Inevitably, everybody dies, and indeed death is a universal health outcome. While most people say they would prefer to be cared for and to die at home, in the majority of cases this outcome is not achieved.1,2 The discrepancy between patients’ wishes and the realities represents a service gap that general practitioners (GPs) are optimally positioned to fill. The role of the GP assisting with palliative care will become increasingly important into the future. In 2015 about 160,000 people died in Australia,3 and this number is likely to double in the next 25 years.2 GPs may find palliative care time intensive, but with systematised management, palliative care is satisfying and efficient. This article presents three key clinical processes that GPs can systematise to effectively drive proactive care, and three elements essential to the delivery of high-quality palliative care.

Background

In Australia, only a small proportion of people die suddenly; most die from conditions with a predictable trajectory, experiencing a prolonged period of disability, frailty and illness and then dying at an older age ‘with unpredictable timing from a predictably fatal chronic disease’.4 In 2015, the five leading causes of death included coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer.5,6 If death is expected, it can be planned for. Estimates of the proportion of people who would benefit from palliative care vary from 50% to 90% of those who die, suggesting that 80,000–140,000 Australians would benefit from palliative care each year.7,8

Palliative care is multifaceted, team-based care that sits well within the GP specialist scope of practice. It is person-centred and family-centred care, provided to a person with active, progressive advanced disease(s) who is expected to die in the short term and for whom the primary treatment goal is to optimise quality of life.9 Demand for palliative care is increasing and has well surpassed a level that can appropriately be provided by hospital-based specialist palliative care services.10,11

GPs and home-based palliative care: The three key clinical processes

GPs have the sentinel role of managing community palliative patients, whether they are living in a private residence or a facility. In the UK, this role has been cemented into routine practice through the introduction of the Gold Standards Framework, which involves evaluation of palliative care needs in general practice.12 A simplified framework has been developed in Australia.13 There are three key clinical processes within those frameworks that can be easily systematised into practice to guide service delivery, using three essential palliative care elements.

1. Identifying patients at risk of deteriorating and dying (Case, part 1)

Probably the simplest, and surprisingly sensitive, clinical tool for this identification task is the surprise question: ‘Would you be surprised if the person died in the next twelve months?’14

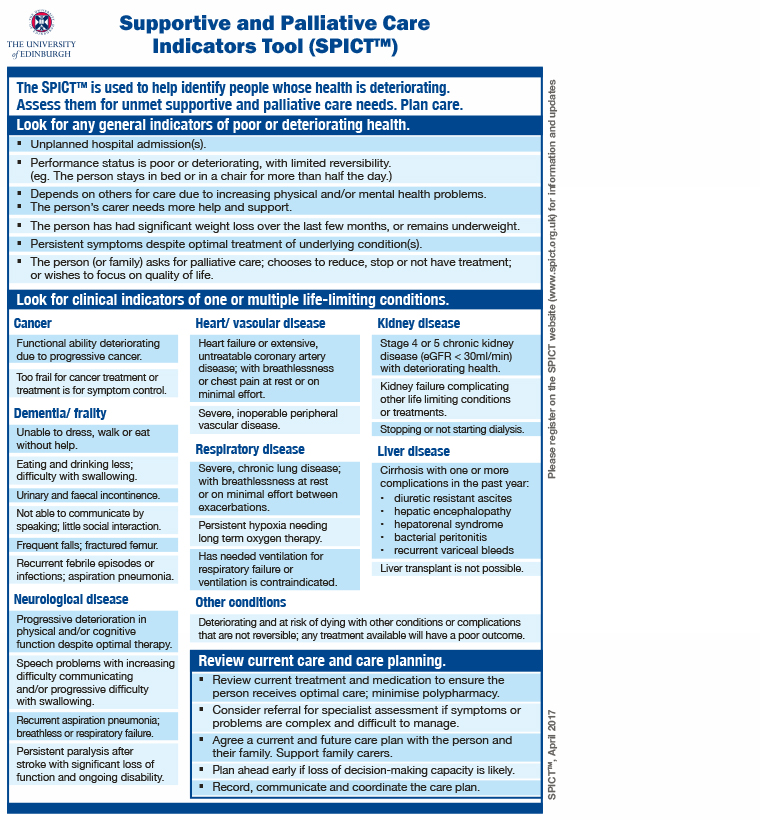

Another useful, though more structured, tool that helps identify people with general indicators of poor or deteriorating health and clinical signs of life-limiting conditions is the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicator Tool (SPICT).15 The SPICT (Figure 1) has gained international acceptance because systematic use encourages clinicians to organise well-coordinated supportive care integrated with appropriate treatment of the person’s underlying condition(s.

The surprise question and SPICT can be systematised into the Medicare Health Assessment for Older Persons (75+).

Identification of those at risk of death should trigger or re-instigate comprehensive discussions regarding the person’s goals and wishes for care, to inform a future management plan tailored to individual preferences. These iterative discussions are referred to as advance care planning, and discussion outcomes should be documented in a standardised way by the person or their substitute decision maker.16

Figure 1. Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT)

Figure 1. Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT)

Reproduced with permission from the SPICT International Programme

2. Formulation of a medical ‘goals of patient care plan’ (Case, part 2)

While an advance care plan is a patient communication tool, a ‘goals of patient care plan’ is a medical communication completed by the GP or other doctor. These plans inform other clinicians regarding appropriate responses when the person inevitably deteriorates.17,18 They are best completed when it is clinically timely to transition the focus of care from curative or restorative to palliative in intent.

Such a plan translates a person’s prior advance care plan into medical treatment orders.17 The plan identifies the patient’s goals of care and, importantly, matches those with specific medical escalations and limitations of active treatments (such as the provision or withholding of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, de-prescribing or transfer to hospital) proportionate to those goals.

The patient (if possible), their substitute decision maker(s) and other carers (paid and unpaid) should be made aware of the contents of the plan. The plan provides surety of actions in emotionally charged situations and so decreases uncertainty and distress.

3. Development of a terminal care management plan (Case, part 3)

When prognosis is limited to the last week or days of life, a shared documented terminal care management plan, focused on regular assessment of patient comfort and relief of carer/family distress,19 is advantageous. Medications to treat common emergent terminal symptoms usually need to be pre-emptively prescribed and charted for later administration by an appropriate route. Carers may need to be taught to manage breakthrough symptoms to avoid unnecessary suffering.

‘Death at home’ documents – such as standardised form letters stating the person is receiving palliative care or dying an expected death, and not for resuscitation measures but for all comfort cares – are valuable labour-saving resources. When available in the home, this documentation can ensure the person is not inappropriately resuscitated, transferred to hospital or referred to the coroner.

Proactively organising who will write the life extinct form and who will complete the death certificate can avoid after hours call-outs.

GPs and home-based palliative care: Three essential elements for high-quality palliative care

1. The compassionate GP

A compassionate GP empathises with palliative patients and acts to relieve suffering.20 Arguably, the single most important role of the compassionate GP in palliative care is to help the person achieve a good death, the 12 principles of which were identified in the final report on The future of health and care of older people (Box 1).21

|

Box 1. Principles of a good death21

|

-

The ability to anticipate death and manage expectations

-

Access to any necessary information resources and support, both spiritual and emotional

-

Control over the situation, including pain relief, privacy, location of death and individuals present, combined with confidence that any predetermined instructions will be followed

-

Maintenance of a sense of dignity

-

Avoidance of needless prolonging of life, balanced with adequate time to say goodbye

|

People who are dying and suffering, whether physically, spiritually or existentially, take great comfort in being supported psychologically and feeling safe. By being their authentic selves, compassionate and empathetic GPs act as a powerful therapeutic tool to promote that outcome.

Most people fear the dying process and do not know what to expect.19 Honest, clear and reassuring communication that, with good care and symptom management, most people can die a comfortable death, can help to allay much of that fear.

Carers who have limited experience of death and dying processes also need compassion and support. It is reassuring for them to hear that they are doing a good job in difficult circumstances, particularly if their caring role has been extended to include symptom management and perhaps administration of subcutaneous medicines. To be prepared, they need to know what to expect as death approaches and what to do after death occurs.

2. The palliative care team

Palliative care requires a team approach to ensure best patient and carer outcomes.22 Most home-based palliative care teams are led and proactively coordinated by the GP. Team members vary and should be determined by patient needs and local availability of professionals. Members include clinicians such as nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, other allied health professionals and the local pharmacist. With more complex patients, specialist palliative care services may be enlisted to complement the skills of the local team.

The carer’s role is worthy of mention. Carers usually know the patient most intimately and are motivated to help. Carers are increasingly becoming embedded into resource-stretched palliative care teams to assume some responsibility for symptom management, particularly the preparation and administration of subcutaneous medications. When appropriately educated, they do this safely and with confidence.23,24

3. Available resources

There are now many freely available practical resources to support GPs to provide high-quality palliative care, some of which are listed in Table 1.

Not all GPs feel motivated to provide palliative care25 and so should organise alternative arrangements for their palliative patients.

|

Table 1. Practical resources to support GP provision of palliative care

|

|

Advance

|

A free toolkit comprising a training package and screening and assessment tools, Advance was created for Australian nurses working with GPs on the initiation of advance care planning and palliative care in general practice

|

www.caresearch.com.au/CareSearch/tabid/4031/Default.aspx

|

|

Advance Care Planning Australia

|

Provides healthcare professionals with resources such as advance care planning documents for each Australian state and territory

|

www.advancecareplanning.org.au

|

|

caring@home – Package for carers

|

Designed as an education resource to aid healthcare professionals when teaching carers how to safely manage breakthrough symptoms using subcutaneous medicines

|

www.caringathomeproject.com.au

|

|

ELDAC toolkits

|

Toolkits comprising a collection of information, resources and tools designed for people working in aged care. Topics focus on palliative care and advance care planning, and follow evidence-based recommendations or practices.

|

www.eldac.com.au/tabid/4889/Default.aspx

|

|

Opioid calculator

|

An opioid calculator app developed by Faculty of Pain Medicine, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists ANZCA

|

Download from App Store or Google Play

|

|

Palliative care symptom management medications for Australians living in the community

|

A consensus-based list of medications that are suitable for the management of terminal symptoms

|

www.caringathomeproject.com.au

|

|

palliMEDS

|

An app containing a consensus-based list of medications that are suitable for the management of terminal symptoms

|

Download from App Store or Google Play

|

|

Patient/carer information

|

CareSearch has many resources for carers and patients

|

www.caresearch.com.au/caresearch/tabid/64/Default.aspx

|

|

PEPSICOLA

|

An acronym for all the domains of a holistic assessment: Physical; Emotional; Personal; Social support; Information and communication; Control and autonomy; Out of hours

This can be used with other assessment tools to guide communication with patients and their families

|

www.caresearch.com.au/caresearch/tabid/4124/Default.aspx

|

|

PREPARED

|

An acronym to guide initiating end-of-life discussions with patients and families:

Prepare for the discussion; Relate to the person; Elicit patient and caregiver responses; Provide information; Acknowledge emotions and concerns; Realistic hope; Document

|

www.racgp.org.au/afp/2010/october/end-of-life-care/

|

|

SPICT

|

A tool that assists with the identification of people who have a higher risk of deteriorating and dying with one or multiple advanced conditions, thereby improving care planning and palliative care needs assessment

|

www.spict.org.uk

|

|

Symptom Assessment Scale (SAS)

|

A scale that can be used by clinicians as a checklist or screening tool when reviewing a patient. It can also be used by patients to monitor and report symptoms.

|

www.caresearch.com.au/caresearch/tabid/3389/Default.aspx

|

Conclusion

Palliative care is team-based care that sits well within the GP specialist scope of practice. Increasingly, GPs will be called on to deliver more palliative care for Australia’s growing and ageing population. To meet this demand, GPs can systematise three key clinical processes using three essential elements of palliative care to provide effective, efficient care for home-based palliative patients.

Case, part 1

Mary, aged 75 years, lives with her husband, Jack, who is aged 88 years and frail. Mary’s comorbidities include atrial fibrillation, diabetes, osteoporosis, arthritis, anxiety and chronic obstructive airways disease (COAD). Despite pulmonary rehabilitation and maximal pharmacotherapy, Mary’s COAD is progressively worsening. She has had three unplanned admissions in the past year, recent spirometry results of FEV1/FVC = 0.4, can only mobilise short distances and struggles with activities of daily living. She has lost 4 kg in the past two months without dieting.

She has an appointment for her Medicare Health Assessment for Older Persons (75+) and attends with her daughter, Ann. Mary went with Ann to a community talk about advance care planning and Mary asks you if this is applicable to her.

You show her a simplified diagram of the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool and explain that, on the basis of a number of important indicators, her health is worsening. You explain there is no crystal ball to determine anyone’s prognosis and that she and her family should talk about choices for her and Jack’s care into the future when their health fails.

Two weeks later, Ann brings her parents back for long appointments to discuss their advance care plans. Both want to remain at home for as long as possible and die there, if possible. Ann says she will take time off work to help. Neither want any heroic measures and want to avoid separation, nursing homes and hospital.

You organise home-care nurses, equipment and home help, while Ann organises meals-on-wheels and investigates care packages through the My Aged Care website.

Case, part 2

Two months later, Ann brings Jack to see you urgently. You find that Jack’s heart failure is worsening. Jack has increasing breathlessness, marked peripheral oedema and central cyanosis, and cannot sleep supine. Ann reports that, according to Mary, Jack’s implantable cardiac defibrillator fired last night. She also reports increasing periods of confusion, though currently he is lucid. There are no apparent reversible causes for his condition.

You explain that Jack’s heart is continuing to fail and that he may not have long to live. You ask Jack if he has changed his mind about any aspects of his advance care plan. He says no, he is tired and wants ‘to go’, and does not want any further treatment; his only concern is Mary.

You contact Jack’s cardiologist to consider having the defibrillator deactivated to avoid unnecessary shocks. You review his medications and prescribe morphine liquid for breathlessness.

Aligning with his wishes, you document a goals of patient care plan. Some particular points regarding Jack’s transition from restorative to palliative care include instructions:

-

to provide all comfort cares

-

not to provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation or invasive ventilation

-

not to transfer Jack to hospital

-

to only administer intravenous antibiotics or similar measures if consistent with Jack’s wishes and best medical practice.

You give Ann a copy of the plan to provide to the ambulance service if required and also provide one for the home-care team and your locum service.

Case, part 3

Four months later, Ann requests a home visit for Mary. Mary has been unable to get out of bed for two weeks because of breathlessness, in spite of home oxygen. She needs assistance with all cares and is not interested in food and refusing medications. She complains of tiredness, nausea and ongoing pain in her back and shoulders. She hardly talks at all. Both Mary and Ann are still committed to Mary dying at home, as Jack did.

You visit Mary and make a diagnosis of dying. After reviewing her goals of patient care plan, you:

-

arrange with home-care nurses to teach Ann how to manage subcutaneous medications for breakthrough symptom relief using the caring@home package for carers24

-

explain that Mary does not need to take her oral medications unless she improves clinically

-

prescribe and chart subcutaneous morphine for pain and breathlessness, metoclopramide for nausea and midazolam for anxiety or terminal restlessness

-

arrange for the home-care nurses to visit daily and provide Ann with a 24-hour telephone number in case she needs advice

-

provide Ann with ‘death at home’ documentation

-

discuss with Ann her impending bereavement and possibilities for support.

You leave a copy of your notes and planned management in Mary’s house so that everybody understands the terminal care plan.