Teenage pregnancy is a global health issue that adversely affects birth outcomes and can lead to intergenerational cycles of poverty and ill-health. In all settings, teenage pregnancies are more likely to occur in communities affected by social and economic disadvantage.1 In Australia, as in many high-income countries, the incidence of births in women and girls aged under 20 years has been falling over the past decade, dropping from 18.4 per 1000 in 2008 to 9.5 per 1000 in 2018.2,3 While this overall decline is generally regarded as a welcome trend, the pathways leading to teenage parenthood are diverse, and not all pregnancies are unintended or unwanted.4 While pregnancy in the teenage years can have a transformative impact on changing unhealthy behaviours and relationships for some individuals,5 this is not universal.

The social and health implications of teenage pregnancies include increased exposure to domestic violence (which may be exacerbated by the pregnancy), mental health disorders, substance use, sexually transmissible infections (STIs), financial stress and homelessness. Importantly, an individual’s education and training can be disrupted by teenage pregnancy, with variable opportunity for resumption. While teenage mothers are often motivated to do the best for their babies and to continue to develop themselves as parents and into adult life,6 they may be particularly susceptible to breaches of their rights to healthcare and education.7 Primary and secondary care services need to be teenage friendly to optimise engagement of young women who choose to continue a pregnancy.8 Similarly, schools and training facilities can enhance continuity of education by supporting return to study, breastfeeding and affordable childcare.

Teenage fertility rates

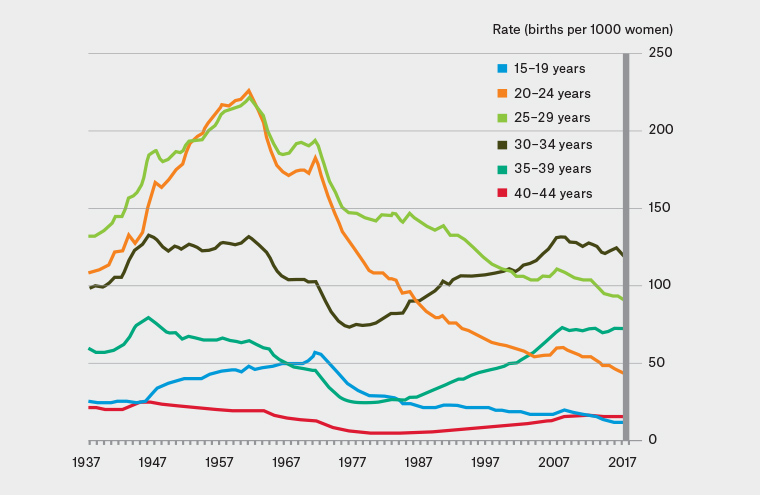

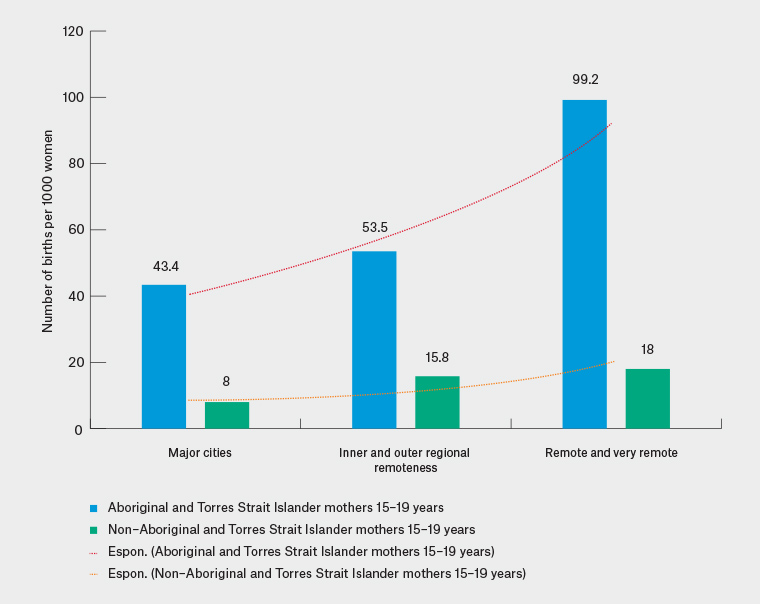

The teenage fertility rate is defined as the number of births per 1000 females aged 15–19 years (rates in girls under the age of 15 years are unstable because of low numbers and are not routinely collected).2,7 Rates of teenage fatherhood are not collected. National data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics show a decrease in teenage fertility rates over time (Figure 1), albeit with wide variation across different populations.9 While the rate in 2015 for non-Indigenous teenage girls was nine per 1000 teenagers, it was 53 per 1000 among teenagers who identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, with the rate highest in populations living in remote areas. Figure 2 shows that teenage pregnancy rates increased as remoteness increased, but this trend was more marked among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teenage girls when compared with non-Indigenous teenage girls.7

Figure 1. Age-specific fertility rates of selected age groups in Australia: 1937–20179

Reproduced with permission from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018)

Figure 2. Comparison of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non–Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fertility rates in 2015 by remoteness7

Reproduced with permission from the Australian Human Rights Commission 2017

Teenage abortion rates

In Australia, there are no national abortion statistics.10 Individual states that collect abortion data, including South Australia and Western Australia, report a declining trend in teenage abortion rates over the past five years.11,12 This parallels trends in the USA, which have been attributed to a combination of increasing access to effective methods of contraception, changing social norms and media influences.13

Factors associated with teenage pregnancy

In Australia, teenagers who become pregnant are more likely to be socioeconomically disadvantaged and to have experienced unstable housing arrangements and social welfare dependence, compared with teenagers who do not become pregnant.7 It is not uncommon for teenage pregnancy to occur in an intergenerational pattern in which the pregnant teenagers were born to young mothers who themselves experienced social, financial, medical, educational and employment difficulties.7,14 There is also an association between domestic violence and childhood sexual or physical abuse and teenage pregnancy.15 Nevertheless, qualitative studies have found that young women often show high levels of resilience and use any resources available to them to make their lives, and their children’s lives, happy and meaningful.16

Management of teenage pregnancy

Supporting the pregnant teenager

Providing quality healthcare to young women requires an understanding of the particular issues that are associated with teenage pregnancy and how to manage them (Box 1). In addition, programs supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women must be culturally appropriate, and Aboriginal controlled models of pregnancy care have been developed in various parts of the country to address this.17 General practitioners (GPs) play a part in recognising such vulnerability and improving the health literacy of these young people to support them in what is often a scary time, which can enhance the outcome for this pregnancy and for a future family. The principals of care, along with some key actions, are listed in Table 1.

| Box 1. Interventions and practice recommendations for the general practitioner to manage teenage pregnancy (adapted from Marino et al)62 |

Act to reduce the risk of unintended adolescent pregnancy

- In a sensitive and developmentally appropriate way, explore pregnancy intentions and contraceptive beliefs. Do this over time to accommodate changes in social situation.

- Encourage long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), which has been shown to be more reliable in this age group and should be the first-line recommendation.

- Check that young men and women know how to obtain and use condoms for sexually transmissible infection prevention.

- Check knowledge of emergency contraception.

|

When unintended adolescent pregnancy occurs

- Provide nonjudgemental support and counselling, including all options (check with local teaching hospital social work department or Public Health Networks for referral pathways).

- Screen for sexual abuse and exploitation, and be aware of the possibility of coercive relationships when the adolescent is pregnant to an older partner.

|

Antenatal care

- Refer to the local specialist service for teenage girls (or Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders if applicable/available).

- Recognise that teenagers may have less anatomical knowledge and will be less likely to understand what is happening to their bodies so may benefit from explanations at all stages.

- Assess nutritional adequacy.

- Use the local protocols for antenatal care, with special consideration of fetal growth.

- Screen for chlamydia as recommended in the first trimester; consider retesting later in pregnancy.

- Screen routinely for alcohol use, substance use, violence and mood disorders each trimester.

- Provide access to smoking cessation support.

- Teach about signs and symptoms of preterm labour and the importance of noting fetal movements.

- Discuss contraceptive options before delivery.

- Encourage and facilitate breastfeeding.

- Include fathers where possible.

|

Postpartum and beyond

- Encourage uptake of home visiting programs and the use of early childhood facilities and age-appropriate mothers’ groups.

- Encourage return to school, education or training and continuing healthy lifestyle changes made during pregnancy.

- Encourage continuity of breastfeeding, direct education on safe use of formula and provide ongoing advice about infant nutrition.

- Assess nutritional adequacy, particularly of breastfeeding mothers.

- Provide access to smoking cessation support.

|

| Table 1. Components of teenage-friendly healthcare |

| Principles |

Actions |

| Provide a welcoming environment |

Ensure waiting room and reception area are adolescent friendly, with magazines geared toward adolescents, as well as posters and brochures with targeted health messages. |

| Ensure services are easily accessible |

Ensure access to general practice care is inexpensive (or free via bulk billing). |

| Provide clarity regarding confidentiality and its limits |

Establish a trusting relationship by reassuring regularly about confidentiality. |

| Provide care that is respectful and inclusive |

Ensure care is supportive and not judgemental. Be a dependable authority whom teenage mothers can rely on.61 |

| Provide accessible information |

Be aware of current web- and application-based resources. |

| Use an empowering approach |

Ask how things are at home; seek information about difficulties. Focus on the ‘LIVES’ principles: Listen, Inquire, Validate, Enhance safety, and Support (LIVES). |

| Value the role of fathers |

Where possible, encourage involvement of the fathers in the pregnancy and birth. |

Exposure to sexually transmissible infections

STIs are an important consideration in teenage pregnancies because of the higher incidence of STIs among young women when compared with pregnant women over the age of 25 years.18,19 While screening for human immunodeficiency virus occurs in all pregnancies, there is no current national guidance for routine chlamydia screening in pregnancy; however, screening those at risk (including those under the age of 30 years) in the first trimester is recommended.20 Early testing aims to prevent adverse effects such as intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth and stillbirth,21 whereas retesting during the third trimester (usually defined as week 27–40 of pregnancy) aims to prevent maternal postnatal complications such as endometritis21 and chlamydia infection in the neonate. Syphilis has had a resurgence in Australia,22 and in 2017, rates among women were highest in the 15–19-year age group (15.9 per 100,000).23 There were more than 44 congenital syphilis notifications between 2008 and 2017, and more than half of those were in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. Routine testing for syphilis is recommended at the first antenatal contact, with repeat testing recommended between 28 and 32 weeks and at the time of birth for women at high risk of infection or reinfection. In areas affected by the ongoing syphilis outbreak, testing is recommended at the first antenatal visit, at 28 and 36 weeks, at the time of birth and again six weeks after the birth.22

Smoking

Maternal tobacco smoking and second-hand smoke exposure during pregnancy are the leading preventable causes for a variety of unfavourable pregnancy outcomes. Teenage girls have a higher rate of smoking than older pregnant women during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy (32%, compared with 21%) and also later in pregnancy (25%, compared with 16%).24 Smoking in pregnancy increases the risk of miscarriage, low infant birthweight and preterm delivery.25 There is also increasing evidence for longer-term adverse health outcomes related to body mass index, with a recent meta-analysis finding that children of women who smoked during pregnancy had an increased risk of obesity in childhood when compared with children of women who did not smoke.26 Smoking cessation in early pregnancy can almost eliminate these risks.

It is recommended that smoking be addressed at every GP visit during pregnancy in view of its serious health impact. Although there is a dearth of evidence for the effectiveness of smoking cessation programs for teenagers,27 current programs and interventions may be beneficial. Behavioural counselling that includes providing information on the health effects, problem solving and facilitating social support and referral to Quitline is regarded as first-line treatment in pregnancy.28 The use of nicotine replacement therapy may increase cessation rates and is considered safer than continued smoking, with no adverse fetal effects.29 For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, government-funded nicotine replacement is available through the ‘Close the Gap’ scheme.

Another form of nicotine delivery is electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes, with ever use approximately 7% among young Australians aged 12–17 years.30 Although the aerosol of e-cigarettes generally has fewer harmful substances than cigarette smoke, e-cigarettes and other products containing nicotine are not regarded as safe to use during pregnancy. Further, there is insufficient evidence to know whether e-cigarettes help people to quit smoking.

Alcohol and other drugs

Young people are starting to drink at a later age,31 and teenagers who become pregnant are less likely to drink any alcohol before pregnancy when compared with women over the age of 20 years.32 They are also more likely to cease alcohol intake with recognition of pregnancy. However, asking about alcohol use is essential, as fetal alcohol spectrum disorder has lifelong consequences for the individual and their family and is extremely costly to the health, education, disability and justice systems.33 Screening for other drugs is also important, with data from the USA suggesting that a sixth of younger pregnant women use marijuana in pregnancy, with a significant association between drug use and a composite outcome of spontaneous preterm birth, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, stillbirth or small size for gestational age.34 Recognition of the use of these drugs requires enquiry about them. GPs are well placed to develop a trusting relationship that allows regular discussion about drug use with teenagers.

Complications of pregnancy

Maternal outcomes

Overall, pregnancy in the teenage years carries an increased risk of some medical and obstetric complications but a decreased risk of others. Recent studies suggest that the most commonly cited adverse outcomes of preterm birth and low birthweight may relate mainly to issues of sociodemographic disadvantage and substance use in pregnancy.35 Therefore, support from a multidisciplinary team – ideally including the GP, midwife, obstetrician and social work team – throughout pregnancy is vital.

Antenatal outcomes

In terms of antenatal care, teenage girls are less likely to have five or more antenatal visits (90%) than a comparative cohort aged 20–24 years24 and more often present later for care. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teenage girls attend even fewer antenatal appointments, with almost a tenth attending only one or two visits.24 Characteristics that encourage attendance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teenage girls are the presence of Aboriginal health workers or liaison officers, a continuous relationship with the care provider and support for attendance.36 Collaborative care models that involve the partners and other family members in the visits may be beneficial.

In the antenatal period, teenage girls have an increased risk of depression,37 iron deficiency anaemia38 and urinary tract infections, compared with adult women. They also have higher rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, compared with adult women.39 However, when compared with older mothers, teenagers have a decreased risk of gestational diabetes and venous thromboembolism.24,32,40

Perinatal outcomes

Most studies have found a two-fold increase in the incidence of preterm delivery (<37 weeks’ gestation) when compared with women aged 20–30 years, so providing education about the signs and symptoms of early labour is important.41 With regards to mode of delivery, teenage girls when compared with adult women are more likely to have a vaginal birth (69%, compared with 65%) and less likely to have a caesarean section (18%, compared with 23%).24

Neonatal outcomes

Infants born to teenage mothers are more likely to be preterm, have low birthweight and be small for gestational age.42 Additionally, there is a strong association between teenage births and increased perinatal mortality,43 neonatal mortality,43 child mortality44 and stillbirth. A recent Australian report on teenage mothers documented the rates of preterm birth and low birthweight among the babies of teenage mothers to be 11% and 8.9%, respectively; these figures were 9.9% and 7.6%, respectively, for mothers aged 20–24 years. These outcomes are worsened if the teenage mother is from a low socioeconomic or Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background. Similarly, stillbirth and neonatal death rates have also been found to be higher in babies born to Australian mothers aged <20 years compared with mothers aged 20–24 years: 13.9 in comparison to 7.8 stillbirths per 1000 births, and 4.3 in comparison to 2.9 neonatal deaths per 1000 live births.24 Pregnant teenagers need to be educated about the importance of fetal movements and what to do if there is a change in the pattern of fetal movements. It is important that healthcare practitioners understand these risks and monitor fetal development and maternal health more carefully in the third trimester, with consideration of extra assessments of fetal wellbeing including ultrasonography at 36 weeks’ gestation.

Postnatal care

One of the key issues in postnatal care is supporting breastfeeding, with qualitative studies suggesting that teenagers may not seek assistance with lactation difficulty.45 Teenage mothers may also need advice regarding a healthy diet, with a systematic review finding that intakes of energy, fibre and a number of key micronutrients were below recommended levels in this group.46 A struggle with mental health issues in the postpartum period is not uncommon among young mothers, who have a known elevated risk of postpartum depression,47 which can exacerbate the parenting difficulties they may experience. Connection to a GP and continuity of care is particularly helpful for young families, who benefit from continued non-judgemental and knowledgeable medical care.

Teenage mothers have an elevated risk of rapid repeated pregnancy within two years of their first pregnancy.48 Ideally, contraception should be provided in the immediate postpartum period before hospital discharge, using long-acting reversible contraception (LARC; ie implants and intrauterine devices) methods that have been shown to be the most effective at reducing future unintended pregnancy49 while having no impact on breastfeeding nor infant growth and development.50 Postnatal home visits from midwives can also improve contraception outcomes and should be encouraged.51 GPs have a crucial role in ensuring young women are informed about their contraceptive options prior to and after delivery, and in explaining the advantages of the LARC methods.

Long-term outcomes

Teenage pregnancy is a contributing factor to lifelong socioeconomic disadvantage and health disparities for the mother and her child.52 When compared with women who become pregnant during adulthood, teenage mothers are more likely to have limited social support, low educational attainment, fewer employment opportunities,40,53 poorer mental health37 and higher rates of substance use.37,54 There is a significant body of research showing an association between teenage motherhood and depression55 and anxiety.56 These factors can adversely affect parenting ability and have an impact on behavioural outcomes for their children.37

Preventing teenage pregnancy

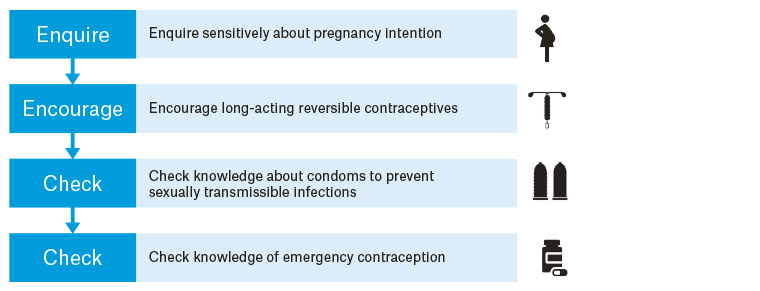

Addressing teen pregnancy prevention requires broad efforts that involve schools, health services and the community (Figure 3). Specifically, a combination of sexuality education and contraception interventions is effective in reducing unintended pregnancies in teenagers.57 Use of contraception at first intercourse has been reported by 90% of Australians, and condoms are the most common method used by young people; this is followed by the oral contraceptive pill, which is often initiated for non-contraceptive indications.58 However, inconsistent use of condoms and contraceptive pills leading to unintended pregnancy is common in teenagers, and they may benefit from use of the LARC methods. The CHOICE study in the USA showed that 70% of women who are given balanced advice about the range of contraceptive options and provided with free treatment chose LARC,59 but only 4% of Australian teenage girls use these methods.60 The GP has a key role in identifying teenagers who may be at risk of unintended pregnancy and sensitively enquiring about their plans for conception. At-risk groups include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teenage girls, disadvantaged or rural/remote residents, teenagers born to teenage mothers, those living in a home that is disrupted or abusive, those with a history of sexual abuse and those who have already had a child. Although many teenagers source their contraceptive methods from pharmacies and supermarkets, a presentation to a GP is an opportunity to provide information about condoms for STI prevention, LARC methods and emergency contraception should their method not be used or not be used consistently.60 The Family Planning Alliance of Australia provides training in intrauterine device and contraceptive implant insertion (http://familyplanningallianceaustralia.org.au/services).

Figure 3. The healthcare practitioner’s role in reducing teenage pregnancy

Conclusion

For some young women, a pregnancy in adolescence can have a transformative impact on changing unhealthy behaviours and relationships. However, for many, teenage pregnancy is accompanied by adverse perinatal outcomes and long-term social and educational consequences. The GP is ideally placed to foster a supportive health environment for these families by offering regular and reliable care in a non-judgemental approach. Evidence supports the use of LARC methods to prevent unwanted teenage pregnancy and to reduce rapid repeat pregnancy after delivery.