Case

A man from a semi-rural area, 36 years of age, presented to his general practitioner (GP) with a three-day history of a febrile illness and worsening headaches. His symptoms included fever, lethargy, headache and dry cough. The patient worked as a tradesperson and kept pet birds as a hobby. He had not travelled recently and no other household members were unwell. On examination, the patient had a temperature of 37.5

°C, heart rate of 145 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation of 96% on room air and scattered crepitations on auscultation. He had been previously well, was a current smoker, and did not have any other medical comorbidities.

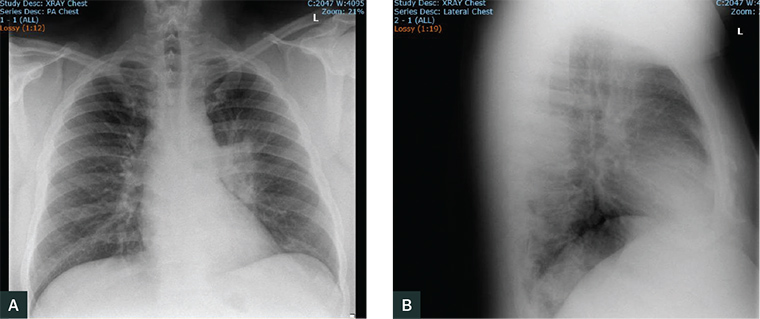

The GP diagnosed community-acquired pneumonia and prescribed oral amoxycillin with clavulanate. However, the patient’s condition continued to worsen over the next two days, with the development of worsening fevers, haemoptysis, myalgia, diarrhoea, night sweats and a maculopapular rash on his right arm. He was referred to the emergency department. On presentation, his white cell count was 13.3 x 109/L, neutrophil count was 10.1 x 109/L, and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 383 mg/L. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel for common respiratory pathogens was negative for influenza, picornavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza, human metapneumovirus and adenovirus. The patient’s chest radiograph is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The patient’s chest radiograph

Question 1

What does the patient’s chest X-ray show?

Question 2

What would you consider in your differential diagnosis? What are the important additional risk factors to elicit on clinical history?

Question 3

What tests are needed to confirm the diagnosis?

Answer 1

The patient’s chest X-ray shows peribronchial consolidation and a degree of collapse in the left perihilar area. This appearance is most suggestive of infection.

Answer 2

Although this clinical picture is typical of a severe community-acquired pneumonia, the patient’s poor response to empirical therapy, additional symptoms and presence of risk factors for zoonotic infection should prompt consideration of atypical pathogens and further investigation.

1 The history of bird contact raises suspicion of psittacosis (

Chlamydia psittaci infection). As common respiratory viruses were excluded, other differential diagnoses include

Chlamydia pneumoniae,

Mycoplasma pneumoniae and

Legionella infection. Had localising signs of pneumonia been absent, other diseases such as endocarditis, septicaemia, vasculitis,

Coxiella burnetii infection (Q fever), leptospirosis, brucellosis and arboviral diseases would also feature in the differential list. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion illness and non-infective causes should also be considered in the context of patient risk factors. Possible non-infective causes of this clinical presentation include vasculitides (eg systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyarteritis), hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and malignancy (eg primary lung or lymphoma).

Important considerations in the workup of this patient include occupational history (eg employment in agriculture, meat processing, veterinary industry), travel history and other risk factors for zoonotic disease (eg exposure to animal tissues or animal reproductive products, involvement in feral-pig hunting, mosquito or tick bites).

Answer 3

Diagnosis of atypical pneumonia can be difficult. With the exception of urinary antigen testing for Legionella infections, confirmatory diagnosis is often reliant on serology.2 In this setting, parallel testing for multiple pathogens is recommended.1 An atypical pneumonia serological panel will screen for Chlamydia, Legionella and Mycoplasma. If other zoonotic diseases are suspected, request paired serology for C. burnetii, Brucella and Leptospira species. While the utility of serology in acute illness management is limited by the unreliable nature of isolated acute-phase results, and treatment is likely to be completed before paired sera results are available, it can be useful in identifying exposure sources and tailoring future risk mitigation advice.2

Ideally, a diagnosis of psittacosis is confirmed through PCR testing on a throat swab or sputum sample. As not all laboratories have C. psittaci PCR testing capacity, specimens are often referred to a reference laboratory. Serological confirmation of the diagnosis requires collection of a convalescent serum specimen two to four weeks later. A fourfold or greater increase in C. psittaci antibody titre is considered confirmatory, while a single high antibody titre against C. psittaci is only suggestive of infection.3 Unfortunately, limitations of PCR and serology testing can lead to false negative results, and make laboratory confirmation of psittacosis challenging.

Case continued

The patient was diagnosed with severe pneumonia and commenced on benzylpenicillin, azithromycin, oseltamivir and prednisolone. His test results are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1. Patient’s serology results |

| |

12/09/16 |

02/9/16 |

Reference range |

| Chlamydia IgA (EIA) |

POSITIVE |

POSITIVE |

|

| Chlamydia IgG (EIA) |

POSITIVE |

POSITIVE |

|

| C. trachomatis IgG (MIF) |

256 |

128 |

<128 (titre) |

| C. pneumoniae IgG (MIF) |

256 |

256 |

<1024 (titre) |

| C. psittaci IgG (MIF) |

256 |

128 |

<128 (titre) |

| EIA, enzyme-linked immunoassay; IgA, immunoglobulin A; MIF, microimmunofluorescence test |

Question 4

How would you interpret these results?

Answer 4

In this case, antibodies for C. psittaci and C. trachomatis were raised. These results need to be interpreted in view of the clinical picture and exposure history, which are consistent with a diagnosis of psittacosis. The raised C. trachomatis antibody titre may be due to cross-reactivity, which occurs relatively commonly.4

Clinical manifestations of psittacosis usually begin five to 14 days after exposure, and are highly variable, ranging from mild illness to severe disease with multi-organ failure, although fortunately this is rare.5 Common symptoms include fever, headache, myalgia and non-productive cough, and diarrhoea may be present in around 25% of patients.6 Psittacosis may lead to neurological and cardiac complications and, in rare cases, death. Late-term pregnancy is a risk factor for severe disease.7 A careful exposure history can reveal direct or indirect contact with birds and help point towards the diagnosis.

Case continued

The patient was discharged home on amoxycillin with clavulanate. Five days later, the throat swab returned a positive C. psittaci result, and the patient was diagnosed with psittacosis. When interviewed by the public health unit, the patient gave a history of extensive hand feeding of wild native Australian birds and hand rearing of pet birds, including Indian ringnecks, lovebirds, budgerigars and lorikeets, with regular cleaning of the cages. He stated he had also recently purchased an incubator in which he was attempting to hatch duck eggs at home. The patient was recalled by the GP to review antibiotic management.

Question 5

What is the appropriate management of this condition?

Question 6

What strategies may prevent this condition?

Answer 5

Tetracyclines, such as doxycycline, are considered first-line treatment, and can be commenced empirically while waiting for a definitive test result.8 The duration of therapy is generally seven to 10 days, dependent on clinical response. Macrolides may also be considered for patients in whom tetracyclines are contraindicated. Psittacosis is a nationally notifiable condition to public health authorities. The local public health unit should be contacted to enable identification of any environmental sources of C. psittaci, such as pet shops or bird suppliers, that may pose an ongoing risk to the public.9,10

Answer 6

Psittacosis is a zoonotic disease transmitted through inhalation of infectious material ( eg bird faeces, cage litter). Direct contact with dead or sick birds is the principal route of exposure to C. psittaci; however, indirect contact through lawn mowing without a grass catcher and gardening have also been associated with transmission.11 Psittacosis is not currently vaccine-preventable. The correct use of personal protective equipment, including gloves and a correctly fitted P2 respirator, is strongly recommended when handling sick or dead birds and cleaning cages. In addition, general principles of infection control, including handwashing, cleaning workspaces and good ventilation are important to minimise exposure risk. Education should be targeted towards high-risk groups (eg bird fanciers, breeders or trappers), and the occupationally exposed (eg veterinary professionals, poultry processing workers, zoo workers, taxidermists).9,12

Key points

-

C. psittaci is a relatively rare zoonotic infection that can be transmitted from birds to people, and may result in a severe and potentially fatal pneumonia if unrecognised.

- The assessment of a patient presenting with a febrile illness should always include travel, occupational history and history of contact with animals, including birds.

-

Despite being an atypical cause of pneumonia, psittacosis is radiologically indistinguishable from other types of community-acquired pneumonia, and should be considered as a possible cause whenever there is a suggestive history of bird or animal contact.

-

Serology is unreliable for diagnosing psittacosis, and a respiratory specimen (throat swab) should be obtained and PCR testing requested if the diagnosis is suspected.