Superficial fungal infections are caused by dermatophytes in the Microsporum, Trichophyton and Epidermophyton genera.1 Dermatophytes live on keratin, which is found in skin, hair and nails. There is evidence that continuing migrations and mass tourism contribute to the changing epidemiological trends.2,3 Tinea infections are named according to the Latin term that designates the anatomic site of infection, such as tinea capitis (scalp), tinea corporis (body), tinea manuum (hand), tinea cruris (groin), tinea pedis (foot) and tinea unguium (nail).

Clinical manifestations

Tinea pedis

Tinea pedis, colloquially known as ‘athlete’s foot’, is the most common dermatophyte infection. Its prevalence increases with age;4 it is rare in children.5 Exposure to occlusive footwear, sweating and communal spaces are predisposing factors of tinea pedis.6 The interdigital subtype is the most common form of tinea pedis, which manifests as maceration or scales between toes (Figure 1).7 Another subtype is the chronic hyperkeratotic (moccasin-type) tinea pedis, which is characterised by chronic plantar erythema with scaling involving the lateral and plantar surfaces of the foot (Figure 2). The dorsal surface is usually spared in this subtype. A less frequent presentation of tinea pedis is the vesiculobullous or inflammatory form, which may sometimes be difficult to clinically distinguish from pompholyx eczema.8 Recurrent tinea pedis may be due to a reservoir of untreated tinea in the nails.

Figure 1. Interdigital tinea pedis: Erosion and scales of the subdigital and interdigital skin of the foot

Figure 2. Moccasin-type or chronic hyperkeratotic tinea pedis: Erythema and hyperkeratosis of the plantar/lateral aspects of the foot; consider oral therapy for these severe cases

Figure 2. Moccasin-type or chronic hyperkeratotic tinea pedis: Erythema and hyperkeratosis of the plantar/lateral aspects of the foot; consider oral therapy for these severe cases

Tinea unguium (onychomycosis)

Tinea unguium, also known as onychomycosis, is a dermatophyte infection of the nails. Onychomycosis is very common in the elderly with a prevalence of up to 50% in people aged over 70 years.9 Nearly half of patients with toenail onychomycosis were found to have concomitant fungal skin infections, most commonly tinea pedis.7 The most common clinical subtype is the distal lateral subungual onychomycosis that appears as yellowish or brownish discolouration associated with onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis (Figure 3). The other common subtype is the white superficial onychomycosis, which has the appearance of white spots on the nail plate that can involve the entire nail if not treated. Onychomycosis has many mimics (Table 1), so it is important to establish a mycological diagnosis before commencing therapy. Individuals with underlying nail disease are at increased risk of concomitant onychomycosis. Immunocompromised and diabetic hosts are not only at a greater risk of onychomycosis but are also more susceptible to the bacterial complications of onychomycosis, such as cellulitis.

Figure 3. Distal lateral subungual onychomycosis: The most common subtype of onychomycosis

| Table 1. Differential diagnosis of onychomycosis33–37 |

| Differential diagnosis |

Clinical features |

| Nail psoriasis |

- Shares many common clinical and histopathological features with onychomycosis

- Fingernails are usually more affected by psoriasis than tinea

- Nail pitting is the most common sign of nail psoriasis and rare in onychomycosis

- Nail bed ‘oil drops’: pink discolouration in the nailbed due to nailbed inflammation

- Other psoriatic skin changes

- Family history of psoriasis

- Can coexist with onychomycosis in 20% of people

with psoriasis

|

| Lichen planus |

- Typically affects several or most nails

- Other cutaneous features of lichen planus

- Pterygium unguis: Scarring between nail matrix and proximal nailfold

- Nail plate thinning and longitudinal ridging

|

| Yellow nail syndrome |

- Association with bronchiectasis, chronic sinusitis and lymphoedema

|

| Traumatic onychodystrophy |

- Usually only single nail affected

- Distal onycholysis

|

| Alopecia areata |

- Red-spotted lunula

- Regularly distributed nail pitting

|

| Age-related nail dystrophies |

- Onychauxis and onychoclavus can be clinically identical to onychomycosis

|

Tinea capitis

Tinea capitis is a dermatophyte infection of the scalp and hair and it predominantly occurs in pre-pubertal children.10 The three main clinical presentations of tinea capitis are scaly patches with alopecia, alopecia with black dots at the follicular opening and diffuse scalp scaling with subtle hair loss. A severe form of tinea capitis is referred to as ‘kerion’, which is characterised by a tender plaque with pustules and crusting.11 If untreated, kerion may cause permanent scarring and alopecia. Cervical lymphadenopathy is a common associated finding in patients with tinea capitis.12

Tinea corporis and tinea cruris

Tinea corporis, commonly known as ringworm, refers to a dermatophyte infection on the skin of sites other than face, hands, feet or groin. Tinea cruris is also known as ‘jock itch’ and occurs in the groin fold and is more frequent in adult men.13 Tinea corporis most commonly occurs in children and young adults. Tinea corporis (Figure 4) and tinea cruris (Figure 5) classically present as annular plaques with central clearing and leading scale. The lesions may be single or multiple and of varying sizes, which may coalesce. Pustules or vesicles can sometimes occur at the active edge. Although tinea infection is common, it is important to consider many other causes of an annular rash as described in Table 2.

Figure 4. Tinea corporis of the neck: Classic annular erythematous plaque with leading scale

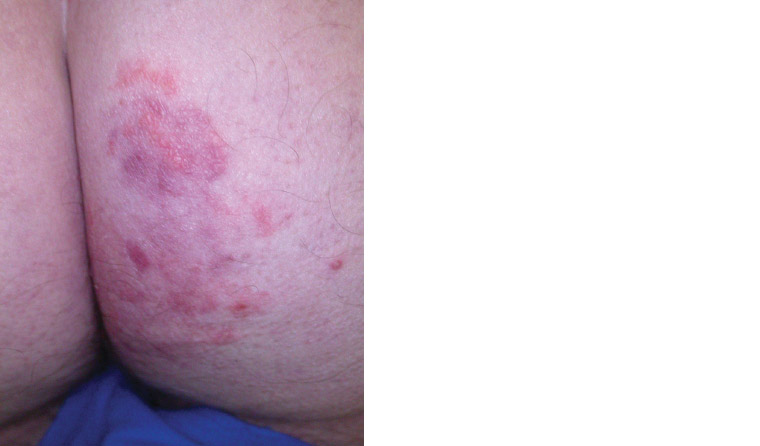

Figure 5. Tinea cruris: Annular plaque over the groin fold

Figure 5. Tinea cruris: Annular plaque over the groin fold

| Table 2. Think beyond tinea: Differential diagnosis of tinea corporis (annular rash)32 |

| Differential diagnosis |

Clinical features |

| Discoid eczema (nummular) |

- Less likely to have central clearing (but can occur)

- More confluent scales

|

| Annular psoriasis |

- Silvery scale

- Nail pitting

- Family history of psoriasis

|

| Pityriasis rosea |

- Herald patch progressing to generalised rash

|

| Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus |

- More common in females

- Photosensitive areas

|

| Erythema annulare centrifugum |

- Trailing scale rather than leading scale in tinea

|

Tinea incognito

Tinea incognito is a term for a tinea infection that has been misdiagnosed and inappropriately treated with a topical corticosteroid or other immunosuppressive agents. The clinical features may become masked with attenuated scale and erythema, as well as a less well-defined border (Figure 6). The infection may also be exacerbated as the dermatophytes invade the dermis or subcutaneous tissue causing deep-seated folliculitis, also referred to as Majocchi’s granuloma.13

Figure 6. Tinea incognito: Loss of characteristic tinea appearance due to application of topical corticosteroid

Practical approach to diagnosis

A diagnosis of tinea infection may be suspected on the basis of clinical history and examination. Since many conditions can mimic tinea infections, it is recommended that investigations are performed to confirm the diagnosis. Although minor localised infections may be treated with empirical topical therapy, testing should be performed prior to commencing systemic therapy. Without the diagnostic confirmation, prescribers may not know when to stop the therapy.

In recurrent cases of tinea, it is essential to identify any potential reservoir for dermatophytosis. Toenails are a common reservoir for tinea and can result in recurrent tinea pedis as well as transmission by autoinoculation to other body parts, such as the hand and groin.14,15 As it is common for dermatophytes to concurrently affect more than one body part at the same time, a full skin examination should be performed to determine the extent of involvement and potential reservoir. In addition, animals may also be reservoirs. Microsporum canis is the most common dermatophyte isolate in tinea capitis, with cats and dogs recognised as important natural hosts.16 In these cases, animals should be tested and treated until mycological cure, to prevent reinfection in humans.

Diagnostic tests

Tinea infection can be diagnosed using fungal microscopy and culture, which allows for fungal speciation and viability assessment. Fungal microscopy of skin scrapings and nail clippings is performed on KOH (potassium hydroxide) and can be rapid. Fungal culture can take up to four to six weeks and but has a false-negative rate of at least 30% for nail samples.17 Repeat culture should be performed if there is a high index of clinical suspicion.

Advice on specimen collection

- Prior topical antifungal therapy may lead to false-negative culture results.

- Topical corticosteroid cream generally does not affect the isolation of dermatophytes but it can make it difficult to collect sufficient specimen. The cream should be wiped off prior to scraping.

- Each site needs to be collected in separately labelled containers to allow correct identification of the infective sites.

- Collect as much specimen as possible to maximise the yield.

- For skin scrapings:

- Use a scalpel blade, held at an angle.

- Always sample from the active leading edge of the lesion. Fungi are rarely identified from the interdigital macerated samples or the centre of the lesion. The moist interdigital areas of the feet are usually colonised with concomitant bacterial isolates, such as beta-haemolytic streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.18

- For nail clippings/scrapings:

- Use a nail clipper to clip the infected portion of the nail plate.

- In addition to the nail plate sample, collect as much subungual debris and as far proximally as is painless using a curette or scalpel blade.

- For a hair specimen:

- Use forceps or a brush to collect infected hair. Ensure to collect the hair root and scrape the area using a scalpel blade. Infected hairs usually come out easily.

- For small children, an alternative method is to use a sterile moistened cotton swab, which has been shown to be an equally reliable and atraumatic technique.19

Treatment modalities

The mode of treatment depends on the extent and location of the tinea infection. General tips for the management of tinea infection are listed in Box 1. Systemic therapy with oral terbinafine and azoles is summarised in Table 3.

| Box 1. Tips for tinea management20,42 |

- Examination of the skin and nails should be performed for all patients with tinea infection to identify the extent of involvement and potential reservoirs for dermatophytes.

- Topical treatments are usually ineffective against onychomycosis.

- Most nails still look abnormal after effective therapy because new nails take nine to 12 months to grow.

- Two simple methods to monitor the effect of onychomycosis therapy: 1) photographic monitoring, 2) marking the nail using a scalpel at the proximal end of the dystrophy. As the nail grows out, if the nail abnormality remains distal to the mark then no further therapy is required. Consider referral to an expert if therapy fails.

- Topical antifungal shampoos for tinea capitis can reduce the risk of fungal transmission to others but are ineffective in treating the infection.

|

| Table 3. Head-to-head comparison of oral terbinafine versus azoles in onychomycosis treatment20,23,24,38–41 |

| |

Terbinafine |

Azoles (fluconazole and itraconazole) |

| Recommended line of therapy |

|

|

| Dosage |

- Adult: 250 mg daily

- Child <20 kg: 62.5 mg daily

- Child 20–40 kg: 125 mg daily

- Duration: Six weeks for fingernails, 12 weeks for toenails

|

- Both itraconazole pulse and continuous therapy have

similar efficacy

- Pulsed itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for one week per month for two months (fingernails) and three months (toenails)

- Continuous itraconazole 200 mg daily for six weeks (fingernails) and 12 weeks (toenails)

- Fluconazole

- Fluconazole 150–300 mg once weekly for 12–24 weeks (fingernails) and 24–52 weeks (toenails)

|

Recurrence rate (follow-up

10–13 months) |

|

|

| Adverse effects |

- Gastrointestinal upset, rash, headache, myalgia

|

- Gastrointestinal upset, diarrhoea, rash, abdominal pain, hypokalaemia

- More drug interactions than terbinafine due to its inhibition on multiple cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes

|

| Recommended monitoring |

- Routine interval blood monitoring may be unnecessary in healthy adults and children without underlying hepatic or haematological conditions

|

- Continuous itraconazole: Baseline liver function test (LFT) and regular LFT monitoring every four to six weeks

- Pulsed itraconazole: none recommended

- Fluconazole: Baseline LFT and full blood examination; no repeat test required for once weekly therapy

|

| Precautions |

- Psoriasis and lupus may be exacerbated by terbinafine

- Contraindicated in severe hepatic disease

- Dose adjustment required if

CrCl <50 mL/min

|

- Dose adjustment may be required in renal impairment

- Avoid in severe hepatic disease

- Fluconazole can cause prolonged QT – correct the risk factors and use with caution

- Itraconazole is relatively contraindicated in congestive failure

- Itraconazole is also poorly absorbed when used with proton pump inhibitors

|

| Pregnancy categorisation |

|

|

- Itraconazole: Category B3

|

| Breastfeeding compatibility |

|

- Fluconazole: compatible; may cause diarrhoea in infant

|

- Itraconazole: avoid, insufficient data

|

Topical antifungal therapy

Most cases of tinea corporis, tinea cruris and tinea pedis are amenable to topical therapy. Recommended first-line topical therapy is terbinafine 1% cream once or twice daily for one to two weeks.20

In cases of onychomycosis with contraindication to systemic therapy, nine to 12 months of ciclopirox 8% nail lacquer once daily or amorolfine 5% nail lacquer once daily with debridement of hyperkeratotic nails can be offered but has low mycological cure rates of 29–36%21 and 38%,22 respectively.

Oral antifungal therapy

Oral therapy should be considered in the following scenarios:

- onychomycosis

- tinea capitis

- extensive tinea on the skin

- failed topical treatment

- immunocompromised patients.

Recommended first-line oral therapy for terbinafine 250 mg once daily for adults.20 Refer to Table 3 for paediatric dosing. Terbinafine is generally safe for use in healthy patients without the need for interval blood monitoring.23 However, it is contraindicated for patients with severe liver impairment and dose reduction is required for patients with moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease (CrCl <50 mL/min).20

The duration of oral therapy depends on the site:

- scalp: four weeks

- fingernails: six weeks

- toenails: 12 weeks (longer duration therapy is required because of diminished blood supply in the area, especially in the elderly)

- other than scalp and nails: two weeks.

A 2017 Cochrane review24 showed that terbinafine is superior to fluconazole and itraconazole for both clinical and mycological cure of onychomycosis (Table 3). There was also no difference in the rates of recurrence and adverse events.

Griseofulvin for six to eight weeks (paediatric dosing: 10 mg/kg up to 500 mg) is first-line therapy for tinea capitis caused by Microsporum infections.20 In contrast, griseofulvin is recommended as third-line therapy for tinea corporis because it is less effective than terbinafine and azoles for this indication.20 Griseofulvin is generally not recommended for onychomycosis as it has a longer treatment duration, higher rate of adverse events and is not more effective than terbinafine and azoles.24 Griseofulvin dosages vary depending on its indications: 500 mg once daily is recommended for tinea capitis, tinea corporis and tinea cruris; 1 g once daily is recommended for tinea pedis and onychomycosis.25

Laser therapy

The cure rates for laser therapy in onychomycosis are significantly lower than those for topical and oral therapies.26,27 Given its limited efficacy and high cost, laser therapy cannot be recommended as first-line treatment for onychomycosis.28

Prevention of recurrence

After therapy for onychomycosis, there may be a recurrence or reinfection rate of up to 25%.29,30 Patients should be advised to address modifiable risk factors for prevention of tinea infection, including avoiding sharing hairbrushes, clothes or shoes; avoiding walking barefoot around public showers and pools; and regularly alternating footwear and changing socks.

Following a cure, topical antifungal therapy (ciclopirox, amorolfine, bifonazole, terbinafine) can be applied weekly as prophylaxis. This method has been shown to significantly lower the recurrence rate in a retrospective study.31 The optimal duration of prophylaxis is unclear and may be indefinite.

Conclusion

Tinea is a common infection in the general community. It is a diagnosis that is frequently missed unless we think of it and test for it. Prompt recognition and management of tinea infection help reduce morbidity and its associated complications, as well as reducing the chance of transmission. The location and severity of tinea infection determine the empirical treatment modality and duration. As there are many mimics of tinea, clinicians should not prescribe oral antifungal therapy without a confirmed diagnosis.