Osteoarthritis affects approximately 2.2 million Australians (9.3%), causing pain, disability and reduced quality of life.1 The incidence of hip and knee osteoarthritis is increasing, and while non-operative management should be commenced initially and is successful for many patients, surgical intervention is recommended for advancing disease when other treatments have failed.2–5

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are cost-effective procedures that reliably improve pain, mobility and quality of life for most patients with end-stage hip and knee osteoarthritis.6 In 2018, >39,000 THA and >56,000 TKA procedures were performed in Australia, an increase of 125% and 156%, respectively, over the past 15 years.7 The incidence of THA and TKA is projected to increase by 208% and 276%, respectively, by 2030.8

Despite their success, THA and TKA are major operations that carry significant risks, including infection, implant loosening, fracture and other complications that may require revision surgery. Although 30-day mortality after THA and TKA has declined over the past 15 years, death remains a risk, especially in older patients.9 Recent literature has identified a number of modifiable risk factors (MRFs) that increase the risk of these complications.10–12 These MRFs include obesity, diabetes, tobacco use, opioid use, anaemia, malnutrition, poor dentition and vitamin D deficiency (Table 1). There is a growing body of evidence that pre-operatively correcting these MRFs can reduce the incidence of post-operative complications.13,14

In addition to addressing MRFs, post-operative outcomes can be improved with prehabilitiation, focusing on patient education and exercise.15

The aim of this article is to discuss MRFs and prehabilitation to minimise risks and improve patient outcomes following THA and TKA.

| Table 1. Summary of recommendations for modifiable risk factors |

| Modifiable risk factor |

Recommendations |

| Obesity |

Aim for a body mass index <40 kg/m2 prior to arthroplasty. |

| Diabetes mellitus |

Aim for a glycated haemoglobin of ≤53 mmol/mol (≤7%) prior to arthroplasty. |

| Tobacco use |

Aim for smoking cessation at least four weeks prior to arthroplasty. |

| Opioid use |

The use of opioids for osteoarthritis should be avoided. |

| Anaemia |

Haemoglobin should be routinely checked prior to arthroplasty.

Anaemia should be corrected pre-operatively. |

| Malnutrition |

Consider checking serum albumin prior to arthroplasty.

For patients with serum albumin <3.5 g/dL, consider referral to a dietitian pre-operatively. |

| Poor dentition |

Patients with poor dentition should undergo a dental review prior to arthroplasty. |

| Vitamin D deficiency |

Consider checking serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) prior to arthroplasty.

For patients with low serum 25OHD, consider providing supplementation pre-operatively. |

Obesity

Two-thirds of Australian adults have a high body mass index (BMI), with 31.3% considered obese.1 The incidence of obesity has increased from 18.7% since 1995. In Australia, >40% of THA and almost 60% of TKA are performed on patients with obesity.7

Recent systematic reviews have shown an increased risk of superficial and deep infections, dislocations, reoperations, revisions and readmissions in patients with obesity undergoing THA when comparted with non-obese patients.16–18 Similar studies have found that the risk of revision for infection is higher in patients with obesity undergoing TKA when compared with non-obese patients.19,20

The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) recommends delaying THA and TKA for patients with a BMI of ≥40 kg/m2 to allow time for weight loss.21

Diabetes

Approximately 1.2 million Australians live with diabetes, accounting for almost 5% of the population.1

Patients with diabetes are at higher risk of experiencing complications and poorer functional outcomes after arthroplasty when compared with non-diabetic patients.22,23 However, glycaemic control appears to be an important factor. In a study of more than one million joint replacements in the USA, patients with uncontrolled diabetes were shown to have an increased risk of post-operative cerebrovascular accident (CVA), urinary tract infection, ileus, haemorrhage, transfusion, wound infection and death.24

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ (RACGP’s) guidelines for management of type 2 diabetes recommend a target glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) of ≤53 mmol/mol (≤7%).25 This target should be achieved prior to arthroplasty, as an HbA1c >61 mmol/mol (>7.7%) has been shown to increase the risk of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI).26

Tobacco use

Although the incidence of smoking has decreased significantly, approximately 2.6 million adults in Australia (13.8%) still smoke tobacco daily.1 Smoking increases the risk of post-operative pneumonia, CVA, PJI, revision and one-year mortality following THA and TKA.27–29 Patients who are ex-smokers are at lower risk of these complications than patients who currently smoke, but their risk is still higher than that of patients who have never smoked.29 Smoking cessation interventions, even four weeks prior to surgery, have been shown to reduce post-operative complications.30 The RACGP has published evidence-based recommendations for pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions to support smoking cessation.31

Opioid use

It is estimated that 1.5% of Australians take opioid medication daily.32 There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that pre-operative opioid use worsens outcomes after THA and TKA. Studies have shown longer length of stay (LOS), lower patient-reported outcome measures, prolonged post-operative opioid use and higher revision rates in this patient group.12,33–35 The RACGP strongly recommends against the use of oral or transdermal opioids in the management of patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis.4

Anaemia

Anaemia is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a haemoglobin level <120 g/L in non-pregnant women and <130 g/L in men.36 In Australia, approximately 4.5% of adults are at risk of anaemia; however, this increases to 16% in those aged >75 years.37

A number of studies have shown that pre-operative anaemia is associated with an increased risk of PJI, longer LOS, allogeneic transfusion and cardiovascular complications after THA and TKA.38,39 Identifying and treating anaemia is recommended prior to arthroplasty. Oral iron supplementation is an effective treatment modality for patients with anaemia on arthroplasty waiting lists.40 Intravenous iron transfusion should be considered for patients who do not respond to oral supplementation or for whom delaying surgery is unsafe.41

Malnutrition

Malnutrition is common in patients undergoing THA and TKA.42 Paradoxically, a large proportion of malnourished patients undergoing arthroplasty are obese.43 Malnutrition has been shown to increase the risk of medical and surgical complications following arthroplasty, including PJI, revision surgery and 90-day mortality.44

Serum albumin <3.5 g/dL is indicative of malnutrition.44 Other biochemical markers include total lymphocyte count <1500 cells/mm3 and transferrin <200 mg/dL.42 Baseline blood tests should be ordered pre-operatively, and at-risk patients referred to a dietitian prior to surgery.

Poor dentition

In Australia, almost 13% of adults have decayed, missing or filled teeth as a result of dental caries. The prevalence of moderate or severe periodontal disease is nearly 23%.45 Poor dentition is associated with an increased risk of PJI.11 For patients with poor dentition, a pre-operative dental review is recommended.

Vitamin D deficiency

It is estimated that 31% of Australian adults are vitamin D deficient, with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) levels <50 nmol/L.46 Studies suggest that there may be a link between vitamin D deficiency and risk of PJI and poorer patient-reported outcome measures post-arthroplasty.47,48 Pre-operative supplementation for patients with vitamin D deficiency may be beneficial.

Prehabilitation

Pre-operative patient education is vital to set appropriate expectations and ensure patient engagement with the treatment process. Similarly, pre-operative cardiovascular exercise and joint strengthening exercises are important to maximise post-operative recovery. A recent meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials showed that prehabilitation, including education and exercise, improved outcomes after THA and TKA.15 For THA, patients who underwent prehabilitation had less post-operative pain, improved post-operative function and shorter LOS. For TKA, patients who underwent prehabilitation had improved post-operative function, greater quadriceps strength and shorter LOS.

Many health services provide prehabilitation programs for patients undergoing arthroplasty. In the absence of such programs, pre-operative referral to a musculoskeletal physiotherapist should be considered.

Conclusion

THA and TKA offer longstanding improvement in pain, function and quality of life for patients with end-stage hip and knee osteoarthritis when non-operative treatments have failed. Patient optimisation prior to surgery is important to minimise risks and maximise recovery.

Obesity, diabetes, tobacco use, opioid use, anaemia, malnutrition, poor dentition and vitamin D deficiency have all been identified as MRFs that should be addressed prior to arthroplasty. Several studies have shown improvements in short-term outcomes when MRFs are addressed, including shorter LOS, fewer emergency department visits, and lower 30-day and 90-day readmission rates.13,14,49 Prehabilitation, in the form of education and exercise, is also important to maximise outcomes after THA and TKA. Further research is needed to determine the optimal timing of pre-operative intervention and to assess the longer-term effects of addressing MRFs.

Case

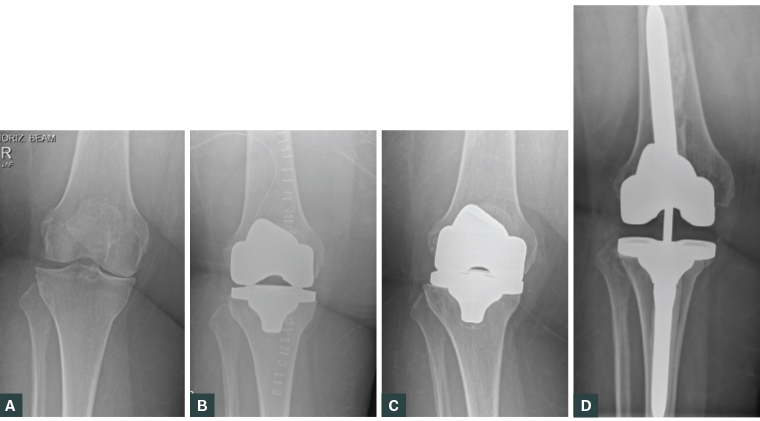

A woman aged 62 years presented with symptomatic medial compartment osteoarthritis of the right knee (Figure 1A). Her medical comorbidities included morbid obesity (BMI 52.5 kg/m2), obstructive sleep apnoea, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and hypothyroidism. She had undergone a successful left TKA five years prior.

The patient underwent a right TKA and made an uneventful recovery (Figure 1B). At her six-week and three-month post-operative reviews, she described satisfactory improvement in pain and function. Following her three-month review, she began experiencing gradually worsening pain in her right knee, and X-rays taken at her 12-month review showed loosening of the tibial baseplate (Figure 1C).

There was no evidence of infection clinically, and her serum inflammatory markers were low. The patient underwent a revision right TKA (Figure 1D). At the time of the revision surgery, her BMI was 54.2 kg/m2. Multiple tissue specimens taken intra-operatively were all culture negative. She made an uneventful recovery and remained symptom free four years later.

Figure 1. Anteroposterior knee X-rays from a female patient aged 62 years who underwent total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for symptomatic medial compartment osteoarthritis

A. Pre-operative X-ray demonstrating medial compartment osteoarthritis. Note the large soft tissue envelope; B. Immediate post-operative X-ray demonstrating satisfactory alignment of the primary TKA. Note the drain tube and surgical staples in situ; C. X-ray at the 12-month review. Note the collapse of the medial tibial metaphyseal bone and the varus angulation of the tibial baseplate when compared with Figure 1B; D. X-ray of the revision TKA, taken six months post-operatively. Note the long cemented femoral and tibial stems.

The key learning points of this case study include the following:

- Aseptic loosening of the tibial baseplate generally requires revision surgery.

- Morbid obesity has been linked to aseptic tibial baseplate loosening.50

- Revision arthroplasty carries a significant psychosocial burden to the patient and a large economic cost to the healthcare system.

- On the basis of AAOS guidelines, this patient’s TKA should have been delayed until her BMI was <40 kg/m2.21

- Non-operative management should have been optimised.5

- Strategies for weight loss should have been explored.