Background

Neck masses in adults are a common presentation for head and neck cancer. Head and neck cancer accounts for 3.4% of all malignancies in Australia, and the incidence of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma is rising. Early diagnosis is essential to prevent worsening prognosis.

Objective

This article provides a brief overview of neck masses in adults, with a guideline to work-up and management in a primary care setting.

Discussion

All neck masses should be considered malignant until proven otherwise. Detailed history and examination is crucial in the initial work-up. Fine-needle aspiration and computed tomography of the neck with contrast make up the mainstay of first-line investigation.

Neck masses are a common cause of presentation to general practitioners (GPs) and may be the only presenting complaint of a patient with head and neck malignancy.1 In adults, head and neck malignancy is the most common cause for neck masses,2,3 and it accounts for 3.4% of all malignancies in Australia.4 Delays in diagnosis of up to 180 days are not uncommon,5 with referral delay being associated with a three-fold increase in mortality.5 Given the incidence of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in Australia is rising,6–8 this should prompt the need for increased vigilance; early referral to a specialist ear, nose and throat (ENT) service is prudent if any concerns or uncertainty in management is encountered. For these reasons, all adult neck masses should be considered malignant until proven otherwise.9

The purpose of this article is to provide a systematic approach to the work-up of neck masses, including pertinent signs and symptoms, recommended investigations and when to refer for ENT specialist management.

Human papillomavirus

In recent years, the rates of human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive oropharyngeal cancer have risen markedly, with the prevalence more than tripling from 19% to 66% between 1987 and 2006.10,11 The overall rate of oropharyngeal cancer is increasing despite lower rates of tobacco use.6–8

When compared with HPV-negative oropharyngeal malignancy, patients with HPV-positive head and neck cancer often do not fit the stereotype for a patient with malignancy (Box 1), which results in a delayed cancer diagnosis.12

| Box 1. Features suggestive of human papillomavirus–positive oropharyngeal cancer24,25 |

- Younger age

- Male sex

- Higher number of oral and vaginal sexual partners

- Less or no tobacco exposure

- Less alcohol consumption

- Marijuana use

- Higher education

- Higher socioeconomic status

|

HPV-positive head and neck cancers are more likely to present with an asymptomatic neck mass,13 and the neck nodes are frequently cystic. These are often misdiagnosed as branchial cleft cysts,14 leading to delayed diagnosis and delayed treatment. Given the rise of HPV-related head and neck cancer, the possibility of an incorrect diagnosis must always be considered.

Initial assessment

Thorough history-taking is vital, and the presence of any red flag symptoms or risk factors should be documented.

Red flag symptoms for head and neck cancer include:9

- a mass that has been present for >2 weeks

- a recent voice change

- dysphagia or odynophagia

- ipsilateral otalgia, nasal obstruction or epistaxis

- unexplained weight loss or loss of appetite.

Risk factors for head and neck cancer include:9,15

- smoking

- alcohol use

- age >40 years

- past history of previous head and neck malignancy

- past history of head and neck cutaneous lesions.

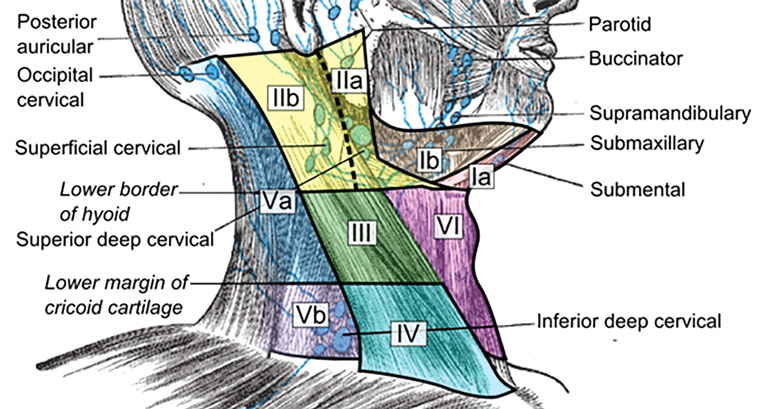

Assessing the location of a neck mass is essential as it provides clues to the aetiology. Emphasis should be placed on documenting the location accurately. The neck is divided into six levels, each describing a lymph node region, with the midline being the central dividing line between left and right (Figure 1):16,17

- Level I: the submental and submandibular triangles

- Level II, III, IV: the upper, middle and lower internal jugular chain

- Level V: the posterior triangle

- Level VI: the anterior compartment.

Figure 1. Anatomical diagram depicting the six levels of the neck

Further assessment should pay specific attention to characterising other features of the neck mass and completing a full head and neck examination.

Other features of the neck mass that require characterisation are:18

- mobility of the neck mass (fixed masses are more likely to be malignant)

- size (>1.5 cm is more likely to be malignant)

- firmness

- overlying skin ulceration.

Examination of the head and neck includes:

- inspection for cutaneous lesions

- otoscopy (unilateral middle ear effusion may indicate nasopharyngeal carcinoma)

- anterior rhinoscopy

- oral cavity inspection and palpation

- oropharyngeal inspection (looking for masses, ulceration)

- tonsil enlargement or asymmetry

- flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy.

Investigations

First-line investigations for all adults at risk of malignancy consist of computed tomography (CT) of the neck with contrast and fine-needle aspiration (FNA). These two investigations provide complementary information including primary tumour histopathological detection, anatomical localisation and nodal staging. Simultaneous arrangement of these investigations prevents delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Computed tomography of the neck with contrast

Contrast-enhanced CT of the neck should be considered a first-line investigation for all patients at increased risk of malignancy.19 This will assist in the localisation of the primary neoplasm, assess for further cervical lymphadenopathy and aid in the staging process. Furthermore, it may provide information that suggests a benign process rather than malignancy (eg salivary calculi, dental infection). Contrast should always be administered for enhanced soft-tissue differentiation unless a prior contraindication is present (eg iodine allergy, renal impairment).19 Although contrast-enhanced CT of the neck is considered a first-line investigation, studies have shown a negative predictive value of 0.33 for the detection of primary tumours and 0.57 for the detection of recurrent tumours in the head and neck.20 For this reason, patients with a suspicious neck mass and normal contrast-enhanced CT of the neck should always undergo further evaluation by an ENT specialist.

Fine-needle aspiration

FNA should be considered a first-line diagnostic test for all patients at increased risk of malignancy. It is safe and cost effective and has an overall accuracy of 93.1% (73.3–98.0%) according to a meta-analysis.21

In indeterminate cases, a repeat FNA or core biopsy may be performed. A meta-analysis showed that ultrasound-guided core biopsy was highly accurate (96% detection rate for malignancy) with low complication rates (1%).22

Other investigations

Ultrasonography

Diagnostic ultrasonography is not recommended as a first-line investigation in preference to cross-sectional imaging (eg contrast-enhanced CT or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) as it is highly operator dependent. While it is useful to assist in obtaining an image-guided aspiration sample, the lack of visualisation of deeper structures limits its usefulness as an investigation.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck with contrast

Although MRI provides better soft-tissue contrast,19 CT is the preferred primary imaging modality, as MRI demonstrates more motion artefact, longer scan times and generally poorer availability and tolerability.

Positron emission tomography with computed tomography

Positron emission tomography (PET) with CT using fluorodeoxyglucose tracer has shown excellent sensitivity and specificity in the assessment of primary and recurrent head and neck tumours.20 As such, PET/CT is playing an increasingly greater part in the work-up of head and neck tumours, especially in the detection of residual or recurrent tumours post-treatment.23 However, given its limited availability, PET/CT is not appropriate as a first-line imaging study.

Ancillary investigations

Ancillary tests are intended to assist clinicians when malignancy is unlikely or when initial investigations do not yield a diagnosis. If these tests are undertaken, they should be based on clinical suspicion for specific diseases and should be obtained simultaneously to the malignancy work-up to prevent a delayed diagnosis. Ancillary investigations are shown in Table 1.9

| Table 1. Ancillary investigations for adult neck masses |

| Ancillary investigation |

Rationale |

| Full blood examination |

Elevated white cell count may indicate infection or lymphoma |

| Anti-neutrophil antibody (ANA) |

Elevated ANA may indicate autoimmune diseases |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) |

Elevated ESR may indicate autoimmune diseases |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) |

TSH abnormalities may indicate thyroid pathology (eg multinodular goiter, Grave’s disease) |

| Parathyroid hormone (PTH) |

Elevated PTH may indicate parathyroid adenoma |

| Thyroid ultrasonography |

May reveal thyroid nodules, parathyroid adenomas |

| Computed tomography of the chest with contrast |

May reveal lung malignancy, tuberculosis or sarcoidosis |

| Specific infection tests (eg human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, tuberculosis) |

Positive tests may indicate infectious cause |

Investigation process

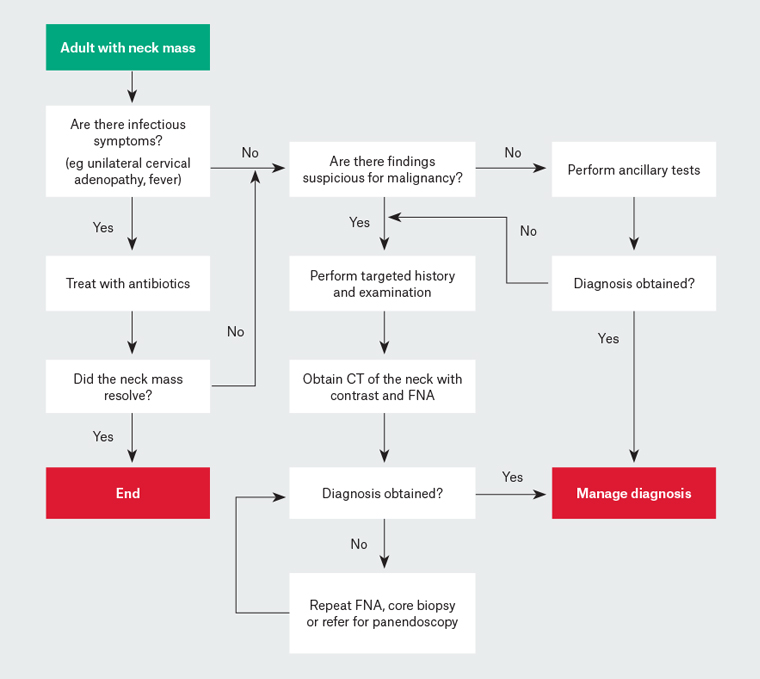

Investigation of neck masses relies on excluding malignancy. Deciding on the course of investigation depends on an assessment of signs and symptoms, and consideration of the results of previous investigations. At each stage of the investigative process, referral to a specialist ENT service should be considered to prevent referral delay. An approach to investigation is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Flowchart for work-up of adults with a neck mass9

CT, computed tomography; FNA, fine-needle aspiration

Key points

- Head and neck malignancy is the most common cause of adult neck masses.

- It is recommended that all adult neck masses be considered malignant until proven otherwise.

- All patients presenting with a neck mass should have a thorough history taken and examination performed followed by targeted investigations.

- It is important to continue investigations until a clear and specific diagnosis has been reached.

- CT of the neck with contrast and FNA are the mainstay of investigation for all patients with a neck mass suspicious for malignancy.

- Further evaluation by an ENT specialist is required for any patient with a suspicious neck mass and normal contrast-enhanced CT of the neck.

- Ancillary testing may be performed, without delaying investigation for malignancy.

- The advice of an ENT specialist can be sought if there are any concerns or uncertainties.