Approximately 49% of women will be affected by hair loss throughout their lives, with female pattern hair loss (FPHL) being the most common cause of female alopecia.1 The incidence steadily increases with age in all ethnicities, and the age-adjusted prevalence among adult Australian women of European descent is >32%.1–4 This translates to 800,000 women who suffer from moderate-to-severe FPHL.4 Alopecia is associated with significant psychological distress and reduced quality of life. In one survey, 40% of women experienced marital problems and 64% had career difficulties that they ascribed to their hair loss.5 Alopecia can also be the first symptom of underlying systemic illness within the primary care setting.1,6

FPHL is a non-scarring alopecia characterised by progressive transformation of thick, pigmented terminal hair into short, thin, non-pigmented villous hair. This undesired process is known as hair follicle miniaturisation.1,3,5,6 The trigger for miniaturisation remains unclear but is postulated to be a combination of genetic predisposition, androgen influence and other not yet elucidated factors. Androgens exert their effect on hair via circulating levels of testosterone, which is produced in females by the ovaries and adrenal glands. The free testosterone either binds to intracellular androgen receptors in the hair bulb, causing follicular miniaturisation, or is metabolised by enzyme 5-alpha reductase into dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT and testosterone both bind to the same androgen receptors, but DHT does so with more affinity, leading to increased miniaturisation.3,5,6

Female pattern hair loss and general health

As alopecia is highly visible, a patient may note hair loss as the first symptom of a host of underlying or contributing medical and psychiatric conditions. All causes of hyperandrogenism, such as ovarian or adrenal tumours, polycystic ovarian syndrome and adrenal hyperplasia, can induce rapid hair loss in women. The diagnosis of FPHL is associated with underlying hypertension in women aged £35 years and coronary artery disease in women aged £50 years.7 One study found that patterned hair loss was an independent predictor of mortality from diabetes mellitus and heart disease in both females and males.7–9 Screening for metabolic cardiovascular risk factors is useful in patients presenting with patterned hair loss.3,10

Risk factors

The risk factors for FPHL include increasing age, family history, smoking, elevated fasting glucose levels and ultraviolet light exposure of >16 hours/week.8

Psychological morbidity

FPHL is less well understood and accepted by society than alopecia in males. This generates feelings of greater confusion and distress for female patients. A study showed that 52% of women were very-to-extremely upset by their hair loss, compared with 28% of men.1 In another questionnaire, 70% of surveyed women with hair loss had a negative body image and poorer self-esteem, with poorer sleep, feelings of guilt and restriction of social activities.3 Clinicians should also screen for maladaptive coping mechanisms such as compulsive fixing of one’s hair and underlying psychiatric trichotillomania.1,10,11

Assessment

The diagnosis of FPHL is made on clinical grounds.4,5

History

Classically, the pattern of alopecia begins with hair density reduction on the mid‑frontal hairline. The anterior part width then widens, resulting in prominent thinning in a Christmas tree pattern (Figure 1) .

Figure 1. Female pattern hair loss with Christmas tree pattern

Generalised and rapid shedding with global hair thinning is unusual and points to other causes such as hyperadrenalism, medication exposure, major stressors or change in hair care practices.1,3,6,10,11 Hair loss over the temporal region is uncommon in FPHL, compared with male pattern alopecia. If temporal thinning was the first symptom, telogen effluvium, frontal fibrosing alopecia, tractional alopecia and hypothyroidism should be considered.6 Symptoms of scalp pruritus, burning and pain point to another diagnosis (Table 1).6

|

Table 1. Key features in history taking and examination for detection of underlying systemic illnesses1,6,10

|

|

Underlying systemic diseases that may present with alopecia

-

Virilising tumours

-

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

-

Hyperandrogenism +/– associated metabolic syndrome

-

Thyroid dysfunction

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

-

Dermatomyositis

-

Iron deficiency +/– anaemia

-

Caloric restriction: anorexia/bulimia

-

Psychiatric disorder: trichotillomania

-

Medication/toxin exposure or ingestion

-

Infection: syphilis

|

|

Red flags on history taking for underlying systemic illnesses

-

Generalised and rapid hair shedding

-

Lateral eyebrow hair loss/thinning

-

Menstrual irregularity, fertility difficulty

-

Severe acne

-

Marked hirsutism

-

Associated cutaneous eruption

-

New photosensitivity

-

Severe fatigue

-

Weight changes: gain or loss

-

Fevers or chills

-

Joint and muscle aches

-

Severe psychological stressors

|

|

Examination findings suggestive of underlying disorders

-

SLE: isolated parietal alopecia, scarring alopecia (violaceous papules, follicular erythema), associated cutaneous malar rash, arthralgia

-

Thyroid dysfunction: temporal region alopecia, lateral eyebrow hair-loss

-

Trichotillomania: broken hair shafts of variable length, diffuse and patchy hair loss

-

Endocrinopathy: acanthosis nigricans, hirsutism, truncal acne (especially nodulocystic), high body mass index

-

Nutritional deficiency: conjunctival pallor, glossitis, muscle wasting

|

After diagnosing FPHL, concurrent medical illnesses that exacerbate alopecia should be ruled out to improve overall outcome. These include iron deficiency, infection, thyroid dysfunction and nutritional deficiencies.3,11 Occupational history and exposure to, or ingestion of, toxic chemicals should be elicited.10

Gynaecological history

A detailed gynaecological history is necessary to rule out hyperandrogenism, polycystic ovarian syndrome or a virilising tumour as underlying diagnoses. History should include age of menarche; menstrual cycle details; whether menopause has occured and, if so, at which age; use of hormonal contraception; fertility concerns and any previous gynaecological surgery.1,3,5 A discussion of pregnancy plans is necessary as some treatments are teratogenic.1

Family history

Fifty-four per cent of patients have a first-degree male relative of age >30 years with alopecia, and 21% have a first‑degree female relative aged >30 years with FPHL. An Australian gene-wide study of Caucasian women suggested that aromatase gene CYP19A1 may contribute to FPHL.3

Examination

General observations for body habitus, acne, hirsutism and acanthosis nigricans should be made. Focused examination should identify the calibre of the hairs and the location of the affected areas. Findings consistent with FPHL include:

-

loss of terminal hair in the mid-frontal scalp

-

normal hair density in occiput regions and preserved frontal hairline1,6

-

miniaturised hairs: hair of various lengths and diameters in thinning areas3,6

-

widening of central part with diffuse reduction in hair density in a Christmas tree pattern1,11

-

normal-appearing scalp

-

negative hair pull test: hold a bundle of 60 hairs close to the scalp between the thumb, index and middle finger. The test is positive when more than three hairs can be pulled away.12

Non-classic symptoms and signs that suggest other types of alopecia are outlined in Tables 1 and 2.

|

Table 2. History and examination findings of common non-scarring and scarring alopecia disorders6,10,11

|

|

Non-scarring alopecia (common)

|

Typical history

|

Examination findings

|

Hair pull

|

|

Female/male pattern hair loss

|

Age: puberty or older

Onset: gradual

Commonly positive family history

|

No marked shedding

Hair thinning, wider midline part of the crown, no bare patches, occipital region spared

|

Negative (usually)

|

|

Telogen effluvium

|

Age: adults

Onset: abrupt – triggered by iron deficiency, thyroid dysfunction, general anaesthesia, childbirth and medications

|

Prominent shedding

Global hair thinning – evenly distributed throughout scalp

No bare patches

|

Positive (if worse on frontal than occipital)

|

|

Alopecia areata

|

Age: ≤20 years

Onset: abrupt

Personal or family autoimmune history

|

Prominent shedding

Well-defined bald patches –

can be isolated or multifocal

Rarely with diffuse hair thinning

(5% can have complete alopecia)

|

Positive

|

|

Tinea capitis

|

Age: children

Onset: gradual/abrupt

Animal contact history (pets, zoos)

|

Prominent shedding

Bare patches of scalp

Any area of scalp can be affected, isolated or multifocal – can have inflammation and scales

|

Positive (can have broken hairs)

|

|

Trichotillomania

|

Age: children/adolescents

Onset: gradual/abrupt

Sensation of tension that is only relieved by pulling hair

History of other psychiatric disorders

|

Minimal shedding

Fronto-temporal hair or frontal parietal areas affected

Irregularly shaped patches of reduced hair density with irregular borders

|

Negative

|

|

Other common non-scarring alopecia differentials:

Hypothyroidism, nutritional deficiencies, traction alopecia, anagen effluvium, infections (syphilis)

|

|

Scarring alopecia

|

Typical history

|

Examination findings

|

Hair pull

|

|

Lichen planopilaris

|

Age: adults

Onset: gradual

Scalp itch and burning

50% of patients also have lichen planus

|

Variable shedding

Bare patches and/or diffuse thinning

Begins in parietal scalp

Perifollicular erythema and scales

|

Positive

|

|

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus)

|

Age: young adults

Onset: gradual/acute

Scalp itch and pain

More prevalent in Caucasian women

Associated systemic lupus erythematosus 10%

|

Variable shedding

Parietal area with bare patches

Scaly papules, erythematous and violaceous discolouration of scales, follicular plugging and telangiectasia

|

Positive

|

|

Folliculitis decalvans

|

Age: young and middle-aged adults

Onset: gradual

Scalp pain and itch

Common in men

|

Variable shedding

Begins at the vertex with bald patches

Follicular papules, pustules and crusting

|

Positive

|

|

Other differentials for scarring alopecia:

Dermatomyositis, dissecting cellulitis, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia

|

Laboratory investigations

Laboratory testing should be considered in patients with diffuse alopecia, signs of androgen excess and early-onset FPHL. Recommended tests and rationale are outlined in Table 3. Note that testing of androgen levels needs to occur during the follicular phase, between the fourth and seventh days of the menstrual cycle, and oral contraceptives should be discontinued eight weeks prior to the test.1,3

|

Table 3. Laboratory tests in hair loss evaluation1,3,10,11

|

|

Patient characteristics

|

Underlying disorder

|

Investigation

|

|

Menstrual irregularity, dysmenorrhea, severe acne and marked hirsutism

|

(Endocrine screen)

Hyperandrogenism

Ovarian hyperandrogenism

Adrenal hyperandrogenism

|

Androgen index test

Prolactin level

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) and 17-hydroprogesterone (17-OH)

|

|

Obesity, hirsutism, menstrual irregularity, severe acne and confirmed female pattern hair loss

|

Associated metabolic syndrome

|

Fasting blood sugar level

Fasting lipid profile

Blood pressure monitoring

|

|

Marked temporal region thinning and lateral eyebrow loss

|

Thyroid dysfunction related hair loss

|

Thyroid function test, thyroid antibodies

|

|

Arthralgia/myalgia

|

Systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune disorders

|

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, rheumatoid factor, autoantibody tests

|

|

Rapid and diffuse hair shedding in a sexually active individual

|

Alopecia syphilitica

|

Non-treponemal and treponemal antigen testing

|

|

Lymphadenopathy

|

Tinea capitis

|

Scalp fungal scrapings for culture and microscopy

|

|

Rapid and diffuse hair shedding, low body mass index

|

Nutritional deficiency

|

Iron studies and full blood count

|

Treatment

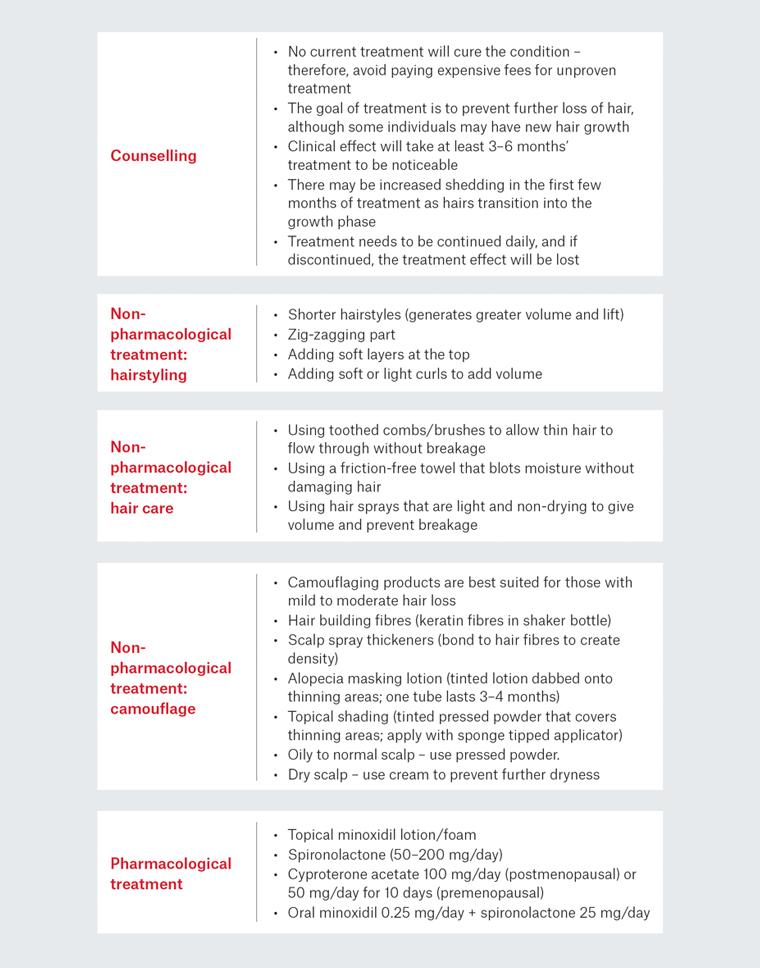

Key points of counselling and non-pharmacological treatment options are outlined in Figure 2. Pharmacological management is categorised into androgen-independent (non–androgen dependent) and androgen-dependent options.

Figure 2. Summary of counselling points and treatment options1,2,10,15

Non–androgen dependent treatments

Minoxidil is a piperidinopyrimidine derivative and a vasodilator that is used orally for hypertension. When applied topically, minoxidil is effective in arresting hair loss and producing some degree of regrowth.2

Topical minoxidil is the first-line therapy for FPHL, with Food and Drug Administration approval since 1992. It has been shown to stop hair loss and induce mild-to-moderate regrowth in 60% of women.2,13 It is available as a solution or foam in 2% and 5% concentrations, which show a 14% and 18% increase respectively in non-vellus hair after 48 weeks.2 Topical minoxidil has a well-established safety profile; local irritation and temple hypertrichosis are the main side effects.2,14 Treatment needs to be continued indefinitely. If treatment is stopped, clinical regression occurs within six months. The degree of alopecia will return to the level that would have occurred if there were no treatment.2

Oral minoxidil 0.25 mg daily in combination with spironolactone 25 mg was shown to be effective in reducing hair loss severity and hair shedding score at six months and 12 months in an Australian prospective study with 100 women with mild-to-moderate FPHL. Spironolactone was added to reduce the risk of fluid retention and augment treatment response.2 Side effects in the study were seen in eight patients: two had postural hypotension that was controlled with 50 mg sodium chloride; six patients had hypertrichosis that was managed with waxing. Two patients terminated oral minoxidil because of urticaria. There were no reports of hyperkalaemia or laboratory function abnormality.2

Androgen-dependent treatments

Androgen receptor blockers target androgen conversion and subsequent binding onto hair follicle target receptors in alopecia. Spironolactone and cyproterone acetate are most commonly prescribed as they have been shown to produce regrowth in 44% of patients.4

Spironolactone is an aldosterone antagonist and is used as a potassium-sparing diuretic. In alopecia, it acts by reducing the levels of total testosterone and completely blocking androgen receptor activity in target tissues. It is approved in Australia for the treatment of female hirsutism. It has been used off-label for FPHL with a treatment regimen of 50–200 mg daily for at least six months and shown to arrest progression in 90% of women and improve hair density in 30%.2 Common side effects are lethargy and menorrhagia, which improve after three months. This is a pregnancy category D medication.5,14

Cyproterone acetate directly blocks androgen receptor activity and decreases testosterone levels by suppressing luteinising hormone and follicle stimulating hormone release. Effective dosages are 100 mg daily in postmenopausal women, and 50 mg for 10 days in premenopausal women for three months.4 In one study of 80 patients, cyproterone produced similar results to 200 mg daily of spironolactone.5 This is a pregnancy category X medication as it may cause feminisation of the male fetus.14 Side effects include weight gain, breast tenderness and decreased libido.5

5-Alpha reductase inhibitors

Although 5-alpha reductase inhibitors have revolutionised the treatment of male pattern alopecia, their use in FPHL is limited because of lack of efficacy and the teratogenic potential (pregnancy category X).5 A finasteride dose of 1 mg daily was no better than placebo in treating FPHL in postmenopausal women and was only mildly efficacious in premenopausal women who had associated hyperandrogenism.14,15

Conclusion

FPHL is a common, non-scarring alopecia that affects women of all ages and carries significant psychological morbidity. It may be the first presenting complaint of hyperandrogenism, thyroid dysfunction or chronic deficient diet. A detailed history with appropriate laboratory testing to screen for associated cardiovascular disease, hypertension and metabolic syndrome is indicated. Sufficient time should be dedicated to discussing psychological adaptation, treatment options and realistic treatment goals. The introduction of low-dose oral minoxidil is the key recent advancement in the management of this challenging condition.