A ‘good death’ is described as one with dignity and without suffering.1–3 While most patients have a straightforward and uncomplicated dying process, it is acknowledged that some symptoms including dyspnoea, agitation, nausea, terminal restlessness, pain and other physical symptoms can be challenging to manage.4,5 Where an exhaustive trial of available therapies fails, the symptom can be viewed as refractory. In these cases, early consultation with specialist palliative care services (SPCSs) can provide valuable support.

For symptoms that are both refractory and causing intolerable suffering (ie suffering that cannot be endured, thus causing distress) in the last days of life (ie the terminal phase), palliative sedation is reported in the medical literature as useful.4,5 Primary care doctors may be asked about palliative sedation for a patient in a residential aged care facility and may need to provide support to a family member of a loved one who underwent palliative sedation.

Palliative sedation has been defined as the deliberate reduction of consciousness of the patient to a level that adequately relieves refractory and intolerable suffering. It is different to brief and intermittent sedation, both of which are provided to restore tranquillity and then allow the patient to regain consciousness. The intent of palliative sedation is to relieve the severe and persistent distress caused by refractory and intolerable symptoms without shortening the length of life, which distinguishes it from physician-assisted suicide (PAS) or euthanasia. It is a last-resort intervention requiring multidisciplinary planning and extensive discussions involving the patient, multidisciplinary team (MDT), carer and family members. Palliative sedation is performed in an inpatient specialist SPCS setting under the guidance of an MDT experienced in caring for patients in the terminal phase. However, literature has documented the use of palliative sedation in Europe by primary care doctors within a nursing home setting as well as a home setting, under the guidance of SPCSs.6–8 Standardised guidelines for use by SPCSs worldwide have been developed,9–11 with the European Association for Palliative Care framework being the most commonly used guideline.12,13

The following case involved a patient in a tertiary centre who died at the centre. Much of the information in this article focuses on tertiary centre care. However, the authors hope this provokes thoughts on the future role of primary care doctors’ involvement in this uncommon intervention.

Case

AW, aged 74 years, was an independent retired long-distance truck driver who lived with his wife. He presented to the tertiary hospital emergency department in April 2018 with fever, confusion and dyspnoea. His relevant past medical history included a diagnosis of lambda light chain myeloma in May 2017, for which he received treatment until three months prior, at which point the treatment stopped working. Further treatment for the myeloma was unavailable. AW was diagnosed and treated for sepsis from a community-acquired pneumonia with concurrent hypercalcaemia from his myeloma. He was admitted to a haematology ward for ongoing monitoring and treatment.

Despite aggressive treatment of pneumonia and dehydration, he developed multi-organ failure, at which point discussions with family led to a decision to aim for comfort rather than to prolong life. He was no longer fully conscious nor cognitively able to make decisions. With the aid of his advance care directive (ACD) and family, the decision for comfort measures was made. He was referred to the local SPCS.

Although AW continued to be cared for by the haematology team, the SPCS oversaw the commencement of a continuous subcutaneous infusion (CSCI) of hydromorphone and midazolam, mainly for dyspnoea and pain. This route was appropriate as his semi-conscious state affected his ability to swallow. Deterioration into the terminal phase was imminent. Despite treatment with hydromorphone and midazolam, symptoms progressed, with the addition of terminal restlessness and agitation. The opioid and benzodiazepine doses were increased, and haloperidol was added. Despite this, as well as multiple breakthrough doses, the symptoms continued. After thorough assessment, it was clear that AW had refractory and intolerable symptoms. The symptoms of dyspnoea, pain, agitation and restlessness were so severe that the patient tried to climb out of bed and continuously injured himself on the bed railings. Thorough assessment involved ruling out urinary retention, severe constipation, medication side effects and withdrawal from underlying substance abuse.

Nursing staff on the general medical ward expressed unease that medications being used at the current doses would hasten death for AW. This led to a series of events that could have been avoided, including a delay in medication administration. Ultimately the palliative care team administered the doses that were needed.

The family were also upset by AW’s level of discomfort, and the concept of disproportionate sedation was discussed to ensure his comfort needs would continue to be met. The discussion involved initiating deliberate sedation with an infusion of a medication at a safe but sedative dose. This was different to commencing breakthrough doses of medications and up-titrating to effect. The family gave consent for AW to be sedated. The potential benefits and burdens of palliative sedation and artificial hydration were given, resulting in the decision to withdraw artificial hydration. It was explained that this was a way of controlling his symptoms of distress without shortening his life. A dedicated nurse was employed so that his symptoms could be monitored. AW’s care was transferred to the SPCS and he was transferred to the palliative care inpatient unit.

For sedation, levomepromazine was initiated in a second CSCI and breakthrough doses were charted. Haloperidol was ceased. AW was also charted for phenobarbitone when required. AW had 24 hours of a peaceful and sedated state. He died with the family around him soon after. Follow-up from the bereavement team was organised. Regarding the distress from the nursing staff on the non–palliative care ward, a teaching and debriefing session was organised to allow for discussion of the important concerns raised.

Indications and patient assessment

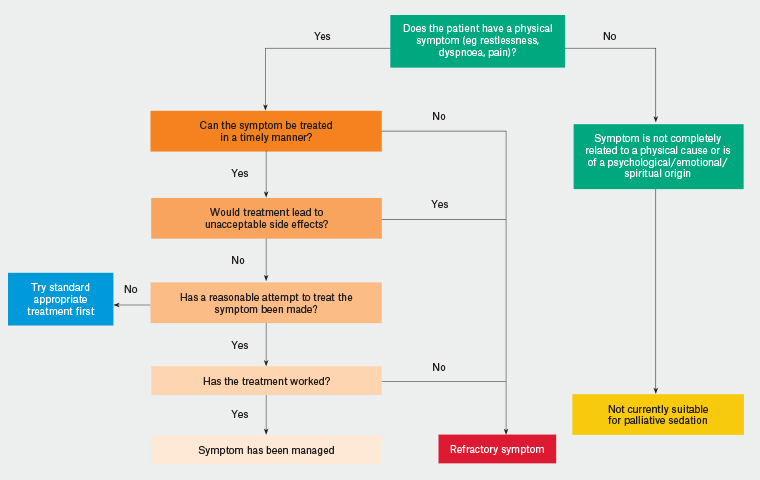

Palliative sedation is reserved for refractory and intolerable symptoms in patients with a life-limiting illness of <2 weeks’ predicted prognosis (Figure 1).6 There is inherent uncertainty when it comes to prognostication. However, the combination of abnormal vital signs, biochemistry and other symptoms such as dysphagia, oedema, cognition, sedation and ascites provides some level of guidance to come to this decision.14 There was evidence of abnormality in all of these aspects in the case reported. It is important to distinguish refractory symptoms from difficult-to-treat symptoms.15 To adequately identify refractoriness and intolerability, a detailed assessment should be carried out by an MDT to define the symptom in relation to its different attributes (eg physical, psychosocial, emotional, spiritual).16,17 The family may be able to provide some insight into this. Additionally, the symptom must be deemed untreatable by available methods in the existing timeframe, or potential treatments must carry risks or side effects that are unacceptable. Comorbid states such as mental health problems (eg major depression) can complicate the clinical picture, which is why assessment by multiple specialities is critical for a symptom to be deemed refractory.

Figure 1. An algorithm to aid in determining whether a symptom is refractory

Preparation prior to initiation

Ideally, palliative sedation is well planned and executed following detailed discussion with the patient (or their family members, if the patient is cognitively impaired). Preparatory conversations ensure adequate planning, particularly where palliative sedation is felt likely to be needed later in the course of the illness, so that the patient can indicate their wishes clearly when that time comes, in line with patient autonomy. It is important to reiterate and document that the purpose of palliative sedation is for symptom relief. Unfortunately, the events in AW’s case were so rapid that the patient was not involved in these decisions, but the family were able to express what his wishes would have been.

It is suggested that the following points are discussed prior to initiation of palliative sedation in the tertiary setting, and the extent of this conversation should be clearly documented. In the documentation, it is important to include who was present and the final decision regarding treatment. In addition, there should be evidence that the following have been acknowledged and documented:18

- the current state of the patient and the cause of distress

- discussions with an SPCS

- the patient’s wishes as expressed in their own words (if the patient is still alert and conscious)

- completion of an ACD

- estimated life expectancy

- the purpose of palliative sedation and the theoretical risks involved

- treatments already tried to alleviate distress

- the details of palliative sedation that will be used such as level of sedation, monitoring and weaning (if appropriate)

- discussion about hydration and nutrition

- informed consent for treatment to proceed

- anticipated bereavement complications of carer or family.

It should be noted, however, that primary care doctors are not expected to have this information available when calling an SPCS team.

The process of informed consent is vital from a medico-legal point of view and should, if able, involve the patient, an MDT and the family.18 It is important to allow time for questions to be asked and answered by patients, family members and carers.

Palliative sedation as a procedure

When palliative sedation is used appropriately, the choice of medicines used for patients is individual to the patients’ needs and the type and level of distress that is being addressed. Pharmacological options that exist are presented in Table 1, listed from most common to least common sedative medication.

| Table 1. Details of suggested pharmacological options for palliative sedation57 |

| Medication |

Comments |

| Midazolam |

- Tolerance to the sedative effects of midazolam may occur.

- The dosage may need to be increased over time.

- Paradoxical excitation to midazolam may occur (2% incidence).

- If there is inadequate symptom control or incomplete sedation with maximum doses, then additional agents may be of greater benefit rather than further increases to the dose of midazolam.

|

| Levomepromazine |

- This medication is useful if the individual has significant nausea or delirium.

- It may lower seizure threshold.

- Extrapyramidal side effects may appear.

- It is listed on the Special Access Scheme and requires specific paperwork.

|

| Phenobarbitone |

- This medication requires individualised dosing because of considerable variability in pharmacokinetics.

- Injection site reactions such as tissue necrosis can occur.

- It can be used in cases of inadequate response to benzodiazepines and levomepromazine.

|

| Propofol56 |

- Intravenous access is required.

- Propofol may need input from intensive care anaesthetists or general practitioner anaesthetists.

- It should only be considered if all options have failed and the patient has reached their last days of life.

|

In monitoring palliative sedation, the goals relate to comfort and safety, and monitoring needs to reflect this.12,19,20 This can cause a level of discomfort for staff members who are based outside an inpatient palliative care unit.21 While an inpatient palliative care unit commonly oversees this treatment and is an ideal setting,21 literature suggests that the prevalence of palliative sedation varies widely between 1% and 88%, which may be in part due to differences in care settings.22 However, it is important to note the lack of consistency between some of these studies, in that the studies reporting a higher prevalence of palliative sedation used any sedating medications as a definition of palliative sedation.

There are currently no specific scales to assist with the assessment of depth of sedation in terminally ill patients.20 While the Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS; Table 2)17,21 has been used, it is not validated for palliative sedation therapy.12,19,20,23 The RASS was developed for intensive care patients to assess the level of sedation and agitation. Although palliative sedation has been safely used for terminally ill patients, more research needs to be undertaken to assess the validity of existing scales.24 Another scale is the bispectral index score.25 Monitoring initially involves 20-minute checks until adequate sedation that controls distressing symptoms has been achieved, after which checks are performed three times per day.12 If deep sedation is required, then a score of –3 or –4 on the RASS is acceptable. While sedation may be used for refractory pain, it is important to continue opioids for their analgesic effect, while noting their additive sedative effects. Therefore, pain must also be assessed during palliative sedation, and the Nociception Coma Scale26 is an appropriate scale to use for this purpose. A score of ≤8 is ideal for people receiving palliative sedation. Indeed, the toxic effects (eg myoclonic jerks, pinpoint pupils) of the opioid will need to be closely monitored and dosage adjusted accordingly.

| Table 2. Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS)23 |

| Score |

Term |

Description |

| +4 |

Combative |

Overtly combative or violent; immediate danger to staff |

| +3 |

Very agitated |

Pulls on or removes tube(s) or catheter(s) or has aggressive behaviour toward staff |

| +2 |

Agitated |

Frequent nonpurposeful movement or patient–ventilator dyssynchrony |

| +1 |

Restless |

Anxious or apprehensive but movements not aggressive or vigorous |

| 0 |

Alert and calm |

|

| −1 |

Drowsy |

Not fully alert, but has sustained (>10 seconds) awakening, with eye contact, to voice |

| −2 |

Light sedation |

Briefly (<10 seconds) awakens with eye contact to voice |

| −3 |

Moderate sedation |

Any movement (but no eye contact) to voice |

| −4 |

Deep sedation |

No response to voice, but any movement to physical stimulation |

| −5 |

Unarousable |

No response to voice or physical stimulation |

| Reproduced with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2018 American Thoracic Society. The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society. |

Practical considerations

Palliative sedation is a procedure that renders the patient completely dependent, which is why it is important that it is carried out in an appropriate environment with adequate supports in place.

Quite commonly in palliative medicine, families will ask about hydration and nutrition, especially in the end-of-life phase. This may be more evident in palliative sedation given that the patient will be unable to swallow. One important point to make is that many patients who receive palliative sedation have already stopped hydration and nutrition, most likely due to a deterioration and decline from their terminal illness.27 Nonetheless, a number of studies report no benefit with artificial hydration and nutrition for terminally ill patients, and many clinicians consider this to be prolonging life and hence prolonging suffering.21,28–30 Artificial hydration should be approached on a case-by-case basis, as individual cultural, religious and psychological factors may have an impact on the long-term outcome.19,27,31

Routine nursing assessment of bowel and bladder function, as well as eye, mouth and skin care, are still required for patients having palliative sedation. Restlessness and distress can be caused by urinary retention and severe constipation. It is important to monitor this as these concerns can be treated effectively with appropriate strategies.

Ethical issues

Ethical issues in palliative sedation are complex, such that in some literature, palliative sedation is still described as controversial.7–12 Controversies include the distinction of palliative sedation from PAS;15–19 the unavoidable morbidity of palliative sedation; and the request from families to initiate palliative sedation on behalf of their loved one, citing a perception of suffering, when in fact it is the family that is suffering.21,32 Emphasising that palliative sedation exists to be used in the last days of life is important. There are also issues surrounding consent, level of sedation, timing of intervention, indications and how to sedate.19,33 Gurschick et al19 have recognised these inconsistencies and made recommendations to simplify matters, including: using the term ‘palliative sedation’ to mean a certain depth and pattern of sedation; accepting that indications of non-physical symptoms will vary between practitioners; specifying medications and doses; and formulating an algorithm for administration.19 There are some suggestions of clinicians using palliative sedation to hasten death,12,34 which is deemed an unethical and illegal deviation from normal practice. Conversely, there are also suggestions of clinicians withholding palliative sedation over-judiciously while pursuing therapeutic options that are unlikely to have a beneficial effect.12

Palliative sedation is intended to relieve intractable suffering, while the intent of PAS is to terminate a patient’s life;21,24,35 success of palliative sedation is defined by control of symptoms, not death.8 While studies have shown that palliative sedation does not seem to hasten death in the majority of patients,24,35 the retrospective nature of these data leaves some clinicians uncertain about the effects of palliative sedation on hastening death.14,15 Ethically, this potential for shortening life can be viewed within the lens of the doctrine of double effect,36,37 which describes an act as morally acceptable if the intent is a good outcome even if the resultant outcome is bad. In palliative sedation, the negative outcomes of loss of social interaction and potentially hastened death are outweighed by the relief of refractory and intolerable suffering. These issues highlight the need for a thorough discussion with patients and caregivers about palliative sedation, emphasising the goal as a reasonable therapy to relieve refractory symptoms.

Palliative sedation for existential distress is an area of debate and controversy, and it is unfeasible to examine fully these issues in this article. Existential distress is an experience characterised by feelings of hopelessness, isolation and being a burden on others that often affects people with an advanced terminal illness.38 Existential distress may be associated with physical symptoms and can adversely affect the patient’s level of distress, so it must be considered as part of the assessment.

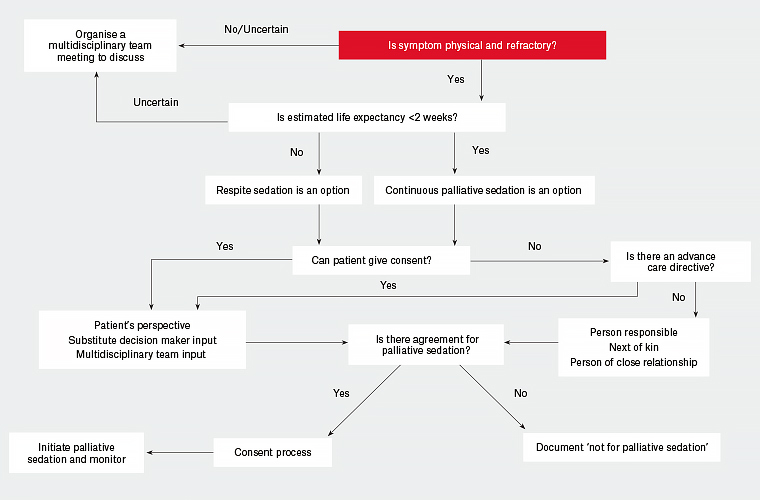

Figure 2 provides an algorithm for initiating palliative sedation in a hospital setting.

Figure 2. A suggested algorithm to the approach of initiating palliative sedation in a patient with physical and refractory symptoms in their advanced terminal illness

Support for care providers and family members

It is important to look at and understand clearly the healthcare professionals’ perspectives regarding palliative sedation as there are often reports of moral distress and emotional, spiritual and ethical burdens.39,40 Studies have shown that moral distress was evident among nurses when they felt they were not acting in the patient’s best interest.41 Patel et al reported that nurses believed that palliative sedation requires a unique set of skills that must be learned,39 primarily as the focus becomes dealing with the distress of the patient and the family. Within the literature, nursing staff’s unease with palliative sedation relates to confusion regarding how to define palliative sedation, including concerns over the use of medications for symptoms as opposed to palliative sedation,42 and that palliative sedation is akin to PAS.43 The emotional burden can be high when caring for a dying patient, and this can escalate when therapy such as palliative sedation commences. To relieve this burden, it may be beneficial to employ a team approach to resolving conflicting opinions and coordinating early family meetings and adequate education and training relating to palliative sedation.39,42 Other health professionals’ opinions may influence health professionals who are considering providing palliative sedation; therefore, encouraging patient-centred care may be a method to manage the conflict.40 Overall, there is little evidence about the palliative sedation–related emotional burden in healthcare professionals.44 From existing studies, there appears to be a high level of variability between the medical and nursing experiences of palliative sedation as well as experiences between different countries.45,46

Empirical studies have shown that approximately 50% of patients can actively participate in discussions regarding palliative sedation.47,48 Relatives are usually involved in palliative sedation decision making; however, the use of palliative sedation can be psychologically and spiritually disturbing for relatives.49,50 An observational study has shown that the use of palliative sedation has no overall negative influence on the relative’s experience of the dying phase of their deceased relative or on their own wellbeing after the relative’s death.51 Nonetheless, owing to the complex and ethical issues surrounding palliative sedation, it is vital to impart adequate and appropriate information to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression.52,53 While Bruinsma et al showed that most relatives were given good and adequate information,51 this differs to previous studies that highlighted inadequate provision of information and poor communication about palliative sedation.54,55 Referral for early bereavement support is vital following the death of loved ones, especially following a therapy such as palliative sedation.52

Implications for practice

Primary care doctors may be involved in MDT meetings discussing palliative sedation for their patients in a hospital setting. Alternatively, family members whose loved ones have required palliative sedation may need to be followed up and monitored for psychological and moral distress, which is why it is important for general practitioners to be aware of this therapy.

Palliative sedation is complex. There is currently no Australian palliative sedation framework for primary care doctors to apply in different clinical settings (eg home, residential homes and rural/remote areas). Implementation in rural settings and other low-resource environments would require careful adaptation of the current guidelines including reference to the potential role of telehealth.

Conclusion

Palliative sedation is an important, evidence-based, effective therapy. Guidelines are available to healthcare professionals on when and how to initiate this therapy in an acute care setting. However, it remains a vastly complex form of therapy with significant ethical, emotional and professional issues.

Summary

- Palliative sedation is a method of sedation used for patients in the terminal phase that induces a state of reduced or complete consciousness to minimise the distress caused by refractory and intolerable symptoms.

- The intent of palliative sedation differs from euthanasia or PAS in that its goal is symptom relief without hastening death.

- Palliative sedation is a third-line intervention reserved for people with refractory and intolerable symptoms who have <2 weeks’ life expectancy (terminal phase).

- Obtaining informed consent through adequate discussions and documentation relating to the aims, benefits and goals is necessary prior to initiating palliative sedation.

- Monitoring relief of distress, depth of sedation and side effects should be tailored to the clinical setting.

- Those involved in palliative sedation should be monitored for psychological and moral distress.