In Australia, men and women aged 65 years can expect to live for another 20 and 22 years, respectively.1 To optimise their ageing experience, a focus on strategies that enable older people to maximise their functional ability, maintain their independence and reach their potential is needed. This approach is promoted in the World Health Organization’s World report on ageing and health.2

This article discusses ‘reablement’ and ‘restorative care’, relatively new terms appearing in Australian Government policy and in programs that target functional decline in older people.3,4 These programs work best when a comprehensive, function-focused approach is adopted, in which the general practitioner (GP) has a key role.

Functional ability and ageing well

Functional ability is determined by an individual’s intrinsic capacity and the environment with which they interact.2 Intrinsic capacity has been defined as the combination of the physical and mental capacities of an individual.2 The environment refers to an individual’s home and the community and society more broadly, and includes available assistive technologies and the built environment.2

As a person ages, their intrinsic capacity is influenced by genetic factors, the cumulative effects of illness and injury, and the social determinants of health, over their life course.2 Health-promoting behaviour (eg maintaining physical fitness and building cognitive reserve), disease prevention and optimal disease management throughout life and into older age are central to maximising and retaining intrinsic capacity.

From mid-adulthood, intrinsic capacity tends to decline with age.2 At a population level, the average decline with age is gradual; for an individual, the trajectory is variable, with intermittent dips (from illness or injury) followed by a level of recovery.2 The degree to which an individual’s functional ability is affected is dependent on how well intrinsic capacity has been maintained or can be regained and the degree of compensation that can be provided through an enabling environment.

Reablement, restorative care and rehabilitation

Attention to a person’s functional ability is not a new concept and is central to the approach of rehabilitation medicine. In Australia, rehabilitation generally applies to time-limited hospital-based (or affiliated) programs that follow acute illness or injury, funded within the healthcare system. It involves the diagnosis and clinical management of the underlying causes of functional loss, the assessment of function using validated tools, collaborative goal setting, evidence-based interventions delivered using a multidisciplinary approach, and the use of environmental modifiers, particularly assistive technologies and home modifications, to maximise intrinsic capacity and functional ability.

Reablement and restorative care are terms now appearing in the international lexicon, but they remain variously defined and are often applied interchangeably and inconsistently.5,6 Like rehabilitation, these terms are used to refer to time-limited programs that aim to maximise functional ability, but such programs differ from rehabilitation in location, intensity, skill mix of the practitioners, funding source and, to some extent, intent.

In Australia, reablement and restorative care programs are mostly less intense than rehabilitation, are usually directed by allied health practitioners and nurses, often involve other staff (eg allied health assistants and care workers) and family to implement aspects of the program, and largely occur in the community setting. The involvement of GPs, although encouraged in government and service program guidelines, tends to be variable.

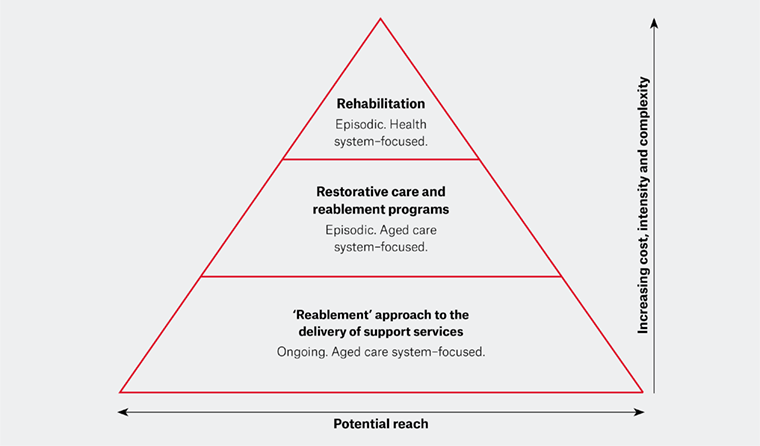

While generally less complex and less costly than rehabilitation, the reach of reablement and restorative care programs is potentially broader, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Rehabilitation, reablement and restorative care: Potential reach, cost, intensity and complexity

For greatest efficacy, programs offering reablement or restorative care should draw on evidenced-based interventions and be delivered in a ‘dose’ sufficient to achieve a benefit. A range of effective interventions could form components of such programs, for example, multicomponent exercise interventions,7 progressive resistance training,8 occupational therapy interventions,9 interventions targeting people with frailty10 and interventions that might positively affect function in people living with dementia.11

Note that the term reablement is also used to describe a way in which ongoing community support services (such as personal care and home care) are delivered to help people maintain their ability to perform daily tasks.4 In this context, allied health practitioners are not usually involved. For example, a service that takes a person shopping (because they are unable to manage public transport) may be described as reabling if it allows them to choose their own groceries, continue cooking and maintain extended outdoor mobility. This type of service is described as ‘doing with’ someone (ie assisting with the aspect of a task they cannot do, thus allowing them to do the remainder of the task themselves) as opposed to ‘doing for’ them (ie delivering cooked meals, thus discouraging choice, cooking and mobility). Support services used in this way have broad reach (Figure 1).

While the intent of a rehabilitation program is primarily centred on the individual’s specific functional deficits, reablement and restorative care programs often have additional aims, such as to reduce the need for premature placement into residential care12 or to delay or reduce the need for community support services.13,14 This may also contain the costs of long-term care, though the supporting evidence remains limited. Reablement and restorative care programs can also address the broader social and psychological needs of older people through group-based programs and opportunities to reconnect with the community.14

All three terms, being ‘re-’ words, imply a return to a previous level of functioning. However, in progressive conditions (eg dementia), a satisfactory outcome may be the maintenance of, or slower rate of decline in, functional ability.11–15 Conversely, a new domain of functional ability may be attained, as opposed to re-gained; for example, the fostering of new creative skills following a participatory arts program.16

The government-funded programs within Australia that have a focus on functional ability are described in Table 1.

| Table 1. Nationally available reablement and restorative care programs for older people in Australia* |

| |

Transition Care Programme12 |

Short-Term Restorative Care Programme3 |

Commonwealth Home Support Programme4 and the Home Care Packages Program24 |

| Type |

|

|

- Mix of time-limited and ongoing

|

| Eligibility |

- Must follow a hospital admission

|

- The functional decline must not be linked to a recent hospital stay

|

- Eligibility not related to a hospital admission

|

| Target group |

- Older people at the conclusion of a hospital episode who require more time and support in a non-hospital environment to complete their restorative process, optimise their functional ability and finalise and access their longer-term care arrangements

|

- An early intervention program for older people that aims to reverse and/or slow functional decline and improve wellbeing; excludes older people already receiving residential care, an HCP or Transition Care

|

- CHSP: Entry-level community support services and some therapy services for older people who require assistance to remain living in their own homes

- HCPs: These sit between CHSP and residential care, providing a higher level of community support services

|

| Program description |

- Time-limited, goal-oriented and therapy-focused services

- Service packages include low intensity therapy (eg physiotherapy or occupational therapy), social work, personal care and nursing support

- Includes a case management component

- Programs are delivered in the community or in residential care

|

- Time-limited, goal-oriented and therapy-focused services

- Care team is multidisciplinary and comprises a minimum of three health professionals, including a medical practitioner (usually the person’s GP)

- Includes program coordination

- Delivery is usually in the community, but can include residential care

|

- CHSP: An emphasis on wellness and reablement is promoted; services include some allied health, nursing, social support and respite

- HCPs: Package recipients can access allied health and nursing if they choose (HCPs operate on a consumer-directed care basis)24

- Delivery is in the community

|

| Duration |

- Up to 12 weeks, with a six-week extension if needed

|

|

- CHSP/HCPs: Support services can be ongoing; allied health is usually episodic

|

Referral

|

- In-hospital referral to an ACAT25

|

- myagedcare portal25 (GP can refer)

|

- myagedcare portal25 (GP can refer)

|

| Assessment/approval |

- Eligibility determined by an ACAT during an in-patient hospital stay

|

- Eligibility determined by an ACAT

|

- CHSP: Eligibility determined by a Regional Assessment Service

- HCPs: Eligibility determined by an ACAT

|

| Funding |

- Jointly funded by the Australian Government and state and territory governments

|

- Funded by the Australian Government

|

- Funded by the Australian Government

|

| *Older people (usually those aged ≥65 years; or ≥50 years for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples) are eligible, as long as other assessment criteria are met. ACAT, Aged Care Assessment Team; CHSP, Commonwealth Home Support Programme; GP, general practitioner; HCP, Home Care Packages |

A function-focused approach in primary care

In ageing populations there is a high prevalence of multimorbidity, the main consequences of which include functional decline, diminished quality of life and frequent healthcare use.17 Loss of functional ability can profoundly affect an older person and is often what prompts them to seek healthcare. In those with already reduced functional reserve, significant functional decline can occur quite rapidly following relatively minor illness or injury.18 Healthcare models designed to manage acute or single-system disease can fail to meet the full range of needs of an older person.19

The availability of reablement and restorative care services in Australia gives GPs a greater opportunity to address functional decline in community-dwelling older people, and thus to address their needs more comprehensively. These services increase access to allied health beyond the five sessions available as part of chronic disease management,

20 and some programs do not require prior hospitalisation as the trigger for eligibility (Table 1).

Drawing from the discipline of rehabilitation medicine, we suggest the following as a function-focused approach in primary care. This approach looks holistically at the nature of, and contributors to, an older person’s functional decline, and then applies strategies to improve functional ability through maximising intrinsic capacity and using environmental modifiers when necessary and available. For GPs, this means looking beyond disease management, and for allied health professionals and other providers of reablement and restorative care, it means working closely with GPs so that optimal disease management is in place.

A systematic approach using eight steps is suggested (described more fully in Table 2). The eight steps are:

- clinical assessment and optimal disease management

- functional assessment looking at physical, mental and social domains

- collaborative goal setting, with goals that are meaningful to the person and achievable

- evidence-based, goal-oriented allied health and nursing therapeutic and lifestyle interventions, targeted at improving intrinsic capacity and functional ability

- the use of assistive technologies and/or environmental modifications to compensate for remaining deficits (often done concurrently with step 4)

- the provision of community support services to address persisting deficits in functional ability that affect daily living

- supporting the health and wellness needs of family carers, who help enable the older person to remain in the community

- the provision of alternative or supported accommodation when living at home remains unsafe or too difficult.

Steps 2 through 5 usually require the involvement of allied health colleagues, who are now more accessible through reablement and restorative care programs. Referral mechanisms, by program type, are described in Table 1.

Good communication between GPs and program providers ensures that the best use is made of reablement and restorative care services. Communication can be facilitated through multidisciplinary case conference Medicare Benefits Schedule items when eligibility criteria are met.21

| Table 2. A function-focused approach to the care of older people |

| |

Steps |

Description |

Practitioners involved |

| Step 1 |

Clinical assessment and optimal disease management |

Determine underlying medical causes for functional decline and institute optimal disease management, including medication review and management of pain. Good collaboration between GPs and specialty physicians may be required to address multimorbidity.17 |

GP and non-GP specialist medical colleagues |

| Step 2 |

Functional assessment |

Assessment across physical, mental and social domains. A thorough understanding of the person’s environment is also needed. This step generally requires input from allied health practitioners and is ideally multidisciplinary. Good communication between all practitioners will foster a shared understanding of the patient’s deficits, including the identification of additional factors affecting intrinsic capacity (eg deconditioning) and the expectations for functional gain from interventions. |

GP, allied health and nursing |

| Step 3 |

Collaborative goal setting |

Goals should be meaningful to the person and achievable, since favourable outcomes are more likely if patients are engaged (ie are active participants) and if they feel confident of achievement (ie have self-efficacy). To maximise wellbeing, goals should span the physical (eg meeting basic needs, being mobile), mental (eg learning, growing and making decisions) and social (eg building and maintaining relationships, contributing) domains of function.2 |

Allied health and nursing, with GP, older person and carer involvement |

| Step 4 |

Allied health and nursing therapeutic and lifestyle interventions |

The implementation of evidence-based, goal-oriented allied health and nursing therapeutic and lifestyle interventions targeted at improving intrinsic capacity and delivered in a ‘dose’ sufficient to achieve a benefit. Interventions may include various combinations of strength, balance and endurance training to aid physical function or reduce falls risk; retraining in specific activities of daily living tasks; and nutritional interventions. |

Allied health and nursing |

| Step 5 |

Assistive technology and environmental modifications |

Used to enhance functional ability in the case of persisting deficits in intrinsic capacity. Examples include a mobility aid for safer and extended mobility, or a tablet device to increase the size of newspaper text for visual impairment that cannot be corrected. |

Allied health and nursing |

| Step 6 |

Support services |

Persisting deficits in functional ability may require assistance from support services. Australia has a large array of services available through the Commonwealth Home Support Programme, Home Care Packages Program or the Department of Veterans Affairs.25 All services have eligibility and assessment requirements.25 Accessing government-funded aged care services is done via the myagedcare portal.25 Private-pay options also exist. |

Various providers of aged care support services |

| Step 7 |

Carer support |

It is essential to support the health and wellness needs of an older person’s carer, as carers enable older people to remain at home and engaged with their communities. Support may include day or overnight respite. Through education, carers can also be active participants in identifying the onset of functional decline and in supporting interventions to address it. |

GP, allied health and nursing, as well as providers of aged care support services |

| Step 8 |

Alternative accommodation |

May be required if living at home remains unsafe or too difficult. |

GP, Aged Care Assessment Team |

| GP, general practitioner |

Conclusion

The emergence of reablement and restorative care complementing rehabilitation is a welcome development in policy that should increase the access of older people to services that target the functional deficits that are important to them. While already available nationally, the Australian Government has flagged an increase in restorative care services over coming years.22 GPs are important to identify and refer older people likely to benefit, and they play an essential part in effective program delivery.

However, unlike rehabilitation programs in Australia,23 reablement and restorative care services are lacking when it comes to ongoing evaluation and benchmarking. To ensure that the most efficacious programs are being delivered, data are required on the nature of the interventions employed (to and by whom, type and ‘dose’) and the outcomes achieved. These data would provide greater program and provider transparency, and enable informed consumer choice and an assessment of cost–benefit.