General practice training in Australia may not be as safe as it should be. In a recent Australian study that reviewed records of registrar consultations, patient safety concerns were identified by 30% of supervisors, with 16% of supervisors needing to subsequently contact the patient.1 These findings raised concerns that registrars may not be calling for supervision when they should.

Although The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ (RACGP’s) Standards for general practice training requires general practice registrars to be supervised to ensure they only manage patients they are competent to manage; however, these are outcome standards.2 A specific level of supervision is not mandated. In contrast, an international medical graduate starting out in practice in Australia is often expected to commence under Medical Board of Australia level 1 supervision, calling their supervisor about each patient before the patient leaves the facility.3 Doctors in general practice training in New Zealand, Ireland, Canada, The Netherlands and the UK all receive closer supervision than Australian general practice registrars.4

In an earlier phase of research into the management of high-risk consultations in early general practice training, these authors interviewed lead medical educators in each of the nine Regional Training Organisations (RTOs).5 It was found that RTOs are delegating the responsibility to ‘make sure the registrar is safe’ to training practices of acknowledged variable quality. The use of high-risk checklists by supervisors varies widely, and training practices are not routinely monitored to ensure registrars are appropriately supervised for high-risk encounters. Within a few weeks of commencing general practice training, a registrar is expected to be consulting under Medical Board of Australia level 3 supervision, only calling their supervisor when they consider it necessary.

In summary, compared with doctors in general practice training in other countries and doctors commencing general practice in Australia outside of the training program, there appears to be a greater onus on Australian general practice registrars to determine when a situation is high risk. No routine monitoring ensures that a registrar is consulting safely, and it may be that registrars are not calling for help when they should.

If Australian general practice training continues to commence without Medical Board of Australia level 1 supervision, can it be made safer? Is there a role for checklists or entrustable professional activities (EPAs)?

Checklists are well accepted as methods to contemporaneously reduce risk in healthcare.6,7 A safety checklist for general practice registrars has been developed in the UK for early general practice training but, given the differences in training environment, may not be useful in the Australian context.8 The RACGP’s Standards for general practice training include a list of areas (Box 1) that pose a high risk for doctor and patient.2 The use of this list, to these authors’ knowledge, has not been evaluated. Some items (eg intramuscular injections) appear unlikely to warrant supervision, whereas others (eg all children, all trauma) include many presentations that would not be high risk. Asking a registrar to call for ‘diagnosis of malignancies’ lacks the clarity needed for contemporaneous identification of a high-risk situation, compared with detailing the specific clinical presentations where supervision is expected.

| Box 1. High-risk areas in The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ current Standards for general practice training 2 |

- Diagnosis of malignancies

- Diagnosis of serious medical and/or life-threatening problems

- Diagnosis of serious surgical problems

- Assessment of trauma

- Diagnosis and assessment of children

- Medication misadventure – prescribing error, inappropriate medication, medication administration error, adverse medication reaction

- Privacy procedures

- Procedures including intramuscular injections, venepuncture, ear syringing, minor surgery, cryotherapy, implants and intrauterine device insertion

|

EPAs are a relatively new assessment tool conceived for use in clinical practice and have patient safety as a component of the assessment.9,10 They involve assessing a registrar’s ability to perform complex tasks by considering how much supervision is required to perform the task safely. There is concern that although entrustment is a familiar concept, assessments may not be reliable.11

The aim of the current study was to answer two questions: what are the high-risk situations in early Australian general practice training that require closer supervision, and how can closer supervision of these high-risk situations be best achieved?

Methods

The researchers chose to explore these questions using a qualitative approach and a social constructivist theoretical framework. A qualitative approach is best suited to explore the attitudes and beliefs of those involved.12 Social constructivism envisages collaboration to design environments that foster optimal learning.13

The research team consisted of a general practice supervisor and medical educator (GI), a general practice registrar and medical educator (KP), a PhD research academic with experience in qualitative research (RK), and an RTO administrator (NW). Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (project 12673).

An action research model was adopted.14 In action research, researchers work with participants through multiple cycles (or spirals) involving action, observation, analysis and modified action. The research questions, methods and outcomes are concurrently and continuously refined. The research team chose focus groups as the best method of investigation for this project. Focus groups allowed for expert–group interaction and discussion in the iterative development of the list and guidelines for its implementation. Focus groups are more efficient than individual interviews in terms of both time and synergy, and provide important insights on the degree to which participants agree or disagree with each other and why.15

There were 75 participants across seven focus groups. Four focus groups comprised general practice supervisors, who were well placed to answer the research questions as they are immersed in this issue in their daily work. Two focus groups comprised general practice registrars who had recently completed their first term of training and were considered best able to recall the challenges of early general practice training. The final focus group included general practice supervisors also employed by RTOs to work as medical educators (henceforth referred to as GPSME) to deliver training and assessment. The opinions and views of this group were pursued for their expertise in registrar assessment and RTO systems combined with practical in-practice training knowledge. The number of participants in each focus group and their order are provided in Table 1.

| Table 1. Details of focus groups |

| Focus group number |

Number of participants |

Type of participants |

| 1 |

6 |

Registrars |

| 2 |

31 |

Supervisors |

| 3 |

8 |

Supervisors |

| 4 |

3 |

Supervisors |

| 5 |

15 |

Supervisors |

| 6 |

6 |

Registrars |

| 7 |

6 |

Supervisors who also work as medical educators |

General practice supervisors were recruited from attendees of supervisor education workshops in Victoria and Tasmania, and general practice registrars were recruited from attendees of registrar education sessions in Victoria. Both groups were purposively sampled to include rural and urban participants. GPSME members were recruited using a snowballing technique from four participants originally identified by the researchers.

The general practice registrar and supervisor groups were conducted face to face, and the GPSME focus group was undertaken via web conference. All meetings lasted approximately 90 minutes and were recorded and transcribed. Other data available for analysis were the high-risk lists created and ranked by the focus groups.

Prior to the first focus group, a compilation of existing lists of high-risk activities and an understanding of the options for closer supervision was sought through a literature review and from the interviews of lead medical educators in an earlier phase of the research project.4 The outcomes of the literature review and interviews were presented to the first focus group.

Each focus group met only once and commenced with a summary of the progress of the research to that time. Next, participants were asked to record 10 items that should belong on a general practice registrar safety checklist. The items were discussed and modified by the group. The list from the previous focus group was then revealed and considered and combined with the current group’s own list, then edited by the group to produce a final list for that focus group. Items on this list were ranked by group members for importance to remain on the list. Finally, the focus group was asked how they thought the list could be used in practice.

Although all groups were asked to consider both research questions, earlier groups focused on developing the list and the later groups spent more time editing the list and considering implementation.

Between each focus group session, the research team met to analyse the outcomes to that point and to review the list. In developing the list, the research team allowed addition of items until saturation was achieved. Items were only removed by the researchers from the list if they were ranked as unimportant by both registrar and supervisor focus groups. A classification was developed by KP and, with minor modification, accepted by the remaining research team members before being submitted to subsequent focus groups. In determining how the list should be used in practice, the research team first reached consensus on their understanding of the recommendations of the most recent group and any differing opinions within the focus group. Issues emerging from this understanding were then put to subsequent focus groups for clarification and ongoing iterative development by the participants of an approach to using the list in practice.

The GPSME group, which was the final group, was emailed the research outcomes after their meeting to obtain respondent validation and aid interpretative rigour. There was agreement that the results reflected the final focus group determinations.

Results

The following sections outline the list, list classification, using the list in practice, and potential problems or benefits. As the research involved multiple iterations, relevant concurrent analysis has been included with the results to assist the reader to make sense of the outcomes.

‘Call for help’ list

Eighty items were identified as situations that should trigger a registrar to call their supervisor (Tables 2 and 3). By the fifth focus group, no significant new items were being identified, indicating the achievement of ‘saturation’. There was agreement in the ranking of items on the list other than ‘heartsink patients’, which were considered relevant by registrars but not supervisors.

While most participants agreed the list is larger than ideal, there was no consensus on either a size limit for the list or a determining factor for list inclusion or exclusion.

It does look long, but there’s not much that you can take off. (General practice registrar, Group 6)

The researchers originally planned to keep the list small by asking participants to include only high-risk scenarios in which a registrar may not realise that they should call for help. However, participants from each of the groups rejected this approach. They wanted to retain high-risk scenarios on the list even if a registrar would be expected to call. They also included clinical scenarios that were not high risk, and broad triggers to encourage a registrar to call when uncertain.

I think having something that’s kind of agreed upon widely as a starter is actually beneficial for safety. (General practice registrar, Group 1)

Classification

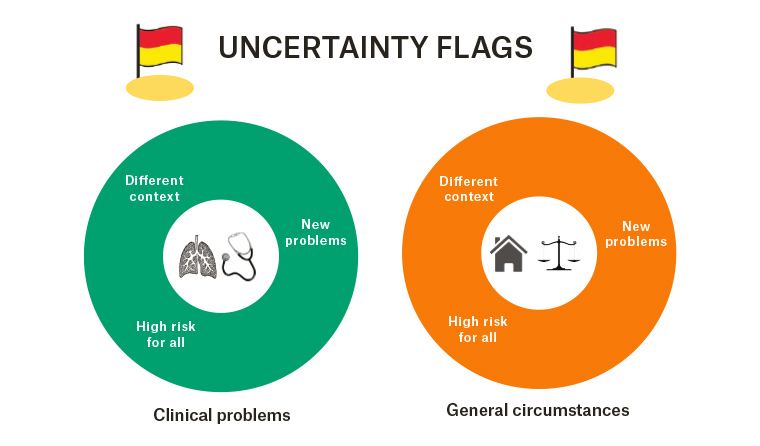

During analysis, the researchers noted that 10 items proposed for the list were broad indications of registrar uncertainty and not tied to a specific scenario. These were termed by the research team as ‘uncertainty flags’ (Box 2). The remaining 70 items were classified by both the circumstance requiring supervision and the justification for inclusion of the item on the list. When considering circumstances in which a call for help is indicated, the list was divided into clinical problems (Table 2) and general circumstances (Table 3). When considering justification for inclusion on the list, three reasons were identified: high risk for all, new problems and different context (Table 4). The classification of the list is illustrated in Figure 1.

| Box 2. Uncertainty flags |

- If you are considering sending a patient to the emergency department

- If you are unsure about sending a patient home

- If a patient presents for the third time for the same issue without a clear diagnosis or plan

- If you think you have made an error

- If you think there is going to be a complaint (disgruntled or dissatisfied patient or relative)

- When you are unsure to whom a patient should be referred

- If pathology or imaging results are abnormal beyond your knowledge

- When prescribing medications you are unfamiliar with

- ‘Heartsink’ patients (ie patients you are finding overwhelming)

- When a patient attends asking you for a ‘second opinion’

|

| Table 2. ‘Call for help’ list: Clinical problems |

| Clinical problem |

Justification for inclusion |

| Emergency medicine/Acute presentations |

| Acute significant systemic symptoms: collapse, rigors |

HR |

| Extreme abnormalities of vital signs |

HR |

| Acute onset of shortness of breath |

HR |

| Severe abdominal pain |

HR |

| Chest pain |

HR |

| Severe headache that is either new, sudden onset, associated with vision change or meningism |

HR |

| Concussion/post–head trauma |

DC |

| Trauma with high risk of injury (eg high-speed or rollover motor vehicle accident) |

HR |

| Post collapse, possible seizure |

DC |

| Acute eye issue – unilateral red, painful, vision loss or periorbital swelling |

DC |

| Sudden loss of hearing not due to wax |

DC |

| Fracture |

DC |

| Nerve, tendon or serious muscular injury |

DC |

| Acute red swollen joint |

DC |

| Possible malignancy |

| New bowel symptoms in a patient aged >50 years |

DC |

| Painless haematuria |

DC |

| Lymph node enlargement without simple explanation |

NP |

| Unexplained weight loss |

DC |

| PR bleeding |

DC |

| Testicular lump |

NP |

| A new or enlarging lump |

NP |

| Iron deficiency |

DC |

| Skin lesions, if you are unsure of diagnosis and whether to excise |

NP |

| Breast lump |

DC |

| Persistent cough |

DC |

| Mental health |

| Acutely suicidal patient |

HR |

| Acute psychosis |

HR |

| Paediatrics |

| All neonates |

NP |

| Six-week baby check |

NP |

| Australian immunisation schedule immunisations (including catch-ups) |

NP |

| Unwell child under two years of age |

DC |

| Failure to thrive under 12 months of age |

NP |

| Developmental delay |

NP |

| Child and adolescent mental health consultations |

NP |

| Child abuse or unexplained injury |

HR |

| Eating disorder |

NP |

| Women’s health |

| Antenatal consultations |

NP |

| Irregular vaginal bleeding |

NP |

| Postmenopausal bleeding |

DC |

| Postnatal depression |

NP |

| Cervical screening |

NP |

| Aged and palliative care |

| Dementia or delirium (acute cognitive decline) |

DC |

| Deciding whether to start or stop anticoagulation in elderly |

DC |

| Palliative care |

DC |

| Elderly patient not coping at home |

DC |

| Elderly patient with multimorbidity recently discharged from hospital |

NP |

| General medicine |

| Poorly controlled diabetes |

DC |

| Pyrexia of unknown origin |

DC |

| New neurological symptoms or signs |

DC |

| Severe exacerbation of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

DC |

| Rash you are unfamiliar with |

NP |

| Domestic (intimate partner) violence |

HR |

| Dependence/Addiction/Pain management |

| Chronic pain management |

NP |

| Managing alcohol/drug dependence |

DC |

| Sexual health |

| Patient requesting sexually transmissible infection screen |

NP |

| Travel medicine |

| Pre-travel consultations |

NP |

| Unwell returned travellers or international visitors |

DC |

| DC, general practice is a ‘different context’; HR, ‘high-risk’ situation for all general practitioners; NP, ‘new problem’ for most registrars; PR, per rectum |

| Table 3. ‘Call for help’ list: General circumstances |

| General circumstances |

Justification for inclusion |

| New or challenging consultations |

| Nursing home visits |

NP |

| Home visits |

NP |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander patient |

DC |

| Procedures being done for the first time in the clinic (eg excisions, implants, joint injections) |

NP |

| Making a new major diagnosis (eg cancer, diabetes, ischaemic heart disease) and starting management |

DC |

| Breaking bad news to patient (eg cancer, human immunodeficiency virus, adverse pregnancy outcome) |

DC |

| Pre-operative assessment of fitness for anaesthetic |

DC |

| Professional or legal |

| Certifying competency to sign a will or other legal documents |

NP |

| Workers’ compensation consultations |

NP |

| Driving assessment |

NP |

| Consultations involving determining whether someone is a ‘mature minor’ |

NP |

| Commencing a drug of dependence (S8) other than for palliative care |

DC |

| Repeat drug of dependence (S8) prescriptions |

NP |

| DC, general practice is a ‘different context’; HR, ‘high-risk’ situation for all general practitioners; NP, ‘new problem’ for most registrars |

| Table 4. Classification by reason for inclusion in the ‘call for help’ list |

| New problem |

A circumstance that a general practice registrar is unlikely to have encountered during previous standard prevocational training hospital terms. |

| Different context |

A circumstance that a general practice registrar is likely to have encountered during previous hospital training, but the general practice context makes diagnosis or management significantly different. |

| High risk for all |

A circumstance that is high risk for all general practitioners (GPs) and their patients. All GPs are likely to consider calling a colleague for an opinion. |

Figure 1. Classification categories of the ‘call for help’ list

Use of the list

Participants noted that registrars arrive in general practice with varied competencies. To reflect this, the list should be editable in response to the registrar’s clinical experience and skills.

This process of individualising would make it much more valid and a much shorter list for the particular registrar. (GPSME, Group 7)

This review of the list, potentially allowing removal of items, should occur early in the registrar’s term. Any modification of the list needs to be done cautiously, as hospital clinical experience in a specific area may not translate to competence in a general practice environment. For example, a hospital doctor’s experience of antenatal care may not include the early pregnancy management that occurs in general practice. The practice context also needs consideration when modifying the list. Where a practice has a special interest or serves a particular patient population, items may need to be added to the list.

Participants agreed that during the term the list should be the supervisor’s responsibility to monitor and adjust, but the registrar’s responsibility to maintain.

I think the registrar holding it takes some of the burden away from the supervisor. (GPSME, Group 7)

The registrar should call their supervisor for each item on the list until the supervisor determines that this is no longer necessary. The assessment that a registrar is no longer expected to seek supervision for an item on the list is made by their supervisor. This would be either through supervision of registrar clinical work, or by the issue being satisfactorily covered during an in-practice teaching session. It is likely that many items will remain on the list throughout the term, particularly the uncertainty flags and those that relate to situations that are high risk for all doctors.

I think to actually tick it off properly, we have to discuss with a supervisor and have the supervisor go through all the red flags and make sure that we understand them. (General practice registrar, Group 6)

Concerns and benefits

All participants were keen to avoid the list becoming a burdensome responsibility. The general practice registrar and supervisor groups did not consider it necessary to document the justification for removal of an item from the list.

That’s the issue when you talk about assessment. When it becomes a burden, it’s not achieving anything. (General practice supervisor, Group 4)

Removal of items from the list can occur when reflection is possible during teaching or feedback sessions and should not interrupt clinical workflow.

Participants indicated the list should be used as a supervision adjunct rather than as an assessment task. The GPSME group considered it likely that RTOs may have a contrary view and will want the justification for decisions documented, and the list, or parts of it, used for assessment purposes. They were concerned that this may reduce its value.

I think the more bureaucratic processes are put in it, the more resistance you get from, particularly supervisors, and the less likely it is to be implemented in a meaningful way. (GPSME, Group 7)

Most participants considered the list a useful aid to teaching and supervision and valuable to ensure patient safety.

What I like about the list is the fact that you can discover if there was some problem, rather than discovering it six months later. (General practice supervisor, Group 3)

Many supervisors were keen to use the list while it was still in development. The value of the list for planning learning and generating topics for clinical teaching sessions was frequently acknowledged. A few supervisors were concerned that a list perpetuated ‘hand-holding’ of junior doctors and might result in further delaying their clinical independence.

Discussion

Through action research, a list of circumstances in which a general practice registrar should seek supervision has been identified. Although the original intent was to focus on high-risk encounters and patient safety, the research outcomes include circumstances that are not high risk, as well as broad prompts for the registrar to call for help. Producing an outcome contrary to the planned research direction is not unexpected in action research and consistent with a social constructivist framework, which accepts the validity of knowledge that emerges from a collaborative process among stakeholders.13 The list reflects items that those in the training environment consider useful. Consequently, the authors have called the developed list a ‘call for help’ list rather than a high-risk checklist.

There was participant and researcher concern that the size of the list may affect its usefulness. Expecting a smaller checklist is perhaps unrealistic given the known breadth of problems encountered by general practice registrars in clinical practice.16 The authors have recognised the need for the list to be modified contextually for the registrar and practice, and this is likely to result in use of a smaller list. While the authors caution against an increase in items that can occur through ‘topic creep’,17 a limitation of the developed list is that was developed without input from those supervising in remote practice or Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander communities.

The classifications identified have complementary utility. ‘Uncertainty flags’ will encourage the registrar to call when they feel unsafe or unsure and will facilitate learning about dealing with uncertainty in general practice. Classification by circumstances in which a registrar should call for help is needed for easier recognition of the need for supervision during daily clinical practice. The classification by justification for inclusion in the list will be useful when a supervisor contemplates removing items from the list. It will encourage caution before removing items classified as ‘high risk for all GPs’ and promote consideration of the impact of the general practice environment on required skills and knowledge when removing items classified as ‘different context’.

The participants and researchers constructed a practical process for use of the list that facilitates supervision while minimising the training burden. Like EPAs, decisions to remove an item from the list will involve an assessment of the registrar’s ability to act independently, and full entrustment may not be achieved during the training term.9,18 However, there was rejection of the need to document the reasons for entrustment decisions, which is required in EPAs. Although expressed in the language of supervision, EPAs are fundamentally an assessment tool. Supervisor and registrar participants in the current study wanted an aid to supervision rather than an additional assessment requirement.

The supervisor and registrar rejection of increasing assessment burden was thought to likely conflict with medical educators, who may want ‘call for help’ checklist items to form part of programmatic assessment. Programmatic assessment involves multiple assessments during training, in contrast with a small number of high-stakes end-of-training assessments.19 On face value, it would appear reasonable to deal with this tension by creating fewer and more general checklist items, but this reduces the value of the checklist as a supervision tool. For example, a smaller Canadian list of 35 EPAs for family medicine20 and a South Australian list of 13 EPAs21 have broad assessments such as ‘care of an adult with a chronic condition’. Dutch supervisors and registrars found difficulties with implementing EPAs in primary care that are ‘formulated in general terms and therefore explain very little’.22

If the ‘call for help’ list is to be used in programmatic assessment, then, rather than reducing the list by creating umbrella terms, the authors propose careful selection of a limited number of items from the list to be developed into EPAs, leaving the remainder solely as aids to supervision. The clinical scenarios classified as new problems in general practice appear to be most suited for development into EPAs. To do this would involve providing a detailed description of the EPA; the knowledge, skills and attitudes required; the information required to assess progress; and the basis for formal entrustment decisions.9

Checklists are appealingly simple, but supervision in early general practice training is a complex task.23 Using the list will not resolve the concerning gap between Australia and comparable countries in the closeness of supervision at the start of general practice training. It would be dangerous for a registrar to conclude they should only call for help for circumstances present on the list and must independently manage all others.

In seminal work on supervision in general practice training, Wearne et al identified the importance of an ‘educational alliance’ between registrar and supervisor.24 Fundamental to the alliance is the general practice supervisor crafting the appropriate level of support for the clinical challenges the registrar encounters to create a ‘zone of optimal development’. In a recently developed measure of the supervisor–registrar relationship, supervisor support and safety were noted to be central to the alliance.25

The authors believe the ‘call for help’ list will aid the construction of this appropriate supervision environment. The conversation about items on the list at the start of training and throughout the training term will clarify the registrar’s current competence and the supervisor’s expectation about when supervision should be sought. Without this explicit conversation, the registrar may perceive pressure or experience a cultural expectation to act independently.26 Environments in which the extent of expected independent practice is unclear have been associated with negative patient outcomes.27

Another component of the educational alliance is the general practice supervisor’s involvement in the registrar’s educational development during the term. This process has been described as a dance in which the supervisor should take the first step.28 Participants in the current study recognised the value of the ‘call for help’ list in identifying topics for registrar learning. Within the dance analogy, the conversation between registrar and supervisor is the establishment of the dance card for the term.

The authors hope the ‘call for help’ list may find a place as a supervision tool complementing direct observation of consultations and audit methods such as random case analysis. It should be an aid to communication between registrar and supervisor, particularly regarding the registrar’s current competence and the supervisor’s willingness to help.

Implications for general practice

- The known: In early general practice training in Australia, a general practice supervisor is not required to review every patient seen by their general practice registrars. There are concerns that this level of supervision may be inadequate to ensure patient safety.

- The new: A co-designed ‘call for help’ checklist comprising 80 items for which a registrar should seek supervision until the supervisor determines this is no longer needed.

- Implications: The findings of this study outline a practical approach to improve both patient safety and the supervisor–registrar alliance.