine

- Plan and organise travel

- Store medications when not at home

- Take medications when not at home

- Access to structures or equipment when not at home

- Pregnancy

- Other situational factors

- Changing physicians

- Organise diet to accommodate other people

- Follow diet in the presence of other people

5. Financial factors |

1. Lack of adherence

- Intentional non-adherence due to complexity

- Intentional non-adherence due to costs

- Non-intentional non-adherence and strategies not to forget treatment

2. Impact on professional, social, family life and leisure activities

- Opportunity cost to professional life

- Coping with absence from work

- Healthcare activities interfere with career (eg lack of promotion)

- Coping with judgement from others

- Treatment takes time/energy that interferes with family/friend commitments

- Healthcare activities interfere with life as a couple

- Treatment takes time/energy or requires precautions that interfere with leisure activities

3. Emotional impact

- Frustration of not being able to do everything wanted

- Guilt associated with intentional non-adherence to treatment

- Treatment is a reminder of chronic conditions

4. Financial impact

- Direct costs of treatment

- Indirect costs of treatment

|

Implementation in clinical practice

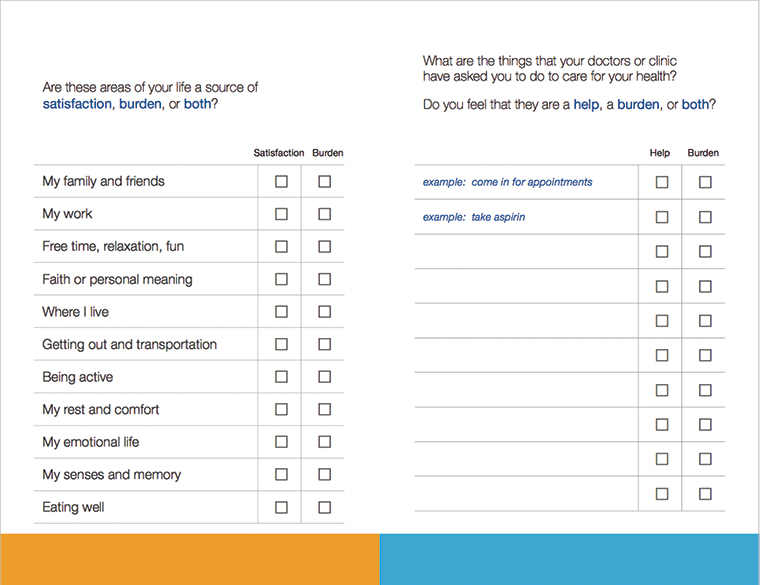

One way of implementing MDM in clinical practice is to use the principles of shared decision-making. This allows clinicians and patients to co-create a feasible and reasonable treatment plan together. The videographic analysis study cited earlier in this article was a sub-study of a randomised controlled trial of a patient decision aid that showed use of the aid resulted in greater discussion of burden of treatment issues.8 The Instrument for Patient Capacity Assessment (ICAN) discussion aid was designed to help clinicians and patients assess the burden of treatment and patients’ capacity within the clinical encounter (Figure 2).18 The clinician component suggests three questions that could be helpful in shifting discussions towards the broader life of the patient and to identify workload and capacity issues. The questions are:

- What are you doing when you’re not sitting here with me?

- Where do you find the most joy in your life?

- What’s on your mind today?

The ICAN discussion aid also has a simple patient checklist that aims to assess workload, capacity and impact. It asks patients to list the things that their doctors or clinic have asked them to do to care for their health, and whether they find these a ‘help’, a ‘burden’, or both. It also asks about areas of life that are a source of satisfaction, a burden, or both. These include family and friends, work, free time/fun/relaxation, faith or personal meaning, place of residence, getting out and transportation, being active, rest and comfort, emotions, senses and memory, and eating well. Both components of the ICAN discussion aid can be downloaded free of charge at minimallydisruptivemedicine.org

Figure 2. ICAN patient card discussion aid

© 2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Research and Education. Used with Permission.

Implications for Australian general practice

MDM has immediate relevance to care planning and coordination with patients who have complex and chronic multimorbidities in Australian general practice. The ICAN discussion aid is available online and can be used freely with patients at any time. The principles of MDM align perfectly with those of holistic and patient-centred care, which are underpinning principles for good-quality general practice. However, it should be ensured that GPs and their patients are not penalised for making deliberate, well-informed and compassionate care plans that take into account treatment burden and the capacity of patients and carers to bear that load. Documenting the personal, social and financial burden of treatment could potentially drive more equitable healthcare and reduce unnecessary testing and treatment in vulnerable patients. However, policies need to enable this approach, and further debate on this topic would be welcome. As Australia implements the Health Care Homes policy, care must be taken not to increase the number of overwhelmed patients with complex comorbidity. If payment incentives are tied to a checklist of health-related activities that patients must complete, there is a risk making things worse, not better, for everyone. In the UK, suggestion has been made that consideration of the burden of treatment should be a quality indicator and, at a minimum, patients should be asked, ‘Can you really do what I’m asking you to do?’19 The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline for multimorbidity explicitly recommends the establishment of disease and treatment burden alongside patient goals, values and priorities.20 Australia urgently needs a similar guideline. Little is known about how the Health Care Homes policy will evolve in Australia despite a tranche of practices already enrolling patients for the first trial, which will end in December 2019. Much of the focus appears to be on care plans and coordination, with no mention of treatment burden or patient capacity. Given the international body of work outlined in this paper, this is deeply concerning.

The Health Care Homes policy should include and recommend the principles of MDM for complex multimorbid patients. The management of multimorbidity in Australian general practice would then include reducing the treatment workload for patients with complex comorbidity. It would prioritise and simplify treatment regimens rather than requiring patients and carers to ‘do it all’. De-prescribing of burdensome and unnecessary medications, simplifying paperwork and bureaucracy, reducing the number of doses of medication and clinic visits, and considering the hidden costs of healthcare such as transportation and time off work for family members and carers, are all possibilities if the policy supports and endorses this approach. MDM in Australian general practice would also consider patients’ capacity to cope with the workload of complex multimorbidity. The holistic philosophy of general practice is ideally suited to discussing social support and quality of life. However, current health practice is constrained through lack of funding for community-based social work, adequate community-based health literacy programs, and limited support for patients from culturally diverse backgrounds. Coordination and care plans are good and necessary, but they should also allow kindness, empathy and be feasible for the most vulnerable.