Pancreatic cancer has the highest mortality rate among all main cancer types. It is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in Australia, with a one-year survival rate of approximately 20% and five-year survival rate of 8%, and is projected to become the second leading cause of cancer death by 2030.1,2 This year in Australia, 3400 people will receive a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, of which 3000 will die. Over the past 40 years, the incidence of pancreatic cancer in Australia has increased from 9.6 in 100,000 to 11.6 in 100,000.1

Risk factors

Approximately 95% of pancreatic cancers arise from the pancreatic duct, and this review will focus on diagnosis and management of this form of pancreatic cancer. The most important risk factor for pancreatic cancer is increasing age, with risk rising to one in 61 by the age of 85 years.1 Factors that increase the risk less than five-fold include smoking, obesity (body mass index >30 kg/m2), heavy alcohol use (>4 standard drinks/day), long-standing diabetes (>5 years), one first-degree relative (FDR) with pancreatic cancer, BRCA1 gene carrier status, Lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis.3,4 Factors that increase the risk 5–10-fold include two FDRs with pancreatic cancer, BRCA2 gene carrier status, chronic pancreatitis and cystic fibrosis. Factors that increase the risk more than 10-fold include hereditary pancreatitis with PRSS1 mutation, family history of ≥3 first-, second- or third-degree relatives with pancreatic cancer, Peutz–Jeghers syndrome and familial atypical multiple mole syndrome. Approximately 5–10% of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer have a family history of the disease.3 Individuals with pancreatic cancer risk increased more than five-fold may be referred to a familial cancer service for consideration of imaging surveillance, including those with Lynch syndrome or BRCA2 mutation and at least one affected FDR.5,6 There is no screening test for individuals with standard or mildly increased risk.

Presentation, diagnosis and indication for specialist referral

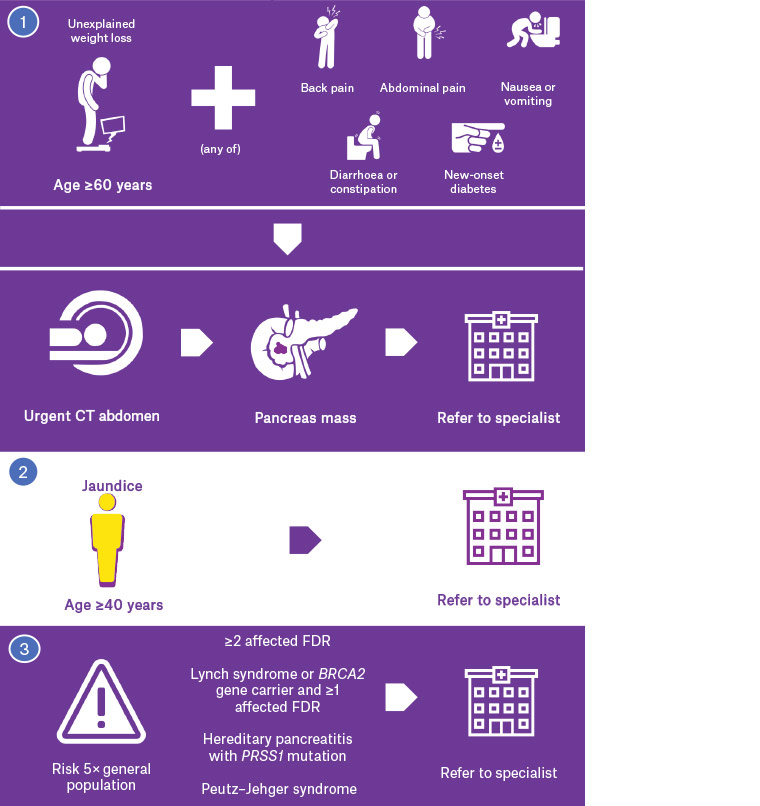

There are no cardinal symptoms for pancreatic cancer, and no screening test for early detection in the general population. Symptoms overlap with other benign and malignant diseases, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines recommend investigation when the risk of malignancy is >3%.7 Considerable work has been done in the primary care setting to identify symptoms that are associated with a risk above this threshold, with an online risk calculator now available (https://qcancer.org).8,9 The diagnosis of pancreatic cancer requires cross-sectional imaging, preferably using a pancreas protocol computed tomography (CT) scan. Imaging is performed by taking thin axial slices through the pancreas in non-contrast, arterial and venous phases. On the basis of these guidelines, symptoms in patients ≥60 years of age that indicate the need for urgent (within two weeks) CT of the abdomen are weight loss combined with any of: back or upper abdominal pain, diarrhoea (in particular steatorrhea), constipation, dyspepsia, nausea and vomiting, and new-onset diabetes (Figure 1).10 New-onset jaundice in patients aged ≥40 years has a risk of malignancy that is >20%, and urgent specialist referral is required.9 This should not be delayed by waiting for imaging or other results. Urgent referral (within one week) to a specialist linked with a multidisciplinary team is indicated when imaging shows a pancreatic mass, or there is unexplained dilatation of the pancreatic and/or bile duct. Dedicated pancreatic imaging is used to determine resectability on the basis of the relationship between the mass and major vascular structures. Endoscopic ultrasonography is increasingly being used to gain a tissue diagnosis following dedicated pancreatic imaging.

Figure 1. Presentation, diagnosis and indications for specialist referral for pancreatic cancer

CT, computed tomography; FDR, first-degree relative

Staging

Approximately 20% of patients present with disease that is limited to the pancreas and potentially resectable (stage 1–2), while approximately 50% present with metastatic disease (stage 4).11,12 The remaining 30% present with disease that interfaces with major vascular structures, making it either borderline resectable or locally advanced (stage 3). Metastases most commonly are to lymph nodes outside standard lymphadenectomy stations, peritoneum, liver and lungs, and may be identified by CT.13 Magnetic resonance imaging is more accurate for characterising indeterminate liver lesions.14 Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT is increasingly being used to determine staging and may change the treatment plan for up to 20% of patients.6 Use of PET/CT in this setting varies between institutions and is not currently considered standard care for all cases. Indeterminate extrapancreatic lesions are commonly identified by staging imaging, and it can be unclear whether they represent metastatic disease, a second primary neoplasm or an unrelated benign lesion. These lesions may be further investigated with endoscopic ultrasound–guided fine needle aspiration, staging laparoscopy or short-interval imaging. Serum CA 19-9 should routinely be measured as a tumour marker once a probable or definitive diagnosis has been made, noting it may also be elevated in the setting of biliary obstruction or cholangitis.15 CA 19-9 should not be used as a screening test for patients without a cancer diagnosis, as its role is in staging of disease, monitoring response to therapy and conducting post-treatment surveillance to detect and diagnose recurrence. Tumour markers currently are not used as a threshold to access specific treatments, although a biomarker response to systemic therapy is a good prognostic indicator.

Treatment

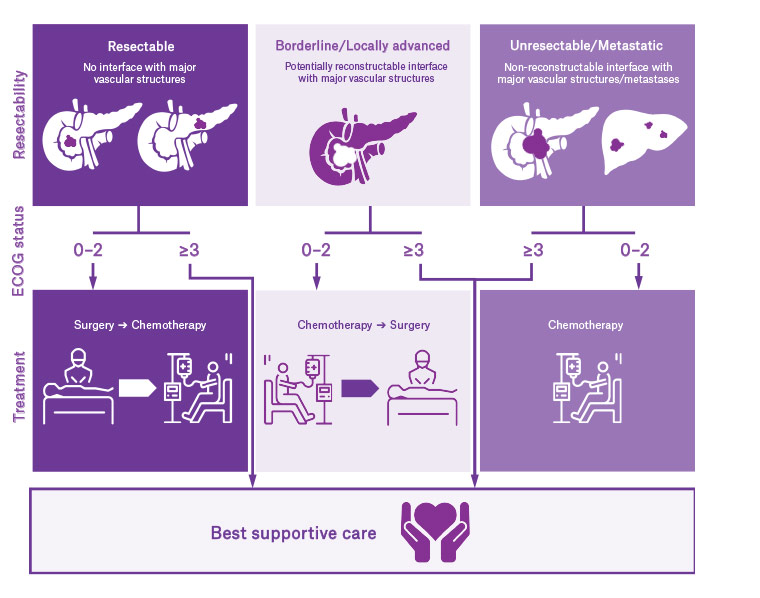

Treatment is based on the stage of the disease, the performance status of the patient and the treatment goals of the patient and their family (Figure 2). Patients with resectable disease and good performance status are offered surgical resection. The current paradigm for these patients is to proceed with surgery first followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with borderline resectable or locally advanced disease and good performance status are offered neoadjuvant chemotherapy +/– radiotherapy, followed by surgical exploration and resection if appropriate. Patients with metastatic disease and good performance status are offered palliative treatments including chemotherapy and surgical bypass, while patients with poor performance status are managed with best supportive care. Biliary drainage is often required for tumours located in the head of the pancreas, independent of stage. In general terms, any patient with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 3 (confined to a bed or chair for >50% of time during the day) or higher will not benefit from surgery or chemotherapy, and should be offered best supportive care. Each treatment modality is discussed in this article.

Figure 2. Treatment algorithm for pancreatic cancer

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Biliary drainage

Patients with a cancer located in the head of pancreas may present with jaundice and require biliary drainage. This is most commonly achieved endoscopically with plastic or self-expanding metal stents, with the latter having higher patency rates and a reduced need for repeat biliary intervention.16 Not all patients with jaundice require biliary drainage prior to surgery, with evidence showing a lower complication rate if surgery is completed without biliary stenting.17 Therefore, patients with jaundice should be referred to a pancreatic surgeon prior to stenting. If unresectable or metastatic disease is found during surgical exploration, biliary bypass may be performed. Surgical bypass is associated with longer survival and fewer interventions than stenting alone, and may be used in patients with good performance status who are expected to survive >6 months.18

Surgery

There are three main pancreatic resections – pancreaticoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy and total pancreatectomy – with the type of resection determined by the location of the tumour. These procedures have become standardised in terms of the extent of resection and lymph nodes retrieved.12 Portal or superior mesenteric vein resection is performed in approximately 20% of pancreaticoduodenectomies.19 The perspective on surgical management after neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced disease is not standardised, and ranges from no role for surgery through to multivisceral resection with vascular reconstruction. Arterial resection for pancreatic resection remains controversial but is being performed with success in highly selected patients.20,21 Since involvement of major visceral arteries is often a key determinant of resectability, early dissection along the arteries has become an important principle that may be associated with improved perioperative outcomes.22 Distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer mandates splenectomy in order to achieve the required lymphadenectomy, and appropriate vaccinations should be administered preoperatively. Total pancreatectomy results in type 3c diabetes, which is characterised by pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency.23 This form of diabetes requires ongoing input from an endocrinologist, and patients who are to undergo total pancreatectomy should have endocrinology review prior to surgery. There is a volume–outcome relationship for pancreatic surgery, likely due to a higher rescue rate for patients with complications in high-volume centres.24 In Australia, high-volume centres are defined as those performing ≥10 pancreatic resections per year.25

Chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy is the current standard of care for patients with resected pancreatic cancer. Single-agent gemcitabine has some survival benefit, particularly for patients with marginal performance status; however, multi-agent regimens provide better survival advantage. FOLFIRINOX (fluorouracil, folinic acid, irinotecan and oxaliplatin) improves disease-free survival when compared with gemcitabine alone (21.6 months versus 12.8 months) but is associated with increased toxicity.26,27 Gemcitabine plus oral capecitabine is superior to gemcitabine alone (overall survival of 28.0 months versus 25.5 months).28 The use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for resectable disease is of uncertain benefit, although there is a trend towards increased use.29 For borderline resectable disease, neoadjuvant chemotherapy has become the standard of care.11 In this setting, approximately 15% of patients will have disease response on imaging, approximately 15% will have progressive disease and the remainder will have stable disease. Following neoadjuvant therapy, most centres now recommend surgical exploration in patients with good performance status who have non-progressive borderline resectable disease.12 The management strategies for locally advanced disease differ greatly between centres. There is a clear role for chemotherapy in unresectable and metastatic disease, with multidrug regimens showing increased survival benefit but also potential increased toxicity. The main factors determining selection of the chemotherapy regimen are treatment intent, patient performance status and patient choice based on side-effect and adverse-event profile.

Radiotherapy

Currently, radiotherapy is not standard care for patients with resectable disease, although it has been used after resection with positive margins.30 However, this approach is not used in all centres as the survival benefit compared with chemotherapy alone is uncertain.31 The role of neoadjuvant radiotherapy for resectable pancreatic cancer is not clear, although emerging data are encouraging.32 Neoadjuvant radiotherapy alone should not be used in the setting of borderline resectable or locally advanced disease, as survival is inferior to that seen in combination with chemotherapy.8 For unresectable or metastatic disease, palliative radiotherapy is generally reserved for specific symptoms, such as pain, or local control for compressive symptoms.33

Ablative therapies

Ablative therapies have been used for unresectable pancreatic cancer for several years. Most recently, irreversible electroporation (IRE) has been used for this purpose and has shown promising results.34 IRE has been used to increase the rate of complete resection in borderline resectable and locally advanced tumours, and also to ablate unresectable tumours. Currently it is not a considered standard treatment and is the subject of ongoing clinical trials.

The role of molecular and genetic profiling

Germline genetic testing has, for a minority of patients, allowed targeted treatment for pancreatic cancer, such as the use of platinum-based chemotherapy in the presence of BRCA mutations.35 Individuals diagnosed at <50 years of age, of Ashkenazi Jewish ethnicity or with a strong family history of colorectal, breast or ovarian cancer should be considered for referral to a family cancer clinic. Somatic molecular or genetic profiling is being used in a small number of centres, with emerging evidence indicating that this information may be successfully used for a precision oncology approach.36,37 However, profiling of pancreatic cancer remains an area of research and is not standard practice.

Nutritional and pain management

Most patients with pancreatic cancer develop nutritional compromise, and many present with significant weight loss, which affects outcomes. Sarcopenia is a risk factor for poor outcomes after pancreatic resection.38 All patients with unresectable or metastatic disease require enteric-coated pancreatic enzyme replacement.6 Enzymes should be considered before and after pancreatic resection. Faecal elastase may be used to determine the level of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. Pain management is an important part of pancreatic cancer care and may require input from oncology and palliative care specialists. Coeliac plexus neurolysis should be considered to manage pain.6 Early referral to palliative care services allows for prompt management of symptoms and provides additional psychological support for the patient and their family.

Prognosis and follow-up

The prognosis for pancreatic cancer remains poor, with a five-year survival of 8% in Australia.1 Patients with metastatic disease who receive chemotherapy have a median survival of 12 months, while those who receive best supportive care have a median survival of <6 months.12 Patients who undergo resection and adjuvant therapy have a median survival of 20–28 months. Quality of life after pancreatic resection improves over time, although it does not approach that of the general healthy population, with gastrointestinal dysfunction remaining a significant source of symptoms.39 Progressive gastrointestinal dysfunction should precipitate surgical referral. Follow-up is based on the stage of disease and treatment intentions. The role of follow-up is to identify new, unexplained or unresolved symptoms that can be further investigated or better managed.6 However, evidence that surveillance imaging prolongs survival is very weak at best, and therefore no strong recommendations can be made. National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend CT scanning and CA 19-9 testing every 3–6 months for two years, with the acknowledgement that data are not available to show that this leads to better outcomes.11 Historically, survivorship care plans (SCPs) have not been commonly used in the setting of pancreatic cancer, although these are now considered an essential part of quality cancer care.40 SCPs should detail the type and stage of cancer, treatments received, plan for type and frequency of surveillance testing, and information on supportive care and rehabilitation. Symptoms of recurrent or progressive disease include abdominal or back pain, abdominal distension, jaundice and weight loss.

Key points

- No cardinal symptoms for pancreatic cancer exist, but weight loss combined with a wide range of abdominal symptoms in individuals aged ≥60 years prompts urgent CT of the abdomen, while individuals aged ≥40 years with jaundice require direct specialist referral without waiting for imaging results.

- Pancreatic cancer is categorised as resectable, borderline resectable, locally advanced or metastatic.

- Resectable disease is treated with surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Borderline resectable and locally advanced disease is treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy +/– radiotherapy, followed by surgical exploration and resection if non-progressive.

- Metastatic and unresectable disease is treated with chemotherapy or best supportive care.

- Nutritional support and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy is required for most patients.

- Pain control is a crucial part of pancreatic cancer management.