Although glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common primary brain tumour, it has an incidence of only 6.8 per 100,000. As a result, most general practitioners (GPs) will care for very few patients with this condition, and low-grade tumours are even less common.1 However, the devastating functional and social ramifications mean GBM confers a disproportionate burden to patients and GPs. The family doctor has an essential role in surveillance, support and coordination of care. Despite improvements in surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the prognosis remains poor for most patients with high-grade gliomas.

Presentation and initial investigation

Brain tumours present a significant diagnostic challenge for primary care physicians because early symptoms are non-specific. A recent large observational study identified headache as the most sensitive symptom but found that only two in 1000 patients with headache had a brain tumour. Similarly, only 1.6% of patients with adult-onset seizures have a tumour.2 Combinations of symptoms are more sensitive – particularly headache, cognitive problems and weakness – but still have a positive predictive value of under 10% (ie only one in 10 patients with headache and cognitive problems or headache and weakness will have a tumour). Observing temporal trends in symptoms and identifying cognitive issues through collateral history or simple testing may be the best way to identify patients with a tumour.2 By the time the patient develops classic symptoms of raised intracranial pressure and morning headache and vomiting, with or without neurological deficit, the situation is an emergency.

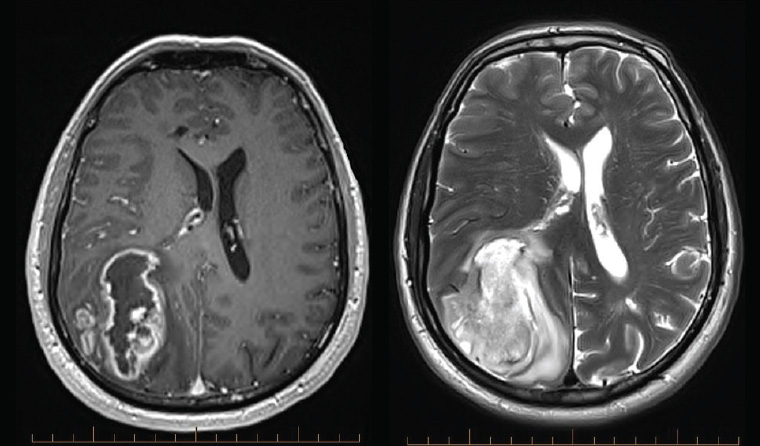

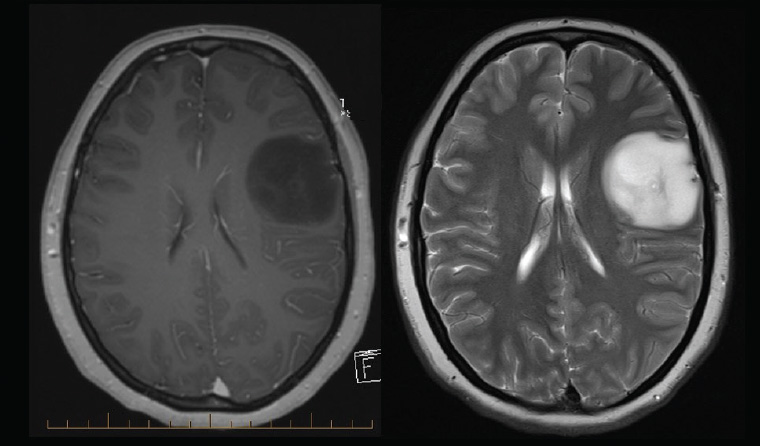

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is the appropriate initial investigation to diagnose or exclude an intracranial lesion. The imaging appearance of GBM is often very characteristic, showing peripheral enhancement around a region of central necrosis with variable degrees of surrounding oedema (Figure 1). This is concerning because the differential diagnosis is metastatic cancer or abscess. Low-grade gliomas appear hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 without the necrotic centre or enhancement (Figure 2). Newer imaging modalities such as positron-emission tomography (PET), MRI spectroscopy and perfusion imaging show promise but do not yet have the sensitivity or specificity to change usual management.3,4 Despite this, high uptake areas on fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET (18F-fluorodeoxy-glucose) or amino acid-based PET (eg 11C-methyl-methionine [11C-MET], 18F-fluorophenylalanine [18F-DOPA] or 18F-fluoroethyl-l-tyrosine [18F-FET]) may be used to guide biopsy or trigger surgery in a tumour otherwise thought to be low grade.4

Figure 1. Magnetic resonance imaging showing a typical glioblastoma with central necrosis and peripheral enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging (left), and surrounding oedema and midline shift on T2-weighted imaging (right)

Figure 2. Typical low-grade glioma with minimal mass effect, absence of enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (left), with little surrounding oedema on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (right). The imaging is consistent with numerous diagnoses including astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma, but this case is a World Health Organization grade II diffuse astrocytoma.

Initial management

On diagnosis of a probable brain tumour, the first challenge is breaking the bad news to the patient, keeping in mind that the diagnosis is not certain until histology is obtained. Symptoms of mass effect may be improved using dexamethasone, especially if there is associated cerebral oedema. A typical starting dose is 4 mg stat then daily in the morning. Anticonvulsants are indicated for seizures but not recommended for prophylaxis.1

Urgent neurosurgical review is required for patients with symptoms or signs of raised intracranial pressure, midline shift, hydrocephalus or neurological deficit, and these patients should be referred to an emergency department. Those with a long duration of symptoms and characteristic low-grade or small tumours on MRI may be reviewed as outpatients but should be discussed with a neurosurgeon or neurosurgical registrar.

Surgery

Surgery plays an important part in determining the pathological diagnosis and relieving symptoms. It may improve the efficacy of adjuvant therapy. Both debulking and complete resection of enhancing tumour are associated with extended survival when compared with biopsy alone, but it is not certain whether this association is causative or related to associated tumour and patient factors.5 The benefit of debulking has been confirmed in patients aged >65 years with GBM, and many elderly patients will be considered appropriate for craniotomy.6 Some elderly patients may prefer not to undergo cancer therapy; in this case, supportive palliative care should always be offered as an alternative, particularly for those with poor performance status or multiple comorbidities who benefit least from treatment.

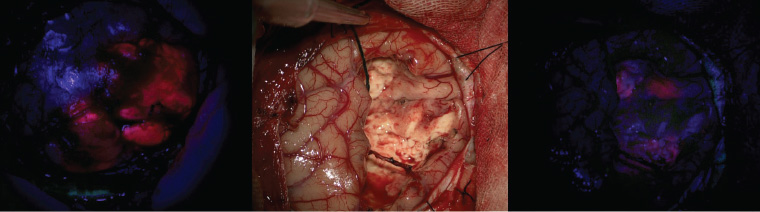

Surgical safety and efficacy are continually improving with modern technology. Fluorescence guidance with 5-aminolevulinic acid (Figure 3) has been shown to improve the extent of resection of high-grade glioma.7 For patients with a tumour near eloquent areas, awake craniotomy with intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring can be used to improve safety.5 Early postoperative MRI is essential to assess residual enhancing tumour and plan radiotherapy. Patients can expect to stay in hospital for approximately five days after an uncomplicated craniotomy, and most need at least six weeks off work.

Figure 3. Intraoperative imaging of fluorescence-guided surgery using 5-aminolevulinic acid. On opening the skull, the tumour can be seen fluorescing pink (left). After tumour resection, under conventional white light microscopy the surgical cavity has no apparent tumour (centre), but further tumour is visible fluorescing under blue light (right) and can be resected.

Diagnosis and molecular advances

Classification of tumours of the central nervous system now requires molecular analysis for characteristic mutations in addition to phenotypic assessment.8 The most important distinction is between gliomas with and without mutations in one of two genes for isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH). Phenotypically, high-grade gliomas without IDH mutation (IDH wild type) are the most aggressive and correspond to classic GBM. Tumours with the same histological features (ie pleomorphism, necrosis and endothelial proliferation) associated with IDH mutation show a better prognosis and overlap substantially with what was previously designated ‘secondary GBM’.8 Common IDH mutations can be shown on immunohistochemical staining; however, for younger patients or those with other (molecular) features suggestive of IDH mutation, genetic sequencing should be performed if the immunohistochemistry is negative.

The second major division is that in tumours with IDH mutation, co-deletion of chromosome arms 1p and 19q designates oligodendroglioma. IDH mutated/1p19q co-deleted (ie oligodendroglial) tumours have the best prognosis and the best response to treatment.9

Another important molecular marker is methylation of the promotor for the O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) gene, which is predictive for response to alkylating chemotherapy.9

The recent explosion in molecular data about primary brain tumours has identified numerous other mutations, such as the BRAF V600E mutation in epithelioid GBM and the H3-K27M mutation in diffuse midline glioma, which may be actionable targets for future treatments.8

Concurrent chemoradiation and adjuvant chemotherapy for glioblastoma

The current recommended treatment for GBM is based on the protocol of Stupp et al.1,9 This involves daily temozolomide, an oral alkylating agent, during radiotherapy (60 Gy in 30 fractions over six weeks), followed by six months of temozolomide for five days in 28 days. For older patients, hypofractionated radiotherapy (40 Gy in 15 fractions) has similar efficacy and may be given with or without temozolomide10–12 to reduce treatment time and burden. The target volume includes a 1–2 cm margin around the tumour treated by conformal radiotherapy to avoid vulnerable structures.9,13 Alopecia in the irradiated area, local skin reaction and fatigue that persists beyond radiotherapy are common side effects. Raised intracranial pressure causing headache, nausea and vomiting is possible and can be improved using dexamethasone.

For patients with poor performance status who are aged >70 years and are likely not to tolerate concurrent chemoradiation, temozolomide alone provides similar benefit to radiation alone and may be an appropriate alternative, especially for patients with MGMT promotor methylation.11,12

Temozolomide chemotherapy is usually very well tolerated. The most common adverse reactions are mild-to-moderate nausea and vomiting, transient myelosuppression with thrombocytopenia or neutropenia (~20%), and fatigue that may develop over months.14 Prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii (previously P. carinii) pneumonia is recommended for patients who continue to take ≥4 mg of dexamethasone during temozolomide treatment.1,14

Treatment for astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas

The ideal treatment for lower-grade astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas (IDH mutated, World Health Organization [WHO] grade II and III) is hotly debated. Patients with a growing, unresectable tumour or uncontrolled seizures should have upfront treatment usually starting with six weeks of radiotherapy (54 Gy).9,15 For other patients, although a significant survival benefit is conferred by radiotherapy and chemotherapy, it is not known whether treatment is better early, as soon as the diagnosis is made, or delayed as long as possible.15–17 The best chemotherapeutic regimen is also unclear. Procarbazine/lomustine/vincristine (PCV) is proven to be effective, particularly for oligodendroglial tumours, but has serious potential side effects including peripheral neuropathy. More recently, temozolomide has been used, supported by retrospective data and the Concurrent and Adjuvant Temozolomide Chemotherapy in Non-1p/19q Deleted Anaplastic Glioma (CATNON) trial for anaplastic (WHO III) astrocytomas.15,17,18 Patients with these tumours should be managed by subspecialist multidisciplinary neuro-oncology teams to make individualised, patient-centred treatment decisions. Ultimately, the choice of timing and modality of treatment will be determined by patient preferences and local practice.

Quality of life and general practice management within the community

The incurable nature of GBM means quality of life during treatment is of the utmost importance. In addition to focal neurological deficits and fatigue – which may result from the tumour, surgery and radiotherapy – many patients have insomnia, cognitive problems and psychological issues relating to the diagnosis. Rehabilitation has been shown to be as effective in restoring function for patients with brain tumour as it is in patients following stroke.1,19 Those with symptoms or functional disability from neurological or cognitive impairment may benefit from referral to appropriate allied health services, including occupational therapy, speech pathology and neuropsychology, whether or not the patient has had surgery.

Ongoing steroids may be required to manage symptoms and radiotherapy-related oedema but should be weaned as soon as possible in consultation with an oncologist. Patients should be monitored for side effects, including diabetes, infections and skin lesions, and weaning should be carried out gradually to avoid symptomatic adrenal insufficiency.14 First-line anticonvulsants for treatment of seizures include sodium valproate for generalised seizures and carbamazepine for focal events. In patients who have not had seizures, anticonvulsants can be stopped after surgery.1,9

Depressive symptoms are common and may be addressed by psychosocial support, cognitive behavioural therapy or mindfulness training. A referral to a psychologist may be helpful.9,20 Continuing moderate regular exercise is beneficial, but support and direction from an exercise physiologist or physiotherapist may be necessary.21

Driving is proscribed for six months after supratentorial surgery,22 but seizures and cognitive or neurological deficits prevent many patients with glioma regaining their licence. If in doubt, an occupational therapy driving assessment is essential.

Psychosocial issues are particularly important for patients with low-grade glioma who may live for years or decades after diagnosis and are often younger, with dependent family and financial obligations. GPs can provide an important educational and supportive role as patients grapple with their responsibilities and self-identity in the face of the existential threat and possible impairment and personality change caused by a tumour. The family is also likely to benefit from counselling and support. Online resources (Table 1) and local Cancer Council support groups are often useful.

Management of recurrent tumour

Even with maximal therapy, GBM tumours almost inevitably return. Despite this, there is no standard of care for management of progression. Re-operation is useful to distinguish recurrence from treatment effect (pseudoprogression) and is associated with longer survival, but this may be due to selection bias. In some cases, re-irradiation is feasible. Second-line chemotherapy options include metronomic temozolomide (continuous daily instead of five days in 28) and lomustine.

Bevacizumab has recently been approved on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme for use in recurrent or progressive GBM. This monoclonal antibody targets vascular endothelial growth factor, a gene commonly overexpressed in GBM. Trial evidence to date suggests that bevacizumab restores the blood–brain barrier, reducing enhancement on MRI scans and reducing oedema, thereby improving symptoms. However, bevacizumab does not have cytotoxic effects that extend survival.9

Tumour treating fields are a novel treatment modality using alternating electrical fields applied to the head through electrodes worn for 18 hours per day.9 The mechanism for the supposed effect remains unclear; there is no blinded randomised controlled trial and it requires purchase of expensive disposables, causing scepticism among many neuro-oncologists.23 It is unlikely to be introduced to Australia in the foreseeable future.

Current research frontiers

Unlike trastuzumab for breast cancer, sunitinib for renal cancer and dabrafenib for melanoma, no targeted agents have yet been identified that improve survival in GBM. Research continues, with numerous Australian trials currently underway, including trials investigating agents active against EphA3 receptors (KB004), tubulin (ACT001) and transcription factors PAX-1 and NF-kB. Many guidelines recommend enrolment in a clinical trial as optimal care for glioma patients.1,9,24

Although the brain is relatively protected from systemic immune responses, there is laboratory and clinical evidence that immunotherapy may be harnessed against brain tumours by counteracting the tumour-induced immunosuppression (immunomodulation), sensitising immune cells to tumour antigens (tumour vaccines) or by in vitro expansion and reinfusion of anti-tumour immune cells (adoptive immunotherapy). The Australian NUTMEG trial is currently testing immunomodulation with the PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor nivolumimab in patients aged >65 years with unmethylated GBM, and more than a dozen similar trials are underway overseas. Tumour vaccines and adoptive immunotherapy have to date been unsuccessful, but this remains an active field of research.25

The use of modified viruses to activate the immune system against the tumour cells is also under investigation. In a Phase II dose-finding study of a recombinant non-pathogenic polio-rhinovirus chimera (PVSRIPO) infused into the brain by convection-enhanced delivery, 20% of patients remain alive and well three years after treatment for recurrent GBM.26 Similar but less spectacular results have been observed after trials of other viral treatments.26 This offers hope that oncolytic viral therapy may provide lasting benefit for at least some patients, although optimism should be tempered as many treatments that appear promising in Phase II trials have been ineffective in large randomised controlled Phase III trials.27

Prognosis

Patients vary in their desire to discuss prognosis, and statistical averages do not necessarily apply to a particular patient. The median survival of patients aged >65 years with GBM is under three months after biopsy alone,6 whereas for younger patients with compete resection of enhancement, median survival is nearly two years.5 This means half the patients may live longer than two years. Population data suggest the five-year survival for patients with GBM is approaching 10%, a significant improvement on earlier decades.28

Lower-grade gliomas have an even more variable prognosis because of the unpredictable progression to high-grade tumours. Median survival after radiation and PCV chemotherapy for diffuse WHO grade II astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas is >13 years.16

Palliative care

Referral to specialist palliative care services is valuable for patients with high-grade glioma as soon as the patient has needs that these services may address. Early referral enables relationships to be established and plans made before the terminal phase of the illness, and is associated with fewer unplanned hospital admissions and better symptom control.1,9 Terminal palliative care undertaken by GPs within the patient’s local community enables the best possible quality of life for patients with brain tumours during their final months.

Key points

- Management of patients with primary brain tumours is complex, so patients should be referred to a tertiary centre with subspecialist neuro-oncologists and a brain tumour multidisciplinary team.

- Recent advances in the molecular understanding of brain tumours have improved prognostication but not yet changed treatment significantly.

- Primary care physicians can ameliorate the burden of illness by managing the significant symptoms, psychosocial issues and supportive care needs encountered by patients with primary brain tumours.