Definitions of sexual assault are numerous. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ 2016 Personal Safety Survey, ‘sexual assault is an act of a sexual nature carried out against a person’s will through the use of physical force, intimidation or coercion, and includes any attempts to do this. This includes rape, attempted rape, aggravated sexual assault (assault with a weapon), indecent assault, penetration by objects, forced sexual activity that did not end in penetration and attempts to force a person into sexual activity. Incidents so defined would be an offence under state and territory criminal law’.1

There is no entirely satisfactory term available to describe a person who has been sexually assaulted. As this article is aimed at medical practitioners, the term ‘patient’ has been used; the term ‘victim’ has been used only when referring to legal or police procedures.

Both men and women experience sexual assault. However, the vast majority of presentations to most sexual assault services are women. For ease of reading, this article uses the female pronoun. However, it is important to acknowledge that anyone can experience sexual violence, and transgender and gender diverse Australians experience sexual violence at a rate approximately four times greater than the general population.2

Prevalence

In Australia, in 2016 an estimated 18% (1.7 million) of all women aged ≥18 years and 4.7% (428,000) of all men aged ≥18 years had experienced sexual assault since the age of 15 years. An estimated 1.6% (148,100) of all women aged ≥18 years and approximately 0.6% (57,200) of all men aged ≥18 years had experienced sexual assault in the past 12 months.1

This correlates well with other estimates of prevalence; however, all estimates of prevalence of sexual assault are problematic because of low reporting rates, variable definitions of assault and huge methodological differences between studies.3

Presentation

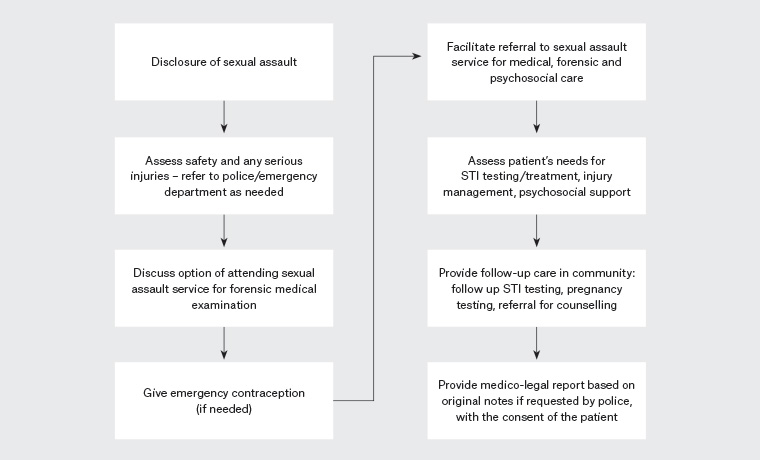

People who have experienced a sexual assault may present to primary care immediately with concerns related to injury, safety, sexually transmissible infections (STIs) and pregnancy, as well as psychological trauma. The steps for a general practitioner (GP) to take following a disclosure of sexual assault are outlined in Figure 1. Some may present to their GPs for follow-up after having accessed a specialised sexual assault service. However, many people do not immediately disclose a sexual assault, and many will never disclose this information unless it becomes relevant to their care.4

Figure 1. Flowchart to describe the options for care following a disclosure of sexual assault. Click here to enlarge

STI, sexually transmissible infection

History

The initial history should assess the safety of the patient (and, in some cases, her family) and the patient’s immediate needs. It is also crucial to determine the recency of the assault, as this informs the forensic options. Points to cover include the following.

- Injury. Most sexual assaults do not involve any major physical injury over and above the sexual assault. However, there are some specific injuries that, although uncommon, do appear to be linked to sexual assault and are potentially life threatening. These include strangulation, head injury or penetration with an object.5 Strangulation in the context of intimate partner violence is associated with an eight-fold increase in the risk of future fatality6 and also carries immediate health threats because of compromise of the airways and the great vessels. Any patient who has had pressure put on her neck during an assault should be asked about throat symptoms, difficulty breathing and neurological changes. Patients can be referred to an ear, nose and throat specialist or to the emergency department for evaluation.7

- Safety. Is the patient still at risk from the assailant, and does she have a safe place to go following any intervention? Hospital social workers and domestic violence services may be able to help with this. If the patient is willing to contact the police, an Apprehended Violence Order (AVO) against the assailant may be appropriate to put in place. This is a court order that prohibits the named offender from making contact with the victim; specific details of the contact will be spelled out in the order. Specific questions to assess immediate safety may include, ‘Are you safe to go home from here?’ and, ‘Is the offender still in contact with you?’ Some further information on safety assessment and safety planning in the context of domestic violence is detailed in the referral section of this article.

- Forensic examination. If the patient wants to undergo a forensic examination, this should occur once life-threatening injuries have been excluded and before other medical interventions are offered. The one exception to this is emergency contraception, which can be given prior to any forensic intervention if needed. It is entirely the patient’s decision whether she has a forensic examination; however, if it is done, the examination must take place within forensic timeframes. In general, a forensic examination must take place within seven days of the sexual assault, depending on the nature of the assault. The timeframes detailed in Table 1 are relevant to NSW, but each state and territory has a different set of guidelines, led by the local forensic laboratory. A forensic examination must be performed by a trained medical professional (doctor or nurse) within a designated facility. Specialist sexual assault services are located throughout the states and territories. Although there is variation between states in terms of how sexual assault services are structured, all Australian jurisdictions have provision for dedicated sexual assault services to offer direct access crisis medical, forensic and psychosocial care for patients.

| Table 1. Forensic timeframes for adults: Timeframes for collecting trace evidence following sexual assault (NSW Police recommendations)5 |

| Nature of assault |

Timeframe for collecting evidence |

| Licking |

12 hours |

| Indecent touching (including digital vaginal or anal penetration) |

12 hours |

| Penile penetration of the mouth |

24 hours |

| Penile penetration of the anus |

48 hours |

| Penile penetration of the vagina |

Up to five days |

If the patient accesses a forensic medical service, this service should be able to coordinate the patient’s immediate and ongoing medical and psychological needs and may only refer back to the GP as needed for follow-up. However, if the patient does not want to access a specialist service, the care outlined in this article should be considered.

Sexually transmissible infections

Many patients are concerned about the possibility of having contracted an STI through a sexual assault. However, there is little or no evidence that an assault places a patient at a higher risk of STIs than any other sexual exposure.8–10

Baseline STI testing may be carried out at the time of presentation and is often useful to diagnose pre-existing infection, including determination of a baseline hepatitis B immunity status. However, testing carried out within 10 days of the assault is unlikely to identify incident infection from the assault, and there is a theoretical risk of a false-positive result from offender semen. Any positive result will need to be followed up with appropriate contact tracing.

Ideally, follow-up tests for bacterial STIs (chlamydia and gonorrhoea) should be performed at 14 days post-exposure, or whenever the patient presents after 14 days; for syphilis and blood-borne viruses, testing should be performed at three months post-exposure.11

Management of symptomatic patients may also include testing for Mycoplasma genitalium, Trichomonas vaginalis, herpes simplex virus, bacterial vaginosis and Candida albicans, according to national guidelines.11 However, this testing is not usually performed for asymptomatic patients.

Patients should be given information regarding the possible signs and symptoms of infection and asked to re-present if symptoms occur; however, it is important to note that most infections are asymptomatic, so a lack of symptoms should not preclude patients from attending for follow-up.

Infection prophylaxis

The topic of ‘prophylaxis’ against STIs following sexual assault is a problematic one. Most research shows that infection due to sexual assault is low;10 however, STI prevalence among women attending sexual assault services is high as many come from a population with a high prevalence of STIs.9 Follow-up attendance following sexual assault is low (approximately 30%, increasing to 50% with active follow-up), leading to recommendations of ‘prophylaxis’ at the time of presentation.8 However, if no baseline testing is done, treatment of pre-existing infection with azithromycin ‘prophylaxis’ potentially results in patients not receiving a diagnosis, contact tracing, counselling or follow-up. Single-dose azithromycin, which is commonly used for prophylaxis, is also linked to M. genitalium resistance.11

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend comprehensive prophylactic treatment because of the low rate of follow-up.8 However, the UK British Association for Sexual Health and HIV guidelines state:9

The advantages of bacterial prophylaxis have to be weighed against the disadvantages. These include unnecessary treatment, reinforcing belief that there was a high risk of infection (which in itself may raise levels of anxiety) and missing out on partner notification, if the source of infection was someone other than the assailant, leading to the possibility of re-infection by a regular or known sexual partner.

The Australian STI guidelines offer no recommendation regarding prophylaxis.11 Therefore, the choice becomes that of the patient, and to a certain extent the practitioner, who may make a judgement regarding the likelihood of the patient attending follow-up, the patient’s anxiety relating to the possibility of having caught an STI and the acceptability of waiting to be screened.

If antibiotic prophylaxis is to be used, the medications listed in Table 2 are recommended. Baseline STI testing should be carried out when antibiotic prophylaxis is prescribed so that contact tracing and treatment can occur if a pre-existing infection is diagnosed.

| Table 2. Sexually transmissible infection prophylaxis |

| Suggested treatment |

Clinical consideration |

| Azithromycin 1 g stat |

- For chlamydia

- May also provide protection against incubating gonorrhoea and syphilis

|

| Ceftriaxone 500 mg IMI stat |

- For gonorrhoea

- Consider use in high-risk populations (MSM, patients or contacts from high-prevalence countries)

|

| Benzathine penicillin 1.8 g IMI stat |

- For syphilis

- Consider use in high-risk populations (MSM, patients or contacts from high-prevalence countries)

|

| Hepatitis B vaccination – course of three doses |

- Consider use in non-vaccinated patients

- If started within 14 days, offers some post-exposure prophylaxis as well as ongoing protection

|

| HIV post-exposure prophylaxis |

- For exposures that confer a high risk of HIV exposure

- Prescribe as per the Australian national guidelines for post-exposure prophylaxis after non-occupational exposure to HIV

|

| HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IMI, intramuscular injection; MSM, men who have sex with men; stat, immediately |

Hepatitis B vaccination should be offered to non-immune patients or patients unaware of their hepatitis B status at the same time as baseline testing. If started within 14 days, vaccination offers some post-exposure prophylaxis as well as ongoing protection. Use of immunoglobulin is rarely indicated.12

If indicated, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) post-exposure prophylaxis must commence within 72 hours of the sexual assault. It is recommended that the GP consult the national guidelines13 for post-exposure prophylaxis after non-occupational exposure to HIV or seek the advice of their local sexual health or infectious diseases specialist. HIV post-exposure prophylaxis starter packs are available from emergency departments. The choice of medications used for prophylaxis will depend on local policy.

Contraception and pregnancy

It is important that emergency contraception is offered to women following sexual assault if there is a risk of pregnancy from the assault. Women should be offered a choice of emergency contraception from the three methods available in Australia: levonorgestrel, ulipristal acetate and the copper intrauterine device (IUD). Although the copper IUD is the most effective method available, most women will usually choose oral emergency contraception as an IUD can be difficult to arrange, may be costly and involves a procedure, which may not be acceptable to the patient. Both methods of oral emergency contraception are available in Australia from pharmacies without a prescription. Levonorgestrel emergency contraception should be taken within 72 hours of the sexual assault, but it has some efficacy up to 96 hours. Ulipristal acetate is effective for up to 120 hours after the sexual assault. Both methods are generally well tolerated, but ulipristal acetate is contraindicated in women who have severe oral steroid–dependent asthma or severe liver impairment. Administration of a progesterone-containing method of contraception within five days of ulipristal acetate is not recommended.14

Women at risk of pregnancy should also be advised to have a pregnancy test at three weeks post-assault and, if appropriate, should be given advice about ongoing contraception.

If an assault results in an unwanted pregnancy and a termination, then rarely the products of conception may be used as evidence in a criminal proceeding. If this is the case, liaison will take place between police, forensic services and the termination provider.

Management of injuries

Although sexual assault is associated with physical injury in approximately 60% of cases,15 these injuries are often minor and are more likely to be general body injuries than genital injuries. General body injuries are usually related to the circumstances of the assault and may include bruising or abrasions (grazes) to the arms or legs. Certain physical assaults can cause injuries that are specific to that act and cause characteristic injuries; therefore, it is important that healthcare practitioners are alert to these signs. For example, strangulation may lead to bruising around the neck, petechiae in the palate and the conjunctiva and tenderness over the thyroid and cricoid cartilage.7 Petechiae, erythema and bruising on the palate may also result from forced oral penetration, so a clear history should be taken.15

Between 20% and 50% of people who experience sexual assault have any genital injury.15,16 Generally these injuries are not medically significant and heal rapidly. Often no injury is seen by the examining doctor. This may be because the sexual contact was of a nature that did not include penetration, penetration occurred without injury or minor injuries have healed by the time the patient is examined. The research literature to date does not support a particular injury, pattern of injury or finding that can distinguish between consenting and non-consenting sexual intercourse.16,17

Documentation

Clinical documentation following a disclosure of sexual assault should be clear and precise. Even if a patient does not initially want to pursue police action, there is no statute of limitations on reporting sexual assault (ie no time limit), and notes may be subpoenaed many years after the initial presentation. Notes should record an account of the patient’s version of events (if possible, in her own words) and documentation of any examination that was carried out and any injuries that were found. Injuries are classified as bruises, abrasions (superficial grazes or scratches), lacerations (deep wounds resulting from blunt trauma) or incised wounds. Usually only lacerations or incised wounds will require specific medical attention, but all injuries should be carefully documented.GP’s should only release this information to police with the patient’s consent unless compelled to do so by a court order.

A suggested approach to injury documentation is the S4, C3, ABCD approach:5

- site (measured in relation to anatomical landmarks)

- size

- shape

- surrounds (features of surrounding tissue, eg swelling)

- colour (eg purple or yellow in a bruise)

- course (direction of the injury in a tissue plane)

- contents (presence of debris)

- age (signs of healing)

- borders (contours and margins of injury)

- classification

- depth (estimate).

Mandatory reporting

‘Mandatory reporting’ is the term used to describe the legislative requirements of certain people to report suspected cases of child abuse and neglect. The laws differ across Australian jurisdictions in terms of both who has reporting duty and in what situations.18

Although the emphasis of mandatory reporting in all jurisdictions is an ongoing risk of harm, most require reporting of any sexual assault of a minor (ie a person aged <16 years in all Australian states and territories expect Tasmania and South Australia, where the age of consent is 17 years), with an option to report those at risk of harm who are over the age of 16 years.

Any mandatory reporting should be done with the full knowledge of the minor involved. Mature minors can consent to their own healthcare, and this must be provided, irrespective of any child protection report that is being made. Children also have the right to confidentiality of their medical records, so it is important that only the factors that put them at risk of harm are disclosed and only to those who require this information to provide an appropriate intervention.19

Psychological first aid and responding to disclosure

Most healthcare workers feel ill-equipped to respond to a disclosure of sexual violence. A good initial response to disclosure is one that makes the patient feel believed and her experience validated. Some useful phrases for a health practitioner to use might be, ‘I am glad you could tell me this’ or, ‘I am sorry that this happened to you’.

It is not useful to ‘debrief’ a patient. Unless required in order to provide medical or forensic care, it is not necessary to ask for intimate details of the assault. However, it is important to listen if a patient needs to talk about the assault.20

During a sexual assault, many people report a fear of death.21 This experience of a ‘life-threatening’ assault helps to explain the severity and widespread nature of psychological impact. Immediately following sexual assault, many people will experience some form of acute stress reaction. This is usually characterised by heightened anxiety and fear, and avoidance of places or people that may trigger memories of the attack. Many patients have very vivid recollections of the assault that they may experience as ‘flashbacks’ or ‘nightmares’. Sleep patterns are often disturbed, leading to worsening of mood disturbances. These short-term effects usually peak at approximately two weeks post-assault and then gradually improve over subsequent months.21

In most cases, people are assaulted by a current or previous partner or by someone known to them. This relationship between the patient and her assailant can have a marked impact on the patient’s ability to process the trauma and to disclose the assault. Patients may be afraid of the assailant, feel too ashamed to admit the assault to mutual friends and feel in some way responsible for the assault.21

Simple measures can be put in place to help patients deal with these normal reactions to trauma. Often the most important thing is warning patients to expect an acute stress reaction and reassuring them that they are likely to recover. GPs can help by planning strategies with their patients to help make the patient feel safe and able to deal with these unwelcome emotions as they arise.22 However, it is important to refer for specialist help when needed.

Safety planning

In the case of domestic violence, the response should include safety planning.6 This is an ongoing process that should be informed by the patient’s preferences and choices. Safety planning should include a discussion about how to stay safe while in a relationship with a violent partner and information regarding how to leave the relationship, if the patient wishes to do so. It is important to remember that patients are at highest risk of serious violence when leaving an abusive relationship as the perpetrator may escalate in response to the patient’s actions.

Things to consider as part of a safety plan for a patient affected by domestic violence include access to accommodation, transport, money and protection of children and other household members. Emergency numbers including local services should be given to any patient who is experiencing domestic violence.23

Referral

Specialist sexual assault services exist in all states and territories. However, the structure of the service may be different between jurisdictions. Sexual assault services provide not only crisis medical and forensic intervention but also immediate and ongoing psychological support for patients and their families. In some jurisdictions, medical, forensic and psychosocial support are delivered by a single service. In other jurisdictions, separate services work together to provide care, but all services can be accessed by a patient directly through a single point of contact. Refer to Table 3 for details of sexual assault services.

Relationships Australia and 1800RESPECT both offer national crisis telephone counselling and are a good point of contact for referral to local services. In addition, each state or territory has a victim services scheme. Services offered by these schemes may include financial assistance, information, practical support and counselling services.

Many patients who have experienced violence are able to access counselling through a private psychologist. Prior to referral, it is worth checking that the psychologist has experience working with trauma patients as it is a specialised area. Local sexual assault services may be able to direct patients to experienced counsellors.

Summary

Patients presenting following a sexual assault may have a host of medical and psychosocial needs. By addressing these in a sensitive and methodical way, a GP can assist their patient to start to take control of her recovery from sexual assault.

Key points

- Sexual assault is a common occurrence.

- The patient’s immediate safety and medical needs should take first priority following a sexual assault.

- Patient concerns about STIs, pregnancy and management of minor injury can usually be met in primary care.

- Referral to a specialist sexual assault service is needed for a forensic examination and should be considered for psychosocial support.