Case

A man aged 19 years presented to a general practitioner (GP) with a one-day history of urinary frequency. There was no associated dysuria, macroscopic haematuria or urethral discharge. His history was unremarkable for previous urological conditions and sexual activity. On examination he was afebrile at 36.7°C. His abdomen was soft with no palpable masses, and examination of his genitalia was normal. A digital rectal examination was not performed. A urine dipstick indicated the presence of nitrites, leucocytes, blood and protein. A provisional diagnosis of urinary tract infection was made. The specimen was sent for microscopy, culture and sensitivities (MCS). The patient was prescribed trimethoprim 300 mg daily for seven days and advised he would need a follow-up appointment to discuss the MCS results and to arrange ultrasonography of his kidneys, ureters and bladder.

Incidentally, the GP noticed that the patient had a marfanoid appearance and obtained consent to examine for this. The patient’s height was 195.5 cm and weight was 64.3 kg, giving a body mass index of 16.82 kg/m2. He had long limbs with low muscle volume and long digits with hyperextendable joints. Inspection of the anterior chest revealed pectus carinatum and, to the GP’s surprise, a bounding apex beat on the right side of the chest within the fifth intercostal space. The patient’s left hemithorax was dull to percussion and had no breath sounds to auscultation. He was not tachypnoeic and had no increased work of breathing. It was noted that the patient was diaphoretic.

On further questioning, the patient admitted to worsening exertional dyspnoea for one month with associated orthopnoea when sleeping on his right side. He had also had a non-productive cough for the same duration. He had not sought medical advice for these symptoms as he attributed them to smoking, having smoked five cigarettes daily for the previous 1–2 years. He had not had any weight loss, had not travelled internationally and did not use recreational drugs. His alcohol intake was minimal.

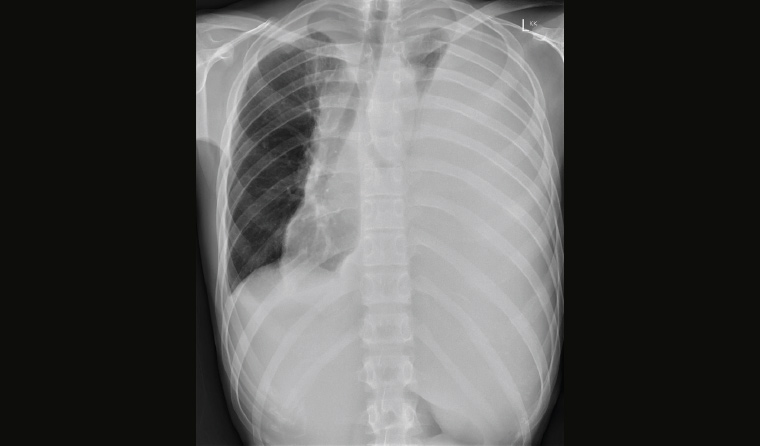

The GP expressed concern about a sinister thoracic pathological process and requested the patient have a chest X-ray performed that afternoon. Despite telephone call reminders, the patient delayed the X-ray (Figure 1) until the following week because of commitments, and in this time he had increased exertional dyspnoea.

Figure 1. Chest X-ray showing a large left pleural effusion and mediastinal shift to the right

Question 1

What are possible causes of a pleural effusion?

Answer 1

The causes of a pleural effusion are typically considered under the categories of transudates and exudates (Table 1) on the basis of assessment of the pleural fluid according to Light’s criteria.1

| Table 1. Causes of pleural effusions |

| Transudates |

Exudates |

- Heart failure

- Liver cirrhosis

- Kidney failure

- Hypoalbuminaemia

|

- Pneumonia

- Malignancy

- Pancreatitis

- Autoimmune disease

- Pulmonary infarction

- Subphrenic abscess

- Tuberculosis

- Chylothorax

- Medications

|

Case continued

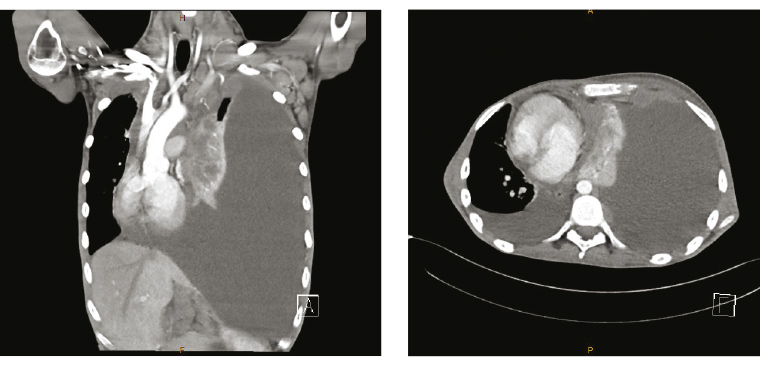

The GP was contacted by the radiologist to discuss the chest X-ray findings. They proceeded immediately to a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis (Figure 2), which provided additional findings of widespread lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly and sclerotic bone lesions. A provisional diagnosis of lymphoma was made on the basis of these findings; the patient was telephoned by the GP to inform him of the results and to arrange inpatient hospital admission via emergency. Formal urine MCS results, which identified a significant number of erythrocytes with no leucocytes and no pathogen isolated on culture, were also discussed. The urinary frequency and microscopic haematuria were attributed to the suspected lymphomatous process. During hospital admission, an additional history was elicited of three months of night sweats; an episode of epistaxis; and examination findings of palpable cervical, supraclavicular and axillary lymphadenopathy.

Figure 2. Computed tomography of the chest

The patient was admitted under the haematology unit and thoracentesis was performed. Work-up identified several abnormalities including hypercalcaemia, anaemia, coagulopathy, raised lactate dehydrogenase and raised C-reactive protein (Table 2). A cervical lymph node biopsy confirmed classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Staging was consistent with stage IV (advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma). The patient commenced doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) as his initial treatment regimen because of the ability to administer it rapidly. He was subsequently escalated to bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisolone (BEACOPP) for a planned six cycles. The GP arranged a referral to clinical genetics to pursue the Marfan diagnosis; however, the patient moved interstate and did not follow this up. Continuation of management of his lymphoma was transferred to his local haematology service.

| Table 2. Pathology results |

| Observation |

Value |

Reference range |

| Haemoglobin |

116 g/L |

135–180 g/L |

| White cell count |

9.8 × 109/L |

4.0–11.0 × 109/L |

| Platelet count |

367 × 109/L |

140–400 × 109/L |

| Haematocrit |

0.37 |

0.39–0.52 |

| Red cell count |

4.60 × 1012/L |

4.50–6.00 × 1012/L |

| Mean corpuscular volume |

81 fL |

80–100 fL |

| Neutrophils |

8.80 × 109/L |

2.00–8.00 × 109/L |

| Lymphocytes |

0.26 × 109/L |

1.00–4.00 × 109/L |

| Monocytes |

0.61 × 109/L |

0.10–1.00 × 109/L |

| Eosinophils |

0.06 × 109/L |

<0.60 × 109/L |

| Basophils |

0.02 × 109/L |

<0.20 × 109/L |

| International normalised ratio |

1.7 |

0.9–1.2 |

| Prothrombin time |

18 s |

9–13 s |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time |

33 s |

24–39 s |

| Fibrinogen (derived) |

5.0 g/L |

1.7–4.5 g/L |

| Sodium |

136 mmol/L |

135–145 mmol/L |

| Potassium |

3.8 mmol/L |

3.5–5.2 mmol/L |

| Chloride |

96 mmol/L |

95–110 mmol/L |

| Bicarbonate |

29 mmol/L |

22–32 mmol/L |

| Anion gap |

11 mmol/L |

4–13 mmol/L |

| Osmolality |

286 mmol/L |

275–295 mmol/L |

| Glucose |

5.6 mmol/L |

3.0–7.8 mmol/L |

| Urea |

3.8 mmol/L |

2.1–7.1 mmol/L |

| Creatinine |

73 mmol/L |

60–110 mmol/L |

| Urate |

0.37 mmol/L |

0.15–0.50 mmol/L |

| Protein |

65 g/L |

60–80 g/L |

| Albumin |

27 g/L |

35–50 g/L |

| Globulin |

38 g/L |

25–45 g/L |

| Bilirubin (total) |

11 μmol/L |

<20 μmol/L |

| Bilirubin (conjugated) |

5 μmol/L |

<4 μmol/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase |

92 U/L |

45–150 U/L |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

39 U/L |

<55 U/L |

| Alanine transaminase |

8 U/L |

<45 U/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase |

282 U/L |

120–250 U/L |

| Calcium |

2.54 mmol/L |

2.10–2.60 mmol/L |

| Calcium (corrected for albumin) |

2.80 mmol/L |

2.10–2.60 mmol/L |

| Phosphate |

1.36 mmol/L |

0.75–1.65 mmol/L |

| Magnesium |

0.70 mmol/L |

0.70–1.10 mmol/L |

| C-reactive protein |

96 mg/L |

<5.0 mg/L |

Question 2

What are typical presentations of Hodgkin lymphoma?

Question 3

How is the diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma confirmed?

Question 4

What is the staging system used?

Question 5

What is the significance of Marfan syndrome?

Answer 2

Typical presentations of Hodgkin lymphoma are asymptomatic lymphadenopathy, a mediastinal mass or ‘B symptoms’ (fever >38°C, weight loss and drenching sweats). A doctor must examine for lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly if these conditions are suspected. Hodgkin lymphoma has a bimodal age distribution with peaks among young adults and the elderly.

Answer 3

Histopathological diagnosis is required via tissue sampling, ideally using an excisional lymph node biopsy. A positron emission tomography/CT scan is required for staging, and a bone marrow biopsy is performed to assess marrow involvement.

Answer 4

The Cotswolds-modified Ann Arbor classification is used for staging.2 Stages are from I to IV with further sub-classifications. Patients may have early-stage disease (limited – stages I and II) or advanced-stage disease (stages III and IV). Early-stage disease is sub-classified into favourable and unfavourable depending on the presence of B symptoms, age and bulky disease. Disease stage is prognostic, in addition to several other patient parameters including age, sex and haematological parameters. Five-year survival for advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma ranges from 67% to 98% based on the patient’s International Prognostic Index score with ABVD treatment, and similar rates are reported for BEACOPP regimens.3

Given the favourable survival rates for patients with even highest-stage disease – especially in the fit, young patient population – a key focus is now management and prevention of longer-term therapy-related toxicities such as cardiopulmonary complications, as well as monitoring for secondary malignancies that may occur as a late complication of therapy.4 Novel targeted therapies currently in clinical trials promise to provide additional treatment options and reduce therapy complications.5

Answer 5

Individuals with Marfan syndrome should undergo monitoring for aortic dilatation, ectopia lentis, glaucoma, scoliosis and pectus deformities. They should receive genetic counselling and advice regarding appropriateness of pregnancy and high-intensity exercise given the risk of aortic dissection.6 There is suggestion that Marfan syndrome is associated with higher rates of malignancy.7

Key points

- Typical presentations of Hodgkin lymphoma are asymptomatic lymphadenopathy, a mediastinal mass or B symptoms.

- Histopathological diagnosis is required, ideally with an excisional lymph node biopsy.

- Given favourable survival rates, a key focus is now on monitoring and management of therapy-related complications.