Case

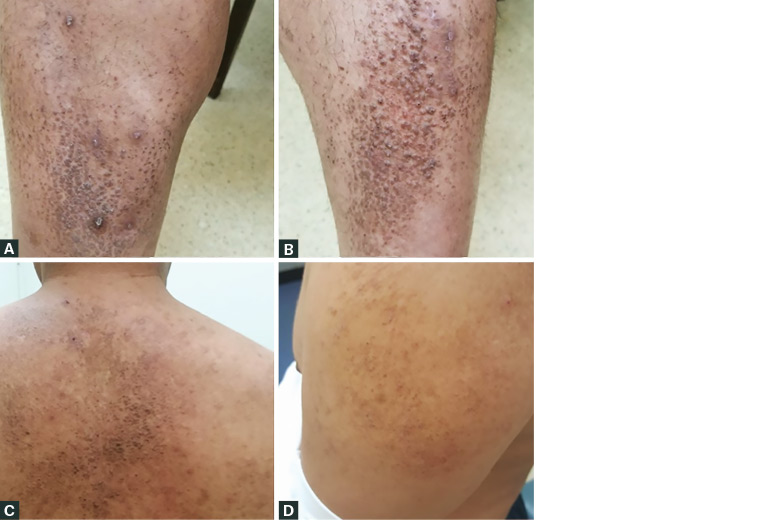

A man aged 47 years presented with a three-year history of intensely itchy legs following failed treatment with mild to mid-strength topical steroids elsewhere. The patient reported no other medical problems, and there was no family history of any skin disorder. Red-brown and red-grey papules were present on the anterior, antero-medial and antero-lateral skin of both legs (Figure 1). With time, some lesions became small firm nodules with adherent scale. His body mass index (BMI) was 29 kg/m2, and the systems examination was normal. A shave biopsy revealed lichen amyloidosis, (Figure 2). Full blood examination, urea, electolytes, creatinine, liver function test and urinalysis (protein) were normal.

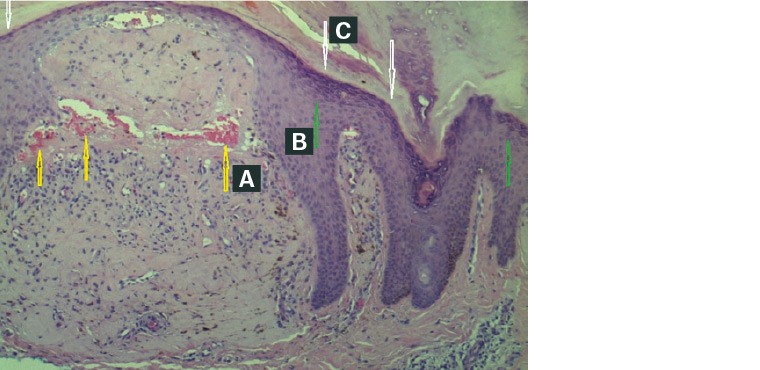

Figure 1. Lichen amyloidosis initial presentation and three months post-treatment

A. Left leg initial presentation; B. Right leg initial presentation; C. Left leg three months post-treatment; d. Right leg three months post-treatment

Figure 2. Lichen amyloidosis histology

A. Congo red stain in papillary dermis; B. Epidermal hyperplasia; C. Hyperkeratosis

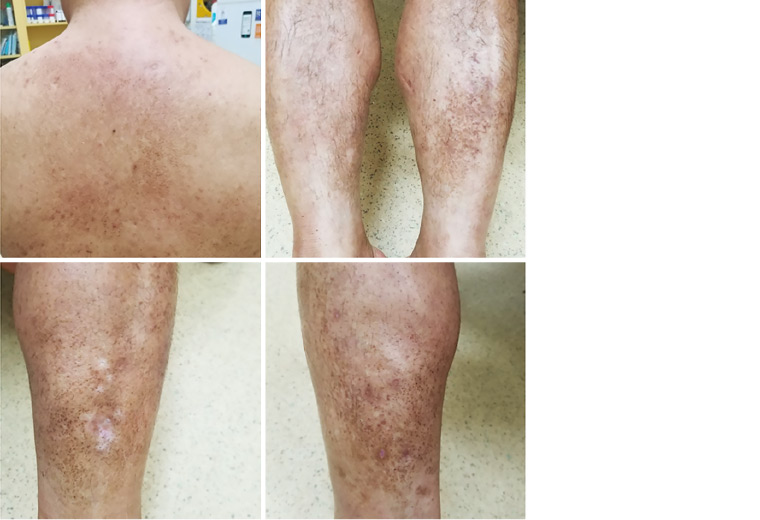

The patient was treated for three months with a combination of intralesional corticosteroid injection and topical application of compounded triamcinolone acetonide 0.02%, salicylate acid 5% and urea 10% in sorbolene (Figure 1). The injection involved 0.2–0.4 mL of triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL with dilution of plain 1% lignocaine or normal saline, injected per square centimetre of involved skin with a Luer Lock syringe. Topical applications, with occlusive dressings, were daily for four weeks, alternating days for four weeks, and then twice weekly. There was a marked clinical improvement and the patient ceased treatment. He presented 18 months later with recurrence on both legs, upper back and torso (Figure 3), and responded to similar treatment (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Lichen amyloidosis recurrence after 18 months

A, B. Recurrence on legs after 18 months; C. Progress to back; d. Progress to arm

Figure 4. Two months post-treatment of recurred lichen amyloidosis

The patient had occasional folliculitis treated with oral antibiotics. He also displayed depressive symptoms secondary to the cosmetic appearance of the eruption, which required psychological support.

Question 1

What are the classical clinical features of lichen amyloidosis?

Question 2

What is the aetiology of lichen amyloidosis?

Question 3

How is lichen amyloidosis treated?

Answer 1

Lichen amyloidosis is characterised by intensely pruritic, multiple raised red-brown and red-grey papules of 2–3 mm size. With time, some lesions become small firm nodules with adherent scale. The lesions usually start on the legs and may progress to the back, torso and arms.

A clinical ‘spot’ diagnosis is easily made in most situations, accompanied by a thorough history and examination to exclude any overlooked conditions. One study has suggested that dermoscopy is useful to identify characteristic features of central hubs (white or brown, surrounded by various configurations of hyperpigmentation) in lichen amyloidosis.1

A punch or deep shave biopsy can be performed when there is uncertainty, preferably including epidermis, dermis and fat in the specimen.

Owing to the infrequency of this condition, there are no valid studies of worldwide epidemiology. Lichen amyloidosis most commonly occurs in people with Fitzpatrick skin types 3 and 4. Lichen amyloidosis usually presents in the fifth and sixth decades of life but can present as early as the third decade.2,3

Lichen amyloidosis may be associated with atopic dermatitis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 and autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and thyroiditis.4–7

Answer 2

Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localised cutaneous amyloidosis (PLCA) of the skin. It is unrelated to systemic amyloidosis (ie involvement of internal organs). The aetiology of lichen amyloidosis is unclear; however, chronic irritation to the skin such as rubbing or scratching is a possible contributing factor.8,9

Lichen amyloidosis is more frequent than other types of PLCA such as macular amyloid, nodular amyloid and familial primary cutaneous amyloidosis.10

Answer 3

Unfortunately, standardised treatment guidelines have not been established because of a lack of randomised control trials.11 Treatment addresses the primary complaints of intense pruritus and the clinical appearance of the eruption. Long-term periodic follow-up is required as recurrence is common. General skincare measures such as using a soap-free wash, emollients/moisturisers and trimmed nails are important. Sedating antihistamines can help with disturbed sleep.

Depending on the extent and location of the lesions, specific management options for lichen amyloidosis can include:

- topical therapy10,12,13

- topical corticosteroids with an occlusive dressing to maximise efficacy (eg mometasone furoate 0.1%, betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%, triamcinolone acetonide 0.1%, methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1%)

- anti-pruritic creams (eg capsaicin, doxepin)

- keratolytic agents (eg salicylate acid, lactic acid, urea)

- dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO 10%), used intermittently14,15

- tacrolimus 0.1%

- intralesional corticosteroid injections

- oral acitretin or topical retinoids16–20

- phototherapy (pulse ultraviolet A, narrowband ultraviolet B) and laser (fractional carbon dioxide laser)12,13,21

- cryotherapy, cautery and curettage, and dermabrasion.

Referral to a dermatologist can also be considered.

Key points

- Lichen amyloidosis commonly presents as intensely itchy bumps on the legs, progressing to the back, torso and arms.

- Treatment depends on the extent and location of the lesions, and referral to a dermatologist may be necessary.

- Recurrence of lichen amyloidosis is common.