Multimorbidity: The scale of the problem

The prevalence of multimorbidity is on the rise,1,2 and it has become apparent that management of multimorbidity is among the most significant challenges faced by primary care clinicians today.3 Patients with multimorbidity have been shown to have a poorer health-related quality of life4 and poorer functional status,5 and multimorbidity is associated with an increase in healthcare use across both primary and secondary care settings.6 It has been shown in the UK that 78% of primary care consultations were with patients with multimorbidity.7 In Australia, 47.4% of general practice consultations were with patients with multiple conditions, and 27.4% of general practice consultations were with patients with ‘complex multimorbidity’.8

Managing patients with multiple morbidities is a difficult task. The guidelines set up to advise clinicians in clinical decision making are often focused on single diseases; these guidelines, when applied to patients with multiple chronic conditions, can lead to contradictory advice.9 Polypharmacy is frequently seen in patients with multimorbidity and has been considered to be a consequence of applying multiple disease-specific guidelines for this patient group.10 The risk of adverse drug events is also increased in patients with multimorbidity,11 and all of these factors contribute to the increased challenge of clinical decision making in this patient group.

Why is shared decision making important?

It has been suggested that individualised care, in which each patient’s case is considered on a holistic and personal basis, is important in tackling this complexity.12 Involving patients in the clinical decision-making process is integral to providing individualised care and is promoted as a hallmark of good clinical practice.13,14 It is also important from an ethical perspective for patients’ autonomy to be respected and for patients to be informed of the benefits and risks of decisions relating to their healthcare.15,16 This is especially important in the context of multimorbidity, when the benefits and risks may be less clear-cut and more complicated by the interplay of different chronic health conditions and treatment regimens. Eliciting the patient's health outcome priorities and preferences is key to this process of shared decision making. It can help to provide clarity for both the clinician and the patient in navigating through this decision-making process and potentially reduce the treatment burden by focusing on the patient’s priorities.

Challenges to shared decision making in multimorbidity

It has been shown previously that doctors find it difficult to incorporate the process of eliciting the patient’s priorities into their consultations and sometimes omit doing so altogether.17,18 The time constraints of general practice appointments may be one factor responsible for this omission. Patients may also find it difficult to express their feelings, given the constraints of a consultation, and may require time to consider what their priorities and preferences are. It has been suggested that doctors are at risk of making a ‘preference misdiagnosis’,19 in which they make an incorrect assumption regarding the priorities and preferences of their patients. Indeed, it was shown that doctors significantly overestimated the extent to which patients with breast cancer prioritised retaining their breast.20 Another study showed that doctors significantly overestimated the extent to which older patients prioritised continuation of life in the context of advanced dementia resulting in severe cognitive decline.21

While these were small studies carried out in the context of specific diseases, few studies have investigated whether primary care clinicians could be making a ‘preference misdiagnosis’ in the context of multimorbidity. Investigating this is important, as evidence of a significant mismatch between doctors’ perceptions of their patients’ preferences and the actual preferences of their patients would highlight a possible barrier to the process of shared decision making. It is equally important to investigate whether the treatment priorities of primary care physicians differ from the treatment priorities of patients with multimorbidity, as this could help to shed some light on why ‘preference misdiagnoses’ may be occurring and highlight another possible barrier to the process of shared decision making. The need to reconcile the differences in order to arrive at a mutually agreeable management plan in consultations with patients with multimorbidity would also become apparent.

Facilitating shared decision making in multimorbidity

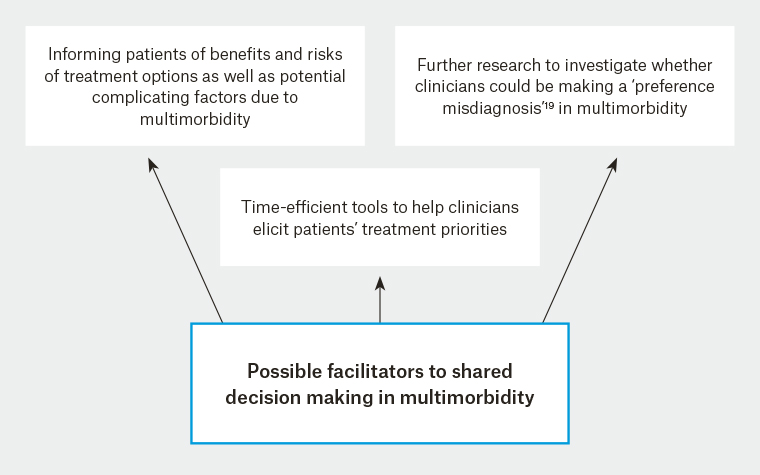

Finding ways to help primary care clinicians elicit the treatment priorities and preferences of their patients, within the time constraints of a primary care consultation, may be one way of facilitating the process of shared decision making (Figure 1). A tool for assessing the health outcome priorities of patients with multimorbidity has already been developed in the form of a short questionnaire.22

Figure 1. Possible facilitators to shared decision making in multimorbidity

Such questionnaires could be given to patients to complete either ahead of or during their consultations, so that primary care clinicians are aware of the health outcome priorities of their patients and can incorporate these priorities into the provision of individualised care. The priorities of patients may also change over time;

23 therefore, it would also be important to revisit this process periodically or at different clinical encounters. The challenge would be to develop a tool that is concise enough to be completed in a time-efficient fashion yet comprehensive enough to capture the patient’s views.